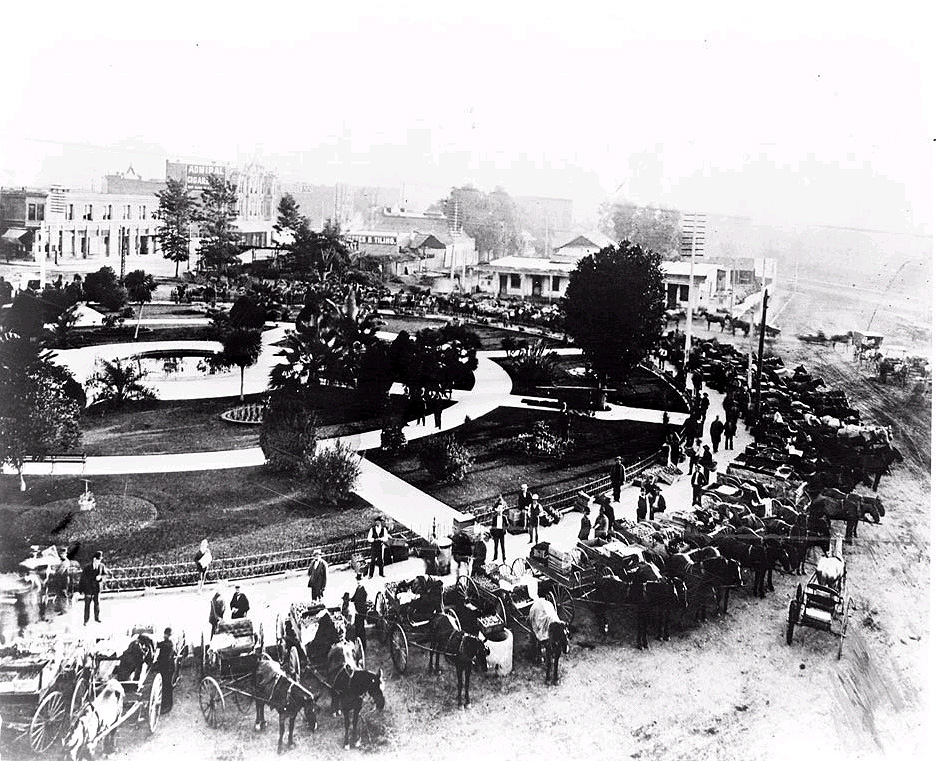

Early Los Angeles was pretty much the wild and woolly West, and it remained that way for a considerable period of time during the late 1800’s. In 1895, Los Angeles was significantly smaller than both San Francisco and Oakland in population size, totaling around seventy-five thousand people spread throughout the Greater Los Angeles area. To be more a little more specific, in 1895 “Los Angeles” was nicknamed “Angel City”. Los Angeles was not free from the national economic depression, caused by the Panic of 1893 which spread Westward, creating a greater fear in agrarian based economies that had collapsed all over the world. This period prompted the beginning of the “Free Silver” movement all over the nation.

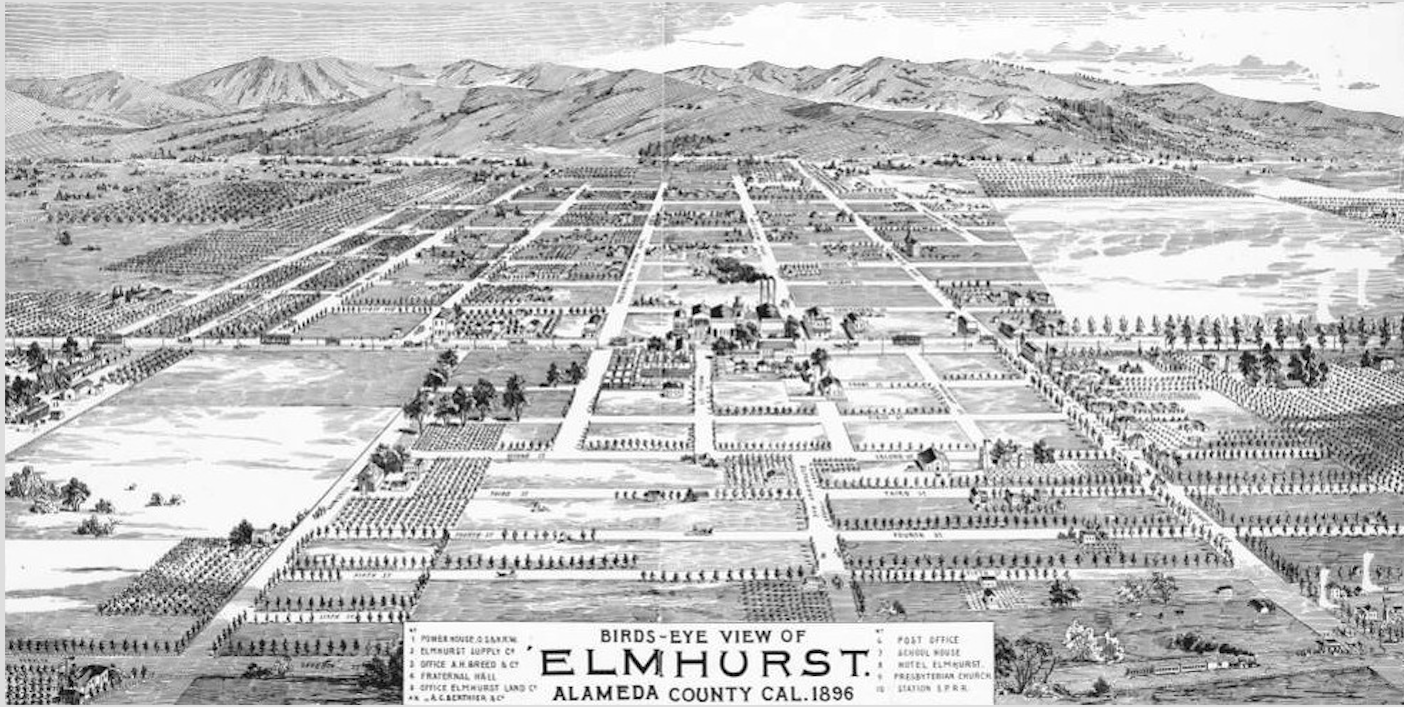

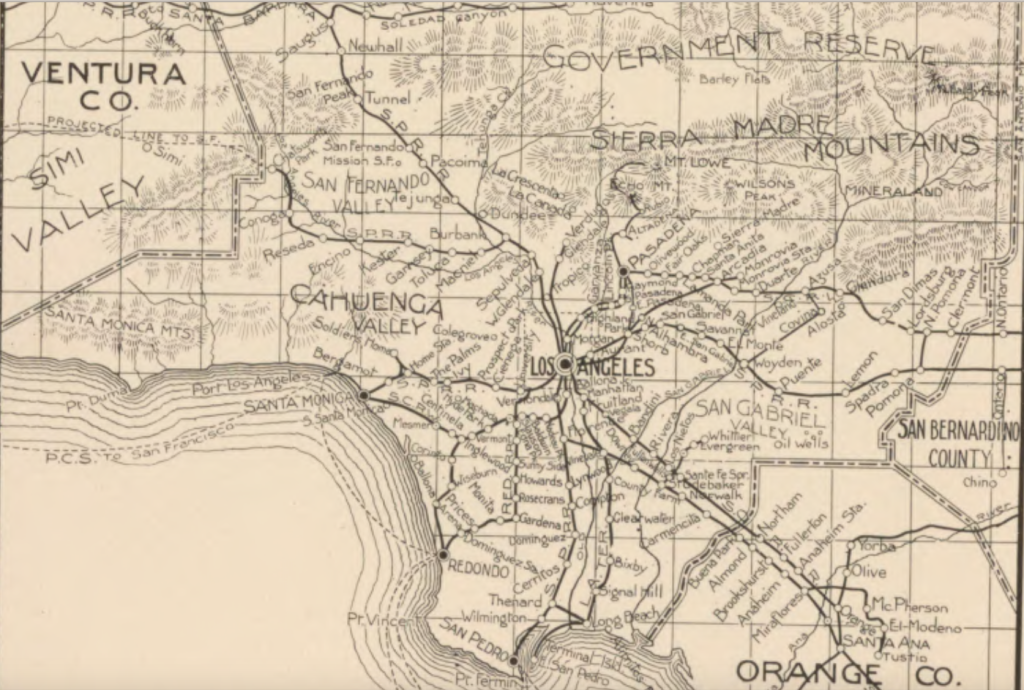

Charles F. Lummis walked from Ohio to Los Angeles, in 1884, and a little over a decade later — he published a magazine promoting Los Angeles as “The Land Of Sunshine“: The city itself sat directly in the center of the a series of valleys, mountains and peat fields — that stretched from Simi Valley to the San Gabriel Valley, surrounded by a series of “Ranchos” in the Los Angeles flat lands, — where many towns that exist today had not yet been incorporated into cities of their own, as extensions of modern day Los Angeles.

“Rancho Los Feliz”, “Rancho San Rafael”, “Rancho Pasqual Pasadena”, and “Rancho Santa Anita” all sat to the North of Los Angeles. “Rancho Francisquito”, “Rancho Potrero Grande”, “Rancho Potrero de Felipe Lugo”, and “Rancho Merced” all sat to the East of Los Angeles. “Rancho San Antonio” sat to the South East of Los Angeles. “Rancho Tajuata” and “Rancho San Pedro” sat to the South of Los Angeles. “Rancho Sausal Redondo”, “Rancho Aguaje de la Centinela”, “Rancho la Ballona”, “Rancho Cienega O’Paso de la Tijera”, “Rancho Las Cienegas” and “Rancho La Brea” sat to the East of Los Angeles.

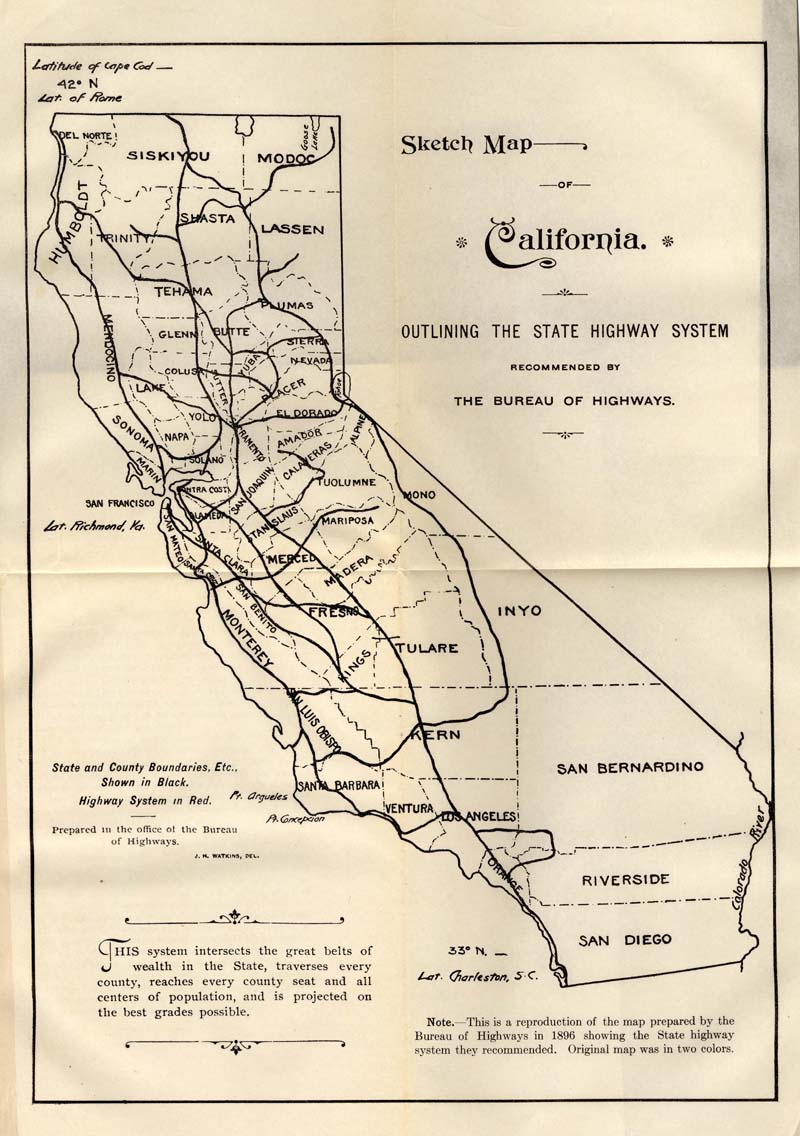

And those “Ranchos” were surrounded by even more “Ranchos”, bordered by the Angeles National Forest, Ventura County, and Orange County (which came by its name honestly), and the Pacific Ocean. The “Orange Belt Line” of the Southern Pacific was used as a means of travel to connecting Southern California cities; Riverside, Redlands, Pomona, Port of Los Angeles, Santa Monica, and Santa Barbara.

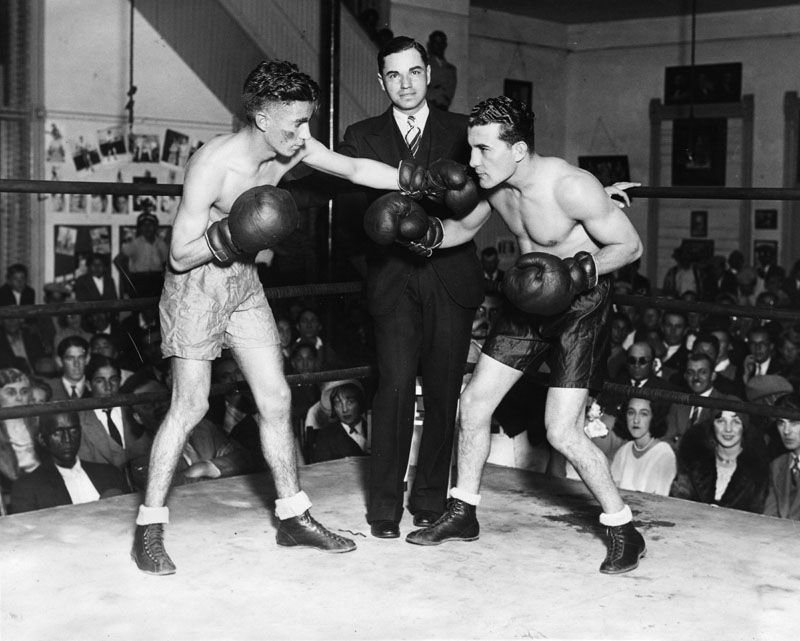

Entertainment at that time was sparse and varied because beyond farming and land acquisition there was very little to do in Los Angeles, — other than watching horse racing, boxing, or going to cribs, bars, and attending baseball games for amusement. Unless of course one was more prone to watching the errant gun fight, which could also be found near “Calle de los Negros“, or “Street of the Blacks“. Calle de Los Negros was an interesting plot of land at the core of early Los Angeles, which would also become Downtown Los Angeles, home to early film making in El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles de la Porciúncula. It was the place where Los Angeles began in 1781, and 42 of the original 44 Pobladores were “People of Color”. Over fifty percent of these early settlers were African Diaspora men, women, and children, — whose racial designation was based solely on the Spanish Casta system of lineage put in place at that time is was settled. Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd often used Calle de los Negros for location shoots, and other surrounding businesses as well — for many of their film classics. In early Los Angeles, it was all about the challenge. The hardened challenge. Building a city on top of the desert presented an immense challenge. Finding access to water presented a tremendous challenge. Even making a movie in those early days of Los Angeles presented a challenge. But coming from those challenges, or taking up those challenges, a great many things came out of those challenges, – whether they were win, – lose, – or draw.

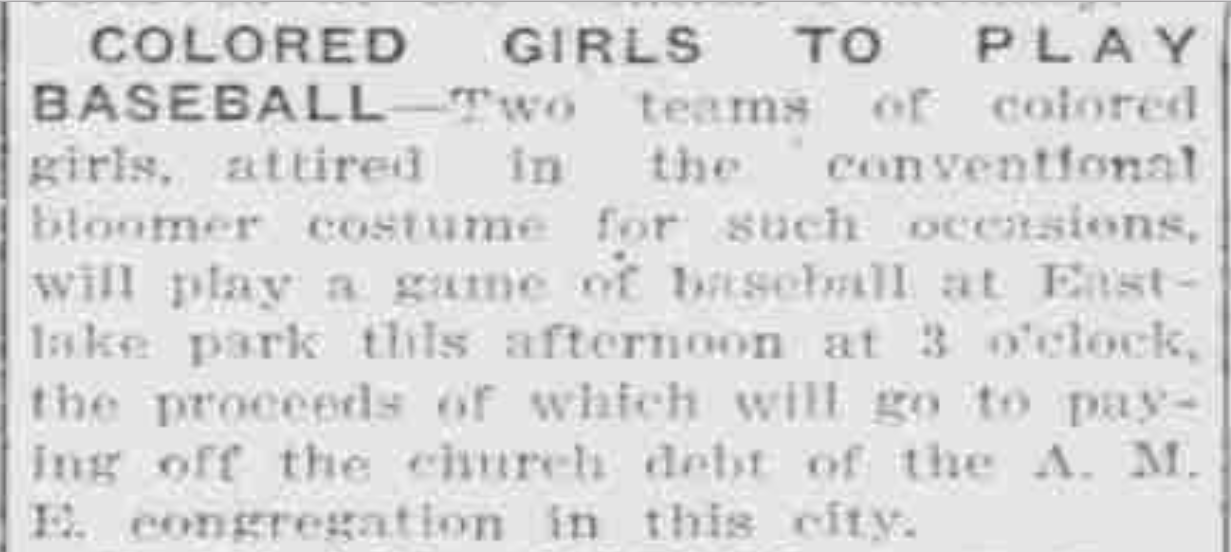

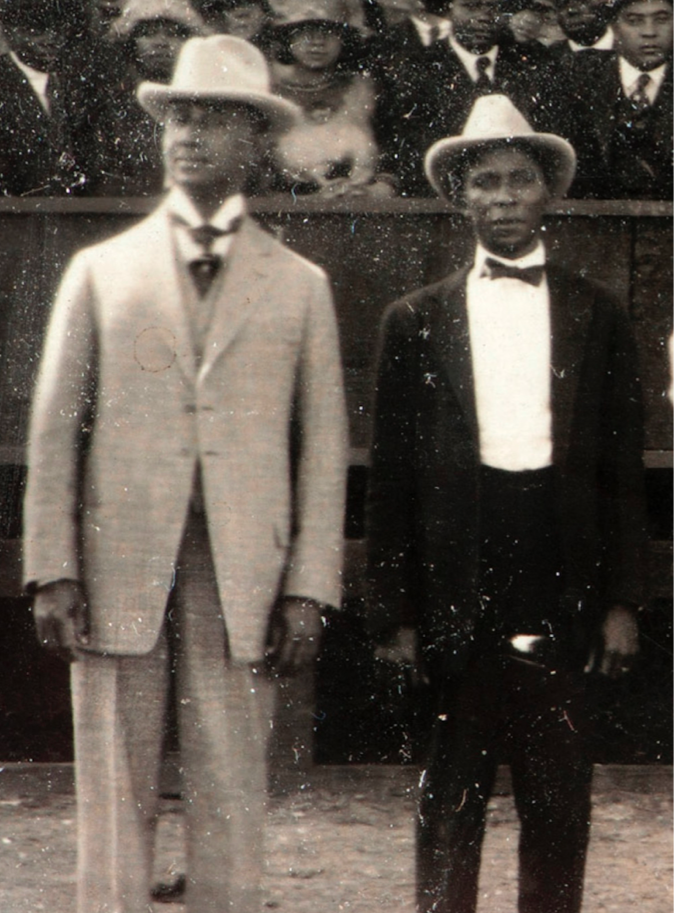

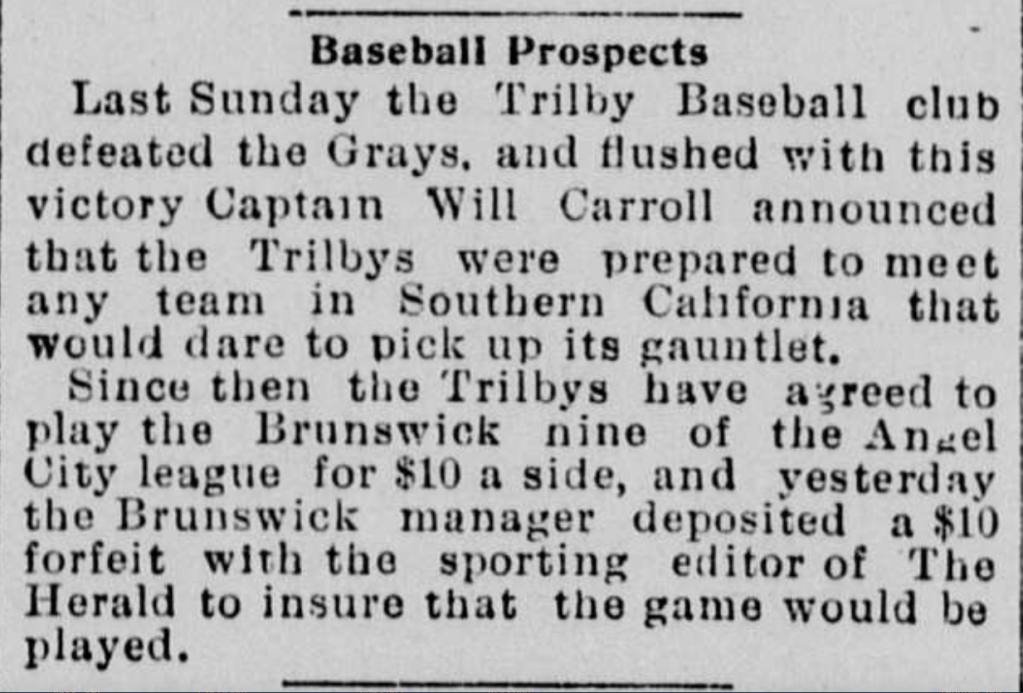

When William”Will” Carroll and James M. Alexander were presented with the challenge to field and fund an African American baseball club in early Los Angeles, which at the time was one of America’s most racist cities for that particular period in history, they both knew that the obstacles they would face would be almost insurmountable. No guts, no glory, as the story goes and with a boldness of heart, they placed their first advertisement in the Los Angeles Herald in 1895. It was a come one come all proposal, to watch the spectacle of this grand social experiment that was about to unfold before your very eyes. Baseball was seen as a white man’s game in Los Angeles, just like the rest of the nation, and when one was living in a white man’s world, black people and white people didn’t fraternize with each other, particularly on a social level. Especially in 1895 Los Angeles. 126 years ago, there was no question that placing such an advertisement in the newspaper could get them killed or lynched in Angel City. It was a brazen act of courage and very bold move on their part.

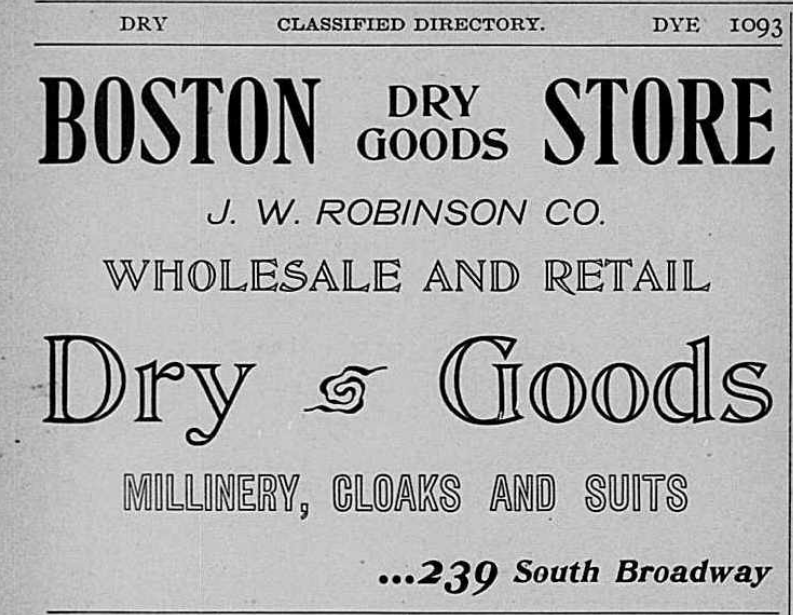

As a brakeman for the Southern Pacific Railroad Co. in the late 1800’s, “Will” Carroll was familiar with all types of danger. He lived his life fearlessly, atop boxcars, bringing them to a screeching halt if need be. He had connections, traveling from town to town. He had money burning a hole in his pocket that he had saved from his brakeman’s job, which would help him fund future endeavors. William H. Carroll also had dreams, and he would make those dreams come to fruition. James M. Alexander worked for J.W. Robinson Co. (Boston Dry Goods Store) as a ‘porter”, which this store in its modern incarnation would be known as Robinson’s Department Store, located at 239 South Broadway, in Los Angeles.

This store was a brand new facility in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles in 1895, and J.W. Robinson himself had moved his dry goods business to Los Angeles. Not just in the interest of selling dry goods, but for the twofold reason of developing orange groves on his property in Riverside, California. The West had gained the national monopoly on all oranges headed to the East Coast at that time, and the profit margins on Valencia oranges that sold to the East was huge. All of these occupations in early Los Angeles were desperately needed, and Los Angeles was soon to become a Boom Town. “Angel City” was the place to be, if your intent was to grow the unusual and the interesting.

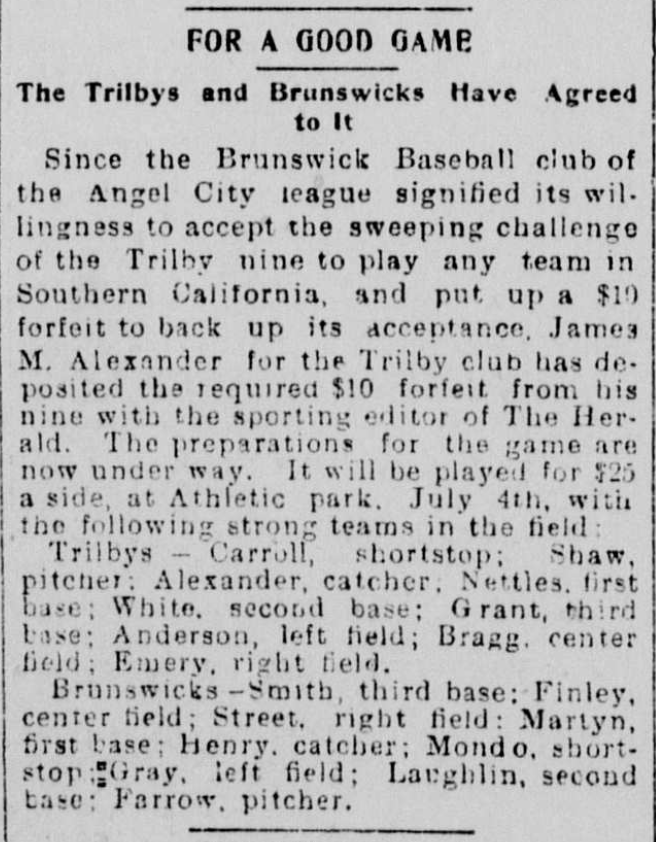

After the Trilbys defeated the Seventh Street Grays, Carroll quickly issued another challenge, and this time it is finally taken up by the Brunswicks of the Angel City league.

The chronicles of the “Trilbys of Los Angeles” is just a part of the story of Carroll and Alexander, and their early years in baseball. Before now, William H. Carroll and James M. Alexander of the Alexander Giants, and the Carroll Giants, A.C. Garden Athletics, Carroll Park and Alexander Giant Park have been sort of a mystery. Not unsolved; just untold for the most part. Their particular story travels backwards in time to their humble beginnings, sometimes bridging gaps and making connections for the purpose of telling the prequel narrative of how teams like the Alexander Giants came into being. Traveling through the netherworld of numerous sports articles buried in the Pre-Modern Baseball Era, which is the period between 1876 and 1900, can sometimes net positive end results. The story of the Trilbys of Los Angeles, and Carroll and Alexander is one of those tales.

From these three articles, one can glean the importance of the history of African American baseball in the West, that are as follows: 1) William H. Carroll and James M. Alexander located in the same place, at the same time, doing the same thing. Starting an African American baseball club in the early beginnings of Los Angeles, during the Pre-Modern Baseball era. 2) They also show baseball historians these two men inserted themselves in league play within an already existing all-white league, based totally on their financial means and baseball acuity. 3) It completes a three decade time line of William H. Carroll and James M. Alexander, and shows us as well, that not only did Carroll and Alexander front the Trilby team financially, but that they also played the sport of baseball as well.

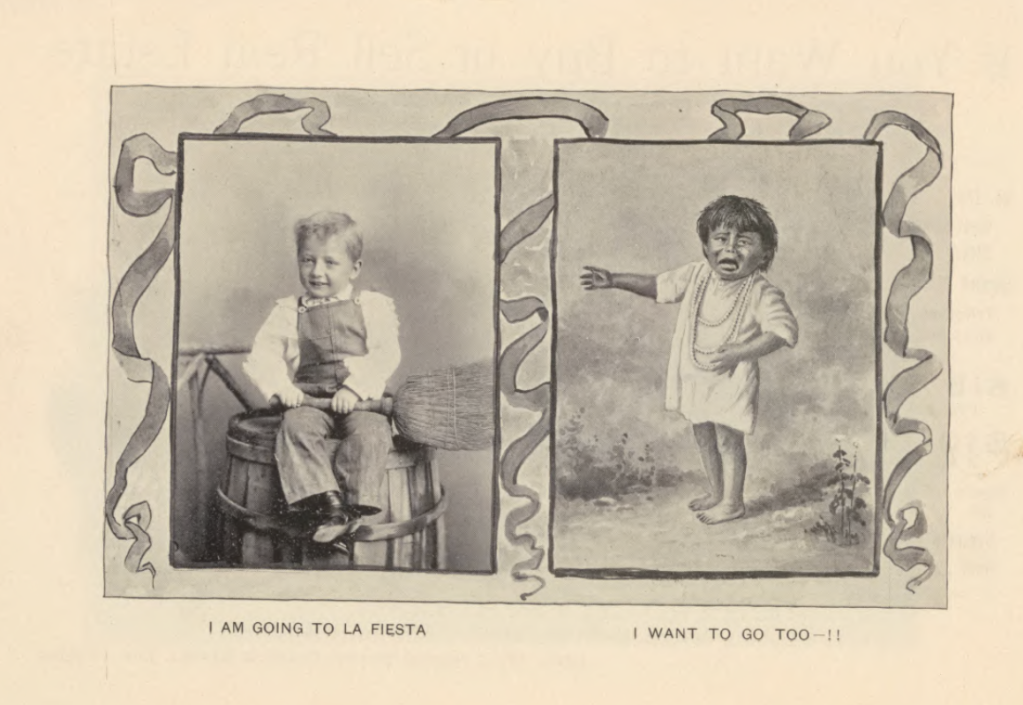

1895 was the year Los Angeles had its real coming out party, by way of “La Fiesta de Los Angeles“, which took place between April 15 and April 20 of that year. It was a strange event orchestrated by the Merchants of the Greater Los Angeles region, and one that was used to set the tone for the Greater Los Angeles area well into the final decade of the 19th century. On the surface, it was a seemingly harmless function given by merchants and political figures, but deeper down it was a culturally appropriative milieu of bad taste entertainment, which was used as a selling point for Eastern migration to Los Angeles. The festival which was similar in its design to a Mardi Gras pageant was largely filled with nativist propaganda, in search of those seeking out the final vestiges of Manifest Destiny on the Western frontier. It was an invitation from those in power to beg, borrow, and steal land, commandeer resources, and displace the indigenous peoples and remaining Californios, made up of mostly those who had already retreated from the majority of upper California after the Bear Revolt and Gold Rush of ’49, — and had already moved much further South than Santa Barbara County, to eek out what was left of a meager existence in the desert of Southern California. It was part of the Great Land Rush of 1895. The golden value in Los Angeles’ vast territory was found in available acreage, and much of it could be secured for a nominal price. When the first advertisement in the La Fiesta de Los Angeles program is for all the existing train routes and their access points showing everyone how to get there, and the second one is about real estate, then the Manifest Destiny of Los Angeles writing was on the wall.

“Just as the scope of La Fiesta outgrew the original design, so did the plans for the carnival of the present season assume greater magnitude. As a subject for the allegorical features of the street pageants it was decided to make the central spectacle descriptive of a period of wonderful interest, which has never heretofore been utilized in celebrations of this kind, the achievements of the Spanish pioneers in the great Pacific west of North and South America, and the striking customs and life of the strange races which they conquered, to be contrasted with the march of American civilization……” – La Fiesta de Los Angeles program, “The Carnival of 1895”.

Racism ran deep in early Los Angeles. Culture wars were very prominent, based on the remaining available real estate that had yet to be conquered and consumed by an ever increasing migrating population coming from the Eastern U.S. to the frontier Southwest by rail.

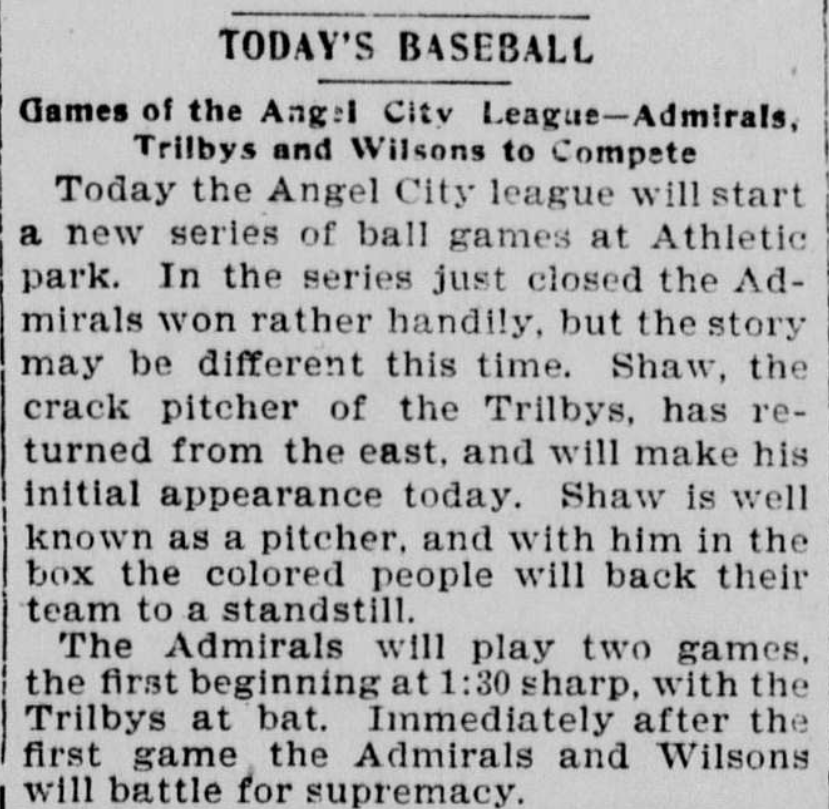

The staged “July 4th baseball” event took place. Two games were played on the Fourth of July at Athletic Park, to a crowd of 4,000 paying customers, who had certain expectations. Except the Trilbys did not play the Brunswicks. The Brunswicks played and defeated the Pomona ball club at a score of 9 to 6, and the Trilbys played and defeated the Boyle Heights Stars 19 to 15. The advertised game between the Trilbys and the Brunswicks was a loss leader pitched at Angel City league fans, and a very effective way to introduce the “Trilbys of Los Angeles” to the predominately white fans following Los Angeles baseball, who were unaccustomed to seeing an African American baseball teams in the Southern California area. The game between the Boyle Heights Stars and the Trilbys was more about brand building than anything else. To build anticipation of a crowd in search of new and exciting entertainment. In approaching the introduction of the Trilbys in this manner, the stakes were immediately raised to $50 per side for the Trilbys vs. Brunswicks, instead of the formerly agreed upon $50 winner-take-all pot, and the game between the Trilby and the Brunswicks was then rescheduled for July 15th, 1895.

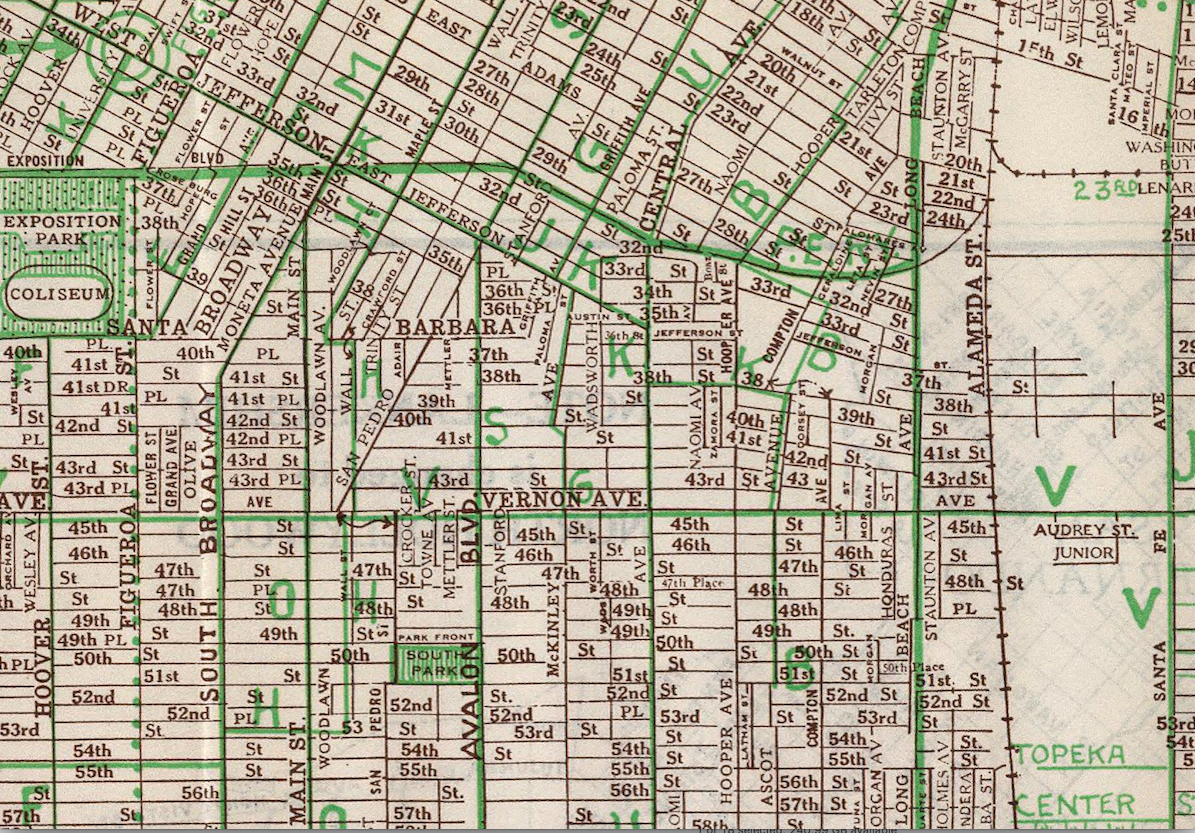

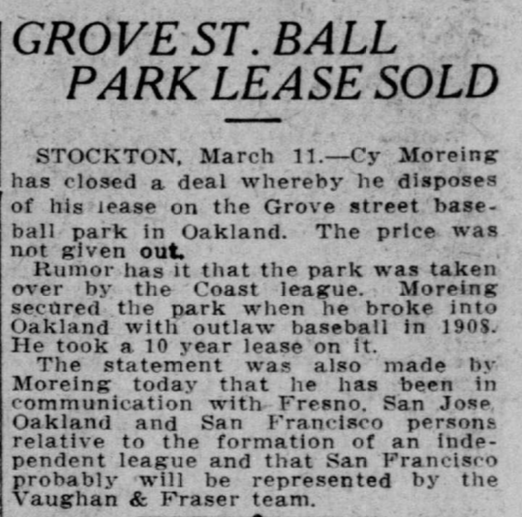

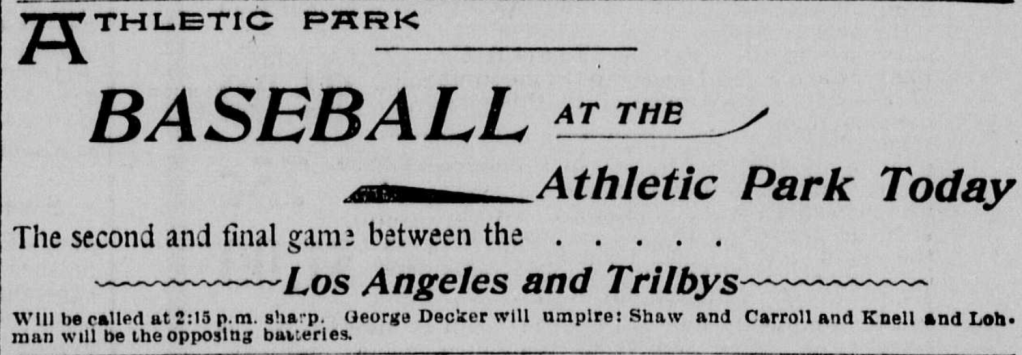

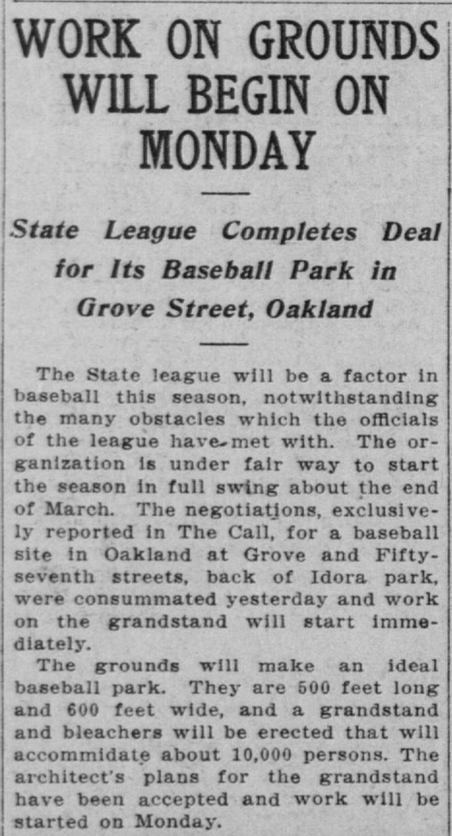

Overall, the 1895 season for the Trilbys, which was built purely on a challenges of team-against-team for winner-take-all, had thrust them quickly into the lime light of the Los Angeles Herald sporting section between 1895 and 1896. Los Angeles was still pretty much a horse and buggy town in 1895, unless one just chose to ride a horse without using a buggy. The first automobile appeared in Los Angeles in 1897, and ever since then Los Angeles has never looked back to its Golden Age of Buggies. Transportation to and from games limited the game play between the most teams, and mobility of the Trilby team was heavily impacted by this fact for the first couple of years, unless of course they played a team where a train station was located nearby. Athletic Park was their home field, for the most part, and they had to accept whatever games that came their way. As the story goes with the crash of the “California League” (The Los Angeles Angeles, the Oakland Colonels, the San Francisco Friscos, and the Sacramento River Pirates) in 1893, — Athletic Park was now used by the Angel City league for local ball games. Once home to the Los Angeles Angels, the very first professional baseball team in Los Angeles, which played between 1889 and 1893, Athletic Park now fielded local teams. Distance between California League locations was a dominate factor which help kill the early California League.

Yet in February of 1895, the town of Los Angeles came together and decided to play baseball again, after a consecutive two year lull. They had a park, so why not? The creation of the Angel City League would be a boon to local businesses, and give people something that involved the entire community. In the beginning (1894), there were only four teams that fit the bill for scheduled play at Athletic Park. The Francis Wilsons, El Telegraphos, the Keatings, and the Boyle Heights Stars.

By 1895, the El Telegraphos and Keatings teams would be replaced by the Brunswicks and the Admirals. The Keating were named after the Keating bicycle, carried at the Hawley, King & Co., purveyors of fine carriages. Mr. A.B. Boswell was manager of the Keatings, and had been recruiting the best amateur baseball players in Los Angeles since 1892 when he managed the Long Beach baseball club. Which bring up another interesting point about early Los Angeles. The bicycle was a common mode of transportation within city limits, and there were a multitude of bicycle shops on Spring Street in early downtown Los Angeles.

Fowler Bicycle Co. was located at 431 So. Spring Street, in Los Angeles. It was such a popular bicycle shop, it boasted five employees. Will Knippenberg’s bicycle works, located at 437 So. Spring Street, sold the Crimson Rim “Syracuse” bicycle in men and women’s models, and tandems bicycles as well. The average cost was between $105 to $155 for a bicycle, and this mode of transportation for growing city was no longer consider a “fad” to the uninitiated. W.K Cowan sold “Rambler” bicycles at his 427 So. Spring Street location, and had 18 models to stock to choose from. The bicycle was a integral part of the growth of early Los Angeles. It was also beyond the meager means of of the average person.

The Keating Bicycle and the Keating baseball club were good ‘product placement’, just like the ‘Trilbys of Los Angeles’ were good product placement.

Carroll and Alexander both possessed entrepreneurial spirits from the time that they met. Both were fairly self-educated men. They both could read and write even though they had no formal schooling, and both men had a excellent sense for business. They knew how to parlay a few dollars into a larger earned equity. They were an exception to the rule for men of that period, who were black or white, and especially for fast growing place like Los Angeles.

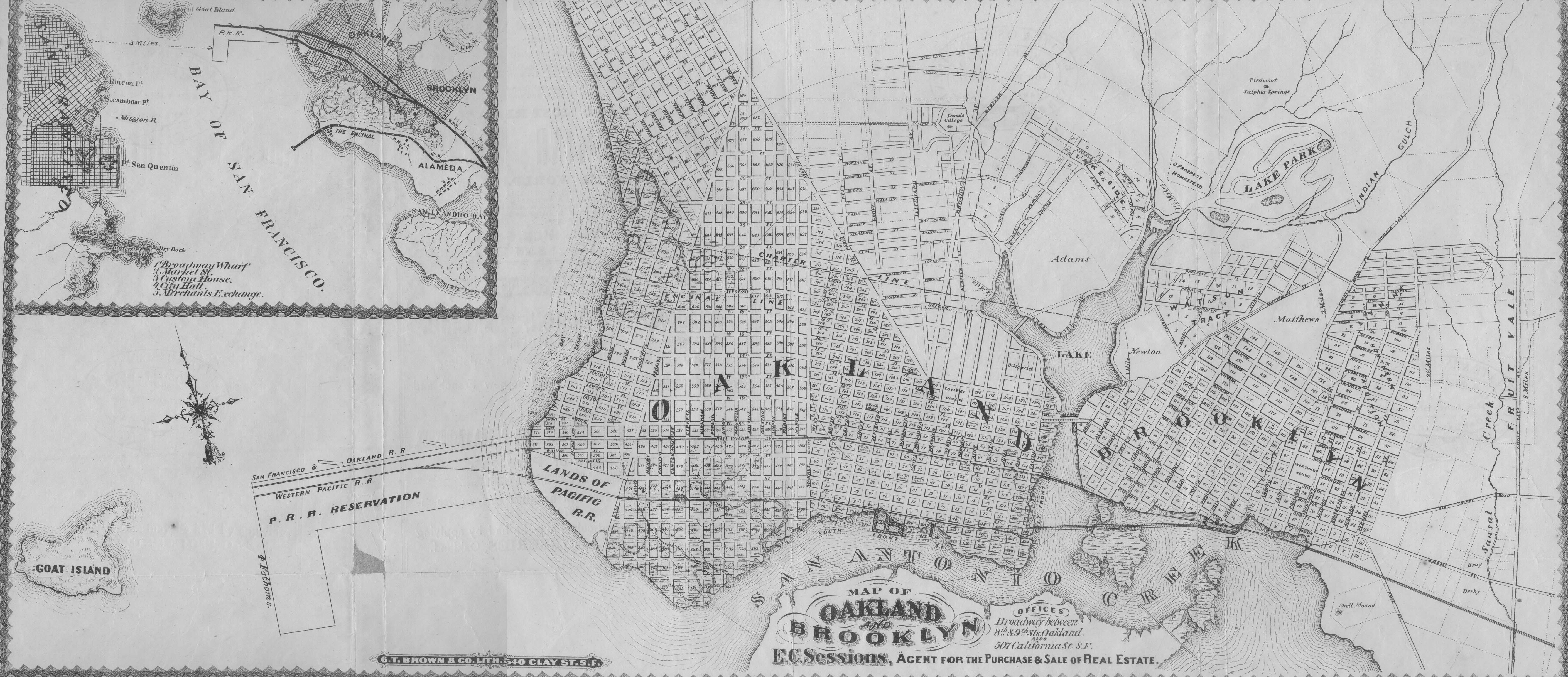

Carroll was born in Virginia in 1865 and Alexander was born in Texas in 1872. What they both had in common was that both of these men never ever wanted to return to their place of origin. The West was seen as the land of ‘milk and honey’. The West was the the land of vast opportunities. The West was pliable, — where a man could mold his future. And, in “Boom Town” Los Angeles, Carroll and Alexander were only a train ride away from Oakland if things got too dicey. Also, Los Angeles was a town just dying for baseball. And the Trilbys were the only ‘black baseball team’ for hundreds of miles around, which gave Carroll and Alexander just the advertising edge that they needed to make a name for themselves and their Trilbys of Los Angeles.

In 1894, the Angel City league had scheduled 24 games between the four existing teams. Two games, each Sunday, would take place at Athletic Park. By the time 1895 rolled around, the Angel City league had reduced the schedule to 20 games between the four existing teams, giving Carroll and Alexander the perfect timing to set up challenge games. With two games with alternating teams, taking place at Athletic Park each weekend, it was their chance to be seen on a regular basis. The introduction of the Trilbys into adolescent Los Angeles society was just the equation of additional weekly baseball needed for the local betting pools and colorful entertainment of the ever needy Los Angeles.

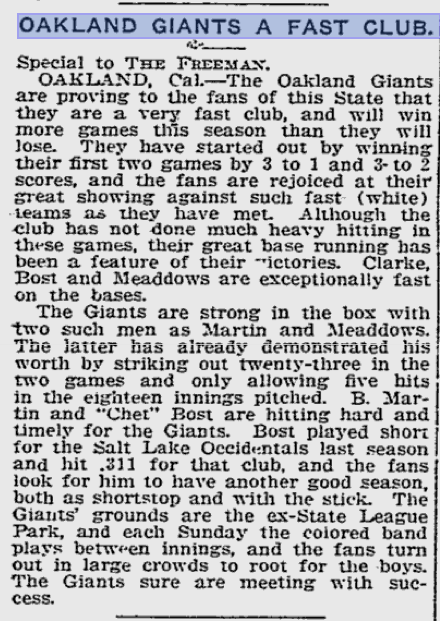

Los Angeles was a gambler’s paradise. With alternating teams playing each Sunday, and games taking place at Athletic Park, the city of Los Angeles was proving that it could hold its own in the world according to the national pastime. Introducing the Trilbys into the burgeoning city of Los Angeles, and restructuring the racial exposure equation into weekly baseball games, added zest and vibrancy to the local betting pools and colorful entertainment of the ever needy Los Angeles population. Between June 17, 1895 and Oct 28, 1895, the Trilbys played twelve scheduled games and winning a total of six of them. They boasted one tie to that record. Most of their games, with one exception, were played against teams that existed within the Angel City League. It was the preemptive beginning to the desegregation of the Angel City league by way of challenge, which also proved to be a tremendous boon to local businesses. Los Angeles would become the Trilbys’ “Eldoradoville“.

And although they were “not officially” in the Angel City league, the Trilbys would make a showing in the year of 1896 as well. The Trilby of 1895 racked up a lot of wins, and as many losses, but their persistence and method of advertising brought them the notoriety that they’d been seeking since their initial challenge to one-and-all in the Southern California area. Athletic Park, located in on Alameda Street, bordered by the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks just South of the Southern Pacific Arcade Depot, between Palmetto and Seventh, was a place where the Trilbys played a majority of their games, and was quite well known throughout the region. Athletic Park was built on land that was once owned by William Wolfskill, pioneer, viticulturist, and agronomist, who developed the Valencia orange. The Wolfskill Ave. Winery was still in operation during this time, and was located on Ceres Street, not far from the Arcade Depot.

More importantly, the Trilbys themselves became a regional draw and the local fans enjoyed watching this African American team win or lose. A lot of hype was built around them, and their showmanship and fine ball playing skills were their team’s branding trademark. This is what Carroll and Alexander were hoping to establish in the city of Los Angeles. The Trilbys were the wildcard team, unpredictable, and a thorn in the side of the Angel City league teams; which kept the bookmakers, and local as well as distant odds makers, wondering which team within the all-white Angel City league were truly league champions.

The Trilbys had rightly earned their nickname as the “Colored Terrors”.

After the Trilbys opening season loss to the Mount Lowe Boys at Athletic Park, by a score of 27 to 24, they once again found themselves being challenged by the Francis Wilsons for $25 a side, — for a $50 total “winner-take-all” contest, including the entire gate. The Wilsons, of course, were looking to redeem themselves to the local fans, after losing this same exact bet to the Trilbys in September of 1895. It was a sucker bet. On June 14, 1896, the Trilbys once again, took the win, took the money, and took the gate as well — by a score of 11 to 9. This continuous established pattern of losing to teams outside of the league, in order for the Trilbys to win games against teams within the league, was becoming clear to those with discerning eyes. Carroll and Alexander knew how to turn a buck, elevating the “double-or-nothing” stakes when bets were on the line, and promote the Trilbys at the same time.

It was on July 12, 1896, that the Triblys were mentioned in the Los Angeles Herald as one of the teams belonging in the Angel City league. This was a first in the Angel City league history, and it was hard earned. The Trilbys continually brought the Los Angeles baseball crowds to Athletic Park.

The “battle for supremacy” was played both on the field and off the field. The Trilbys always played good to great games, but always got second billing in the Los Angeles Herald, even when they won games. When they lost, they lost big. The team and its players were rarely mentioned in the sporting news. There was only box scores and no blow by blow of their baseball skill sets in their first two years on the field. The losers of the Angel City league teams got more press than the Trilbys did, until July 20, 1896, when the Trilbys played the Francis Wilsons in a fourteen inning tie breaker, where the Trilbys came home the victors, by a score of 7 to 6. Five extra innings of hard play after nine long innings, was referred to as the “prettiest game” ever played at Athletic Park. This would be the first time Los Angeles Herald would introduce the citizens of Los Angeles and Southern California to the Trilbys as something special, other than the normal mention as the “colored team”.

The Trilbys became the team to beat in 1896, and they played well into the winter, and advertisements were beginning to be used to promote their games. They played more than twenty-five games in 1896, and most of them were against teams within Angel City league. They even considered themselves the ‘league champions’, based on the amount games they played and the amount of games they won against their rivals.

From a once meager 24 scheduled games in 1894, with the addition of the Trilbys to the Angel City league in 1895, to the games played by the Trilbys in the Angel City league in 1896, — the Angel City league would now see an extended schedule of 54 games ‘games to be played’ heading into the 1897 season, with the Francis Wilsons playing the first game against Los Angeles ball club, and the Trilbys playing a second game against the the Francis Wilsons as the season opener. As the 1896 season ended, and the 1897 season began, the harsh reality of Southern California racism began to creep slowly into the concept of having an African American team defeat all-white teams without pause, within an all-white league.

The Trilbys had succeeded where they were expected to fail. The Los Angeles Herald, nor the Angel City league would never outwardly acknowledge their overall statistic within the Angel City league play, or recognize the Trilbys of Los Angeles as league champions. Whatever social aspects of racism that had been embedded in Southern California since before the Civil War had remained unimpeded by the South’s loss. Southern California had remained a Confederate stronghold, even though California was always a “Union state”. It operated socially and similarly under the same principles as the Gadsden Purchase of Arizona and New Mexico, absent of a land purchase and a line drawn in the sand.

The fight for baseball supremacy in Southern California was far from over.

Being referred to as “the colored champions of the state” by the Los Angeles Herald, and not the “Angel City League Champions” was basically a slap in the face to Will Carroll, James M. Alexander, and the entire Trilby organization. The bar was being set higher for being league “champions”, and the finish line was being moved further away. The new season began slowly for the Trilbys. Between May and June, the Trilbys racked up a series of losses, and didn’t come back to life till July of 1897. Most of their early games were played against teams that lay outside of the Angel City league. San Bernardino, Redondo, Compton to name just a few. The Angel City League was reaching outside of its normal area of operation, and inviting more all-white teams located in Orange County and San Bernardino County.

From the standpoint of Derrick Bell Jr.’s assessment, one of the main key components of Critical Race Theory is when a “dominant society racializes different minority groups at different times, in response to shifting needs such as the labor market.” This is what happened with the Trilbys while playing within the Angel City league and how the Los Angeles Herald portrayed them in ‘minstrel like’ illustrations along with the box scores of their losses. This had never been done until the 1897 season rolled around. But money and prestige were on the line now, and the Trilbys were being cut out of both.

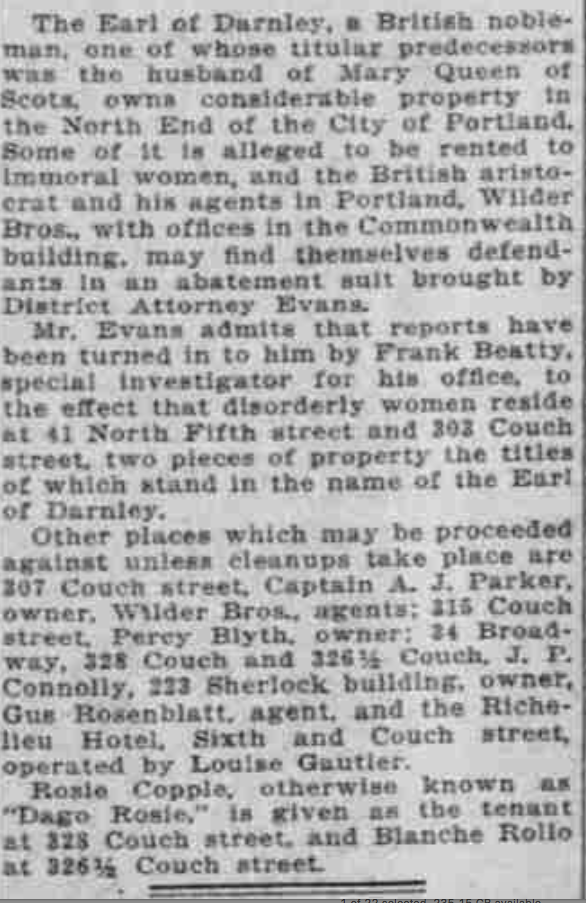

By 1897, Los Angeles was trying to clean up its act, which included demolishing all of the brothels and cribs that ran the length of Alameda Street and operated openly for decades. They were reminiscent of “Maiden Lane” in San Francisco in the 1860 to 1880’s. They were to be shut down at all cost. Those horrid dens of iniquity that resided between the warehouses, North of Aliso Street and Calle de los Negros. George Lecour, Joseph Wiatt, Blanche Laborde, Louis Exgris, Emile Rottenbeck, and Oscar Wagner who all rented cribs from the notorious Shafer Bros., were all put on notice, based on land leases that expired within Los Angeles city limits in 1897.

Bartello Ballerino, a wealthy property owner in early Los Angeles was by far the largest operator of brothels and cribs in this location, and in 1897, was said to have been worth the royal sum of $250,000. His wealth accumulation came to light when his wife filed for divorce, and his actual assets were in question. “Sporting Guide: Los Angeles, 1897“, written by Liz Goldwyn, granddaughter of producer Samuel Goldwyn, weaves an intricate tale of the seedier side of 1897 Los Angeles. Also, there were five hundred plus oil wells operating within Los Angeles, which made California the third-largest oil-producing state in America; so Los Angeles a a city was overdue for an extreme make over. What followed along with the clean up of Los Angeles though, was the elimination of the Trilbys from Athletic Park and the Angel City league, and the African American fans that followed them there in support of their games.

On July 4th, 1897, the Los Angeles Herald reported that the Trilbys had picked up two “new” players from the Pomona team. One can assume that these two new players were of African American descent, based on the existing racial dynamics taking place in Los Angeles and the surrounding areas. Pomona (in “Rancho San Jose”) was located near the San Bernardino County line, and at a great distance from the city of Los Angeles. Even though there was limited integration within the Angel City league, there was no real integration within individual teams when it came to scheduled games. On October 25, 1897, a “Championship Series” was announced in the Los Angeles Herald for all the teams that were currently playing in the Angel City league. There were some late comers, and unknowns who had embedded themselves in the Angel City league, which created a rivalry between those who had been playing since the season began.

With the 1897 season drawing down to an end, and with nearly no games scheduled for the Trilbys between June and September because of the introduction of these league newcomers, the ever reliable Trilby’s were now being scheduled to play nine games between October 31, 1897 and January 2, 1898 within the Angel City league. They had been left out of most of the regular season scheduling purposefully, and picked up games outside of the Angel City league whenever and wherever they could, just to keep up their skill sets. By October 18, 1896, the Trilbys had already completed 22 games within the Angel City league. By October 25, 1897, the Trilbys had played less than 9 Angel City league scheduled games. A this point in the 1897 season, even if they were to win all remaining 9 scheduled games left to play, the Trilbys would be out of the running for a championship play-off series. They had only accumulated 3 wins within league play by Oct. 25, 1897, there was no way possible that they could redeem their current League Champion status.

This newly conceived schedule and Championship series didn’t really matter though. In its entirety, this scheduled series for the ‘Championship of the League’ fell apart shortly after the games played on December 20, 1897 had concluded, and the city’s patrons were heading into the Christmas holidays. Any remaining league games that were scheduled to be played at Athletic Park, were replaced mostly by teams from out of town who were not in the Angel City league. The Southern California Championship series of 1897 for a purse of $200 was a total bust. it really never got off the ground.

The 1897 Angel City league season ended poorly for the Trilbys, by racking up more losses than wins and playing far less games than they had in their previous seasons. It was almost as if the Trilbys were being scheduled to not play games within the Angel City league, and being formerly a gate staple and a large draw within the Angel City league, the city of Angel City league didn’t really allow them to set their own schedule of games, or commit to the outside of the league table bets. Out of announced 54 scheduled games for the Angel City league in 1897, the Trilbys were only scheduled to play in a total 16 total, and that was by pure fluke.

The Angel City league scheduling had become awkward, uneven, an ill managed. Most of the teams that played that year were unstable and unreliable. Side bets were off the table. And the expansion of the games played with teams from Orange County and San Bernardino County only caused confusion and indecision when it came to scheduling game dates. Any money earned from the games played was not a matter of public display or public discussion.

With this international conflict between the United States and Spain moving closer to full military engagement, and the annexation of Cuba on the horizon, the multi-million dollars in trade losses with Cuba were on everyone’s mind, including Los Angelenos; and the main reason the U.S. would finally decide that an eventual military intervention would become necessary to secure the well being of the homeland. Baseball leading up to the 1898 season took a back burner to this predetermined war with Spain. Heavy economic losses to the United States were mounting, and were on the minds of all Americans. The conflict with Spain would also have a tremendous effect on the status of the “Sandwich Islands”, and would spread to all of the Spanish East Indies colonies, including the “Pearl of the Orient“. Not only as replacement as trading partner, but also as a forward base of operation for the impending war with Spain in the Pacific as well.

When the U.S.S. Maine was sunk on February 15, 1898, the focus of the United States shifted from baseball to war. In fact, there was almost no baseball to speak of. What began early in the season died quickly, and painlessly, because there were no teams playing the game of baseball in Los Angeles, except for the Trilbys, the Spauldings, and the Los Angeles Stars for the most part. And even those games were infrequent occurrences at Fiesta Park or Athletic Park. At the end of the 1897 season in mid December, it has been rumored among the financiers of the Angel City league that there would be sponsorship of a “Southern California” league, with leadership stationed in San Bernardino, instead of Los Angeles, and this new league would use teams who would come from as far away as San Diego. There was never any mention of such a league developing in the year 1898. In Los Angeles, there was very little baseball talk at all.

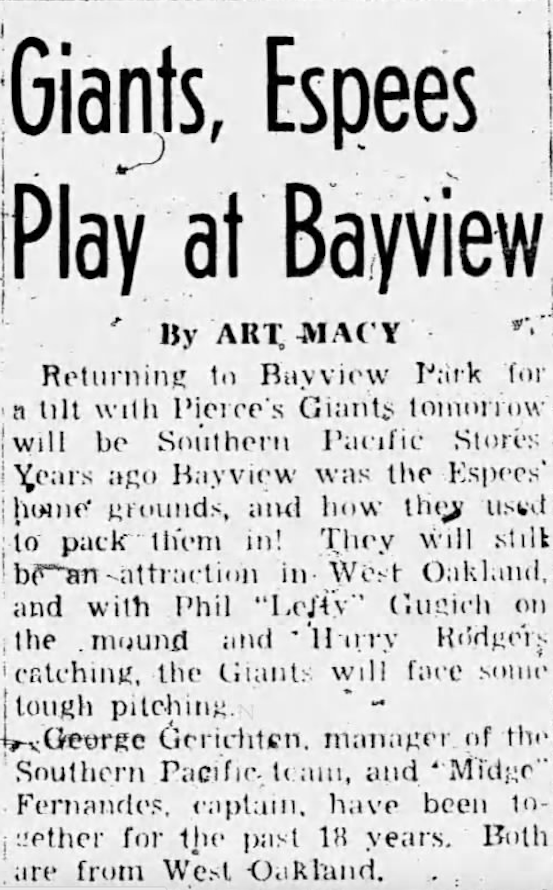

After a two year lull in playing, or trying to make sense of why the Trilbys could not get any steady action on the field, Will Carroll decide that is was time to take it back to the very beginning. The Trilbys had suffered an embarrassing defeat against the San Diego team in April of 1899. The main reason that was given is that the majority of the Trilbys’ regular players could not afford to travel to San Diego, so Carroll put together a makeshift squad of players who could go travel to Bayview Park. They were also playing in unfamiliar, hostile territory. What Carroll had learned from that defeat was to bring the game, his game, — back home. And the only way to do that was through advertising his desire to engage in the sport with all comers, invite one-and-all to play against the true Champions of Southern California. Just like he had in the past, Carroll set the tone.

The Call Out; the “challenge” to his opponents was a trademark of Carroll’s magic on and off the field.

Carroll enlarged his target market by staking the claim that his Trilbys had been the “Champions of Southern California”, and not just in Los Angeles. Once again, his ruse would be just enough to gain him the public’s attention, and peak the ire of those who had been planning something much different for the Trilbys when it came to Southern California baseball. Losing was part of playing, and Carroll knew that. What was worse than losing though was not playing at all, or not being allowed to play at all. Carroll went on the attack and reorganized the Trilbys in March of 1899, with James M. Alexander still being a part of the team.

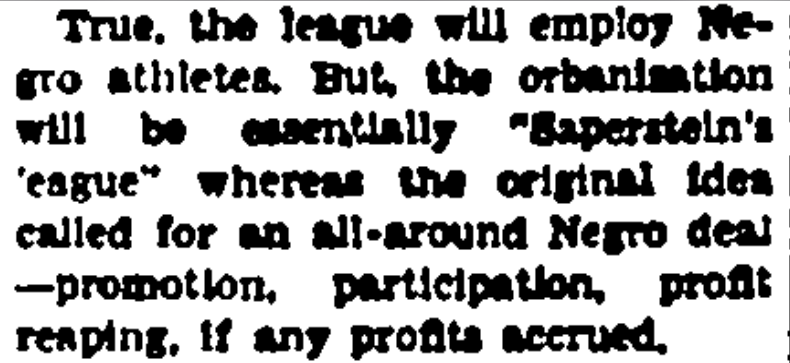

After the 1899 season opener, where the Trilbys lost the game by 28 to 4, and the newly formed “Southern California League” made the executive decision that the Trilbys were not “up to the mark” of playing that the league required. The Trilbys had lost games before, and had went on to defeat the teams that had previously defeated them. A single game where the Trilbys lost, it was announced that the Trilbys would not be a part of this new Southern California league, which was operating outside of Los Angeles county proper. It was something that Carroll had suspected all along.

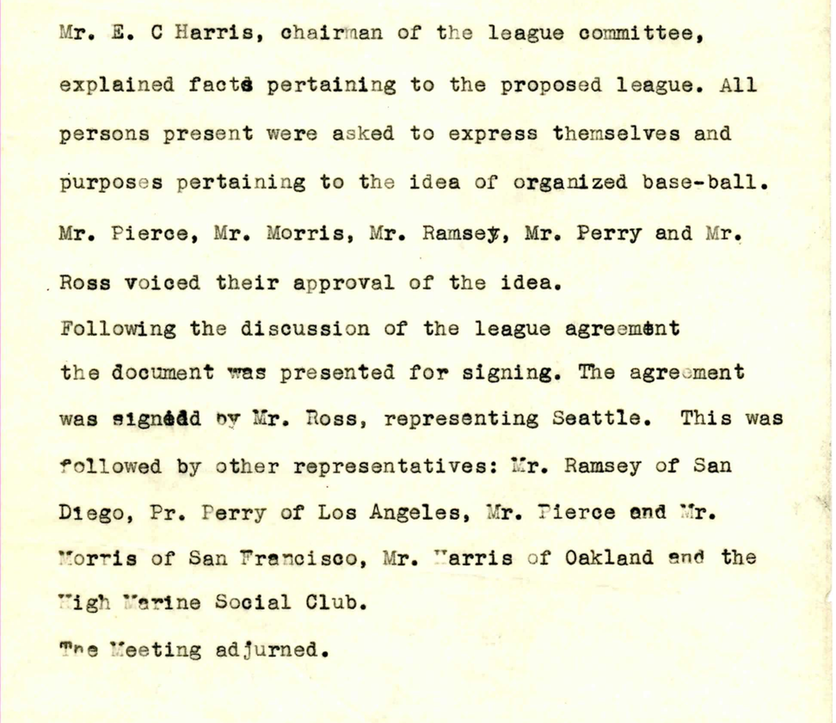

The fact that the Trilbys often sandbagged games, so they could raise the betting stakes didn’t help their introduction to this newly formed league, for this was not solely a Los Angeles league now. This was San Diego headed league, where bush ball was taken extremely seriously, even if they thought more highly of their organization than the former Los Angeles Angel City league had. The main funding for this new league came directly out of San Bernardino, and it was financed by W.E. Collins and George Cobb. J.M. Dodge, President of the league from San Diego team, along with George Cobb of Riverside, who is Secretary of the newly founded league.

In a stroke of genius, and tenacity, even though Carroll’s Trilbys weren’t getting as many games as they should have, and by being ostensibly shut out of the Southern California league, Carroll began his own self promotion by stating he was in contact with Bud Fowler‘s “Colored All-American Black Tourist“, and he and Fowler were in negotiations with him to catch for the team. It was the kind of publicity that could not be ignored by those who were empowered in the Southern California league.

The Trilbys wasted no time in seeking out games. The locales of these pick up games made no difference to the Trilbys after the reorganization had taken place. Carroll set up matches with old opponents that were not in the league, like the baseball club from Redondo. And they waited patiently till the two other teams from the former Angel City league, the “Merchants” and the Los Angeles Stars played against each other, to see who was in better form within this new Southern California league. And then they outwardly laid down a challenge to the winner of a series between the two. It was a pure bravado move on Carroll’s part. Not only did the Trilbys challenge the “Merchants” to a winner take all contest, they played the game at San Diego’s Bayview Park, for one-and-all to witness on the Southern California league’s turf. Will Carroll managed to to all this while securing games with other teams in Northern California.

The years between 1898 and 1900 were lean times for the Trilbys of Los Angeles, but Carroll was persistent if nothing else. The ever changing face of Los Angeles, was moving towards a more civilized environment and much further away from its harden “Old West” image. Los Angeles was in the beginning stages of creating an image that was “family friendly”. It began with the shutting down of brothels, cribs, and opium dens in 1898, and that purge continued well into 1900’s, with the closure of saloons and other drinking establishments, based on new sanitary laws and restrictions imposed by the City of Los Angeles. In the year 1900, the overall population Los Angeles had reached 102,479, and was consider the 36th largest city in America.

And even though Los Angeles had the 2nd largest African American population in California, those 2,131 African Americans still represented only 2% of the total population of Los Angeles. Will Carroll must have had foresight into the development of of early Los Angeles, for he’d taken his earning and invested in a saloon and hotel located at 102 North Los Angeles Street near Calle de Los Negros in 1898, called “Carroll & Brown“. By 1899, Carroll bought out his partner,– the ever elusive “Brown” –, and renamed the drinking establishment “Carroll’s Place“.

Carroll’s establishment was located two blocks South of Calle de Los Negros, and three blocks South of El Pueblo de Los Angeles and Los Angeles Plaza, where Los Angeles began.

Playing outside of the Southern California league and consistently winning proved to be beneficial for the Trilbys and Carroll. Carroll and Alexander, as businessmen and sportsmen, had made it this far by playing the long game. If the powers that be would not allow the Trilbys to play in the Southern California league, based on continued overt racism, then the Trilbys would defeat as many teams as possible outside of the league, thereby encircling the Southern California league with a multitude of games played and games won for side bets, and their entertainment value. This kept the people of Southern California in heated discussions about who played the best baseball in the Southland.

Between 1900 and 1905, the Trilbys under William Carroll reorganized the the team one last time in 1904. The year 1902 was the most revealing eye opener to Carroll though. What he knew to be true had finally come to a head. Being the outspoken man that he was, he wrote a letter to the sporting editor of the Los Angeles Herald about his ill treatment in Santa Ana. Carroll had finally had enough of the blatant, overt racism and game fixing that was being played out by the Southern California league or other teams under the guidance of those that lived outside of Los Angeles County.

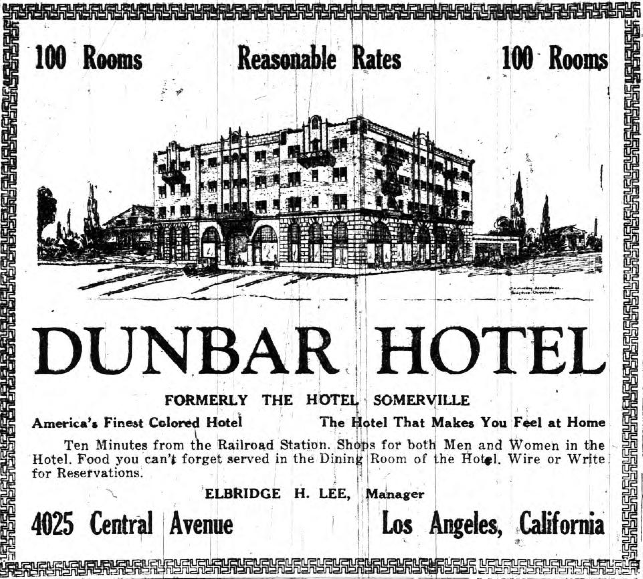

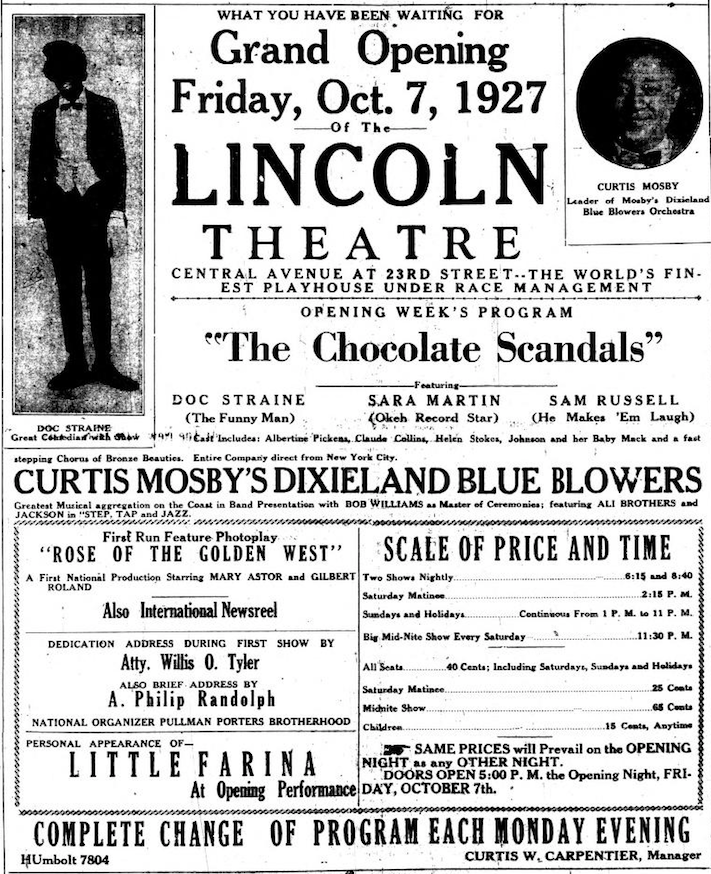

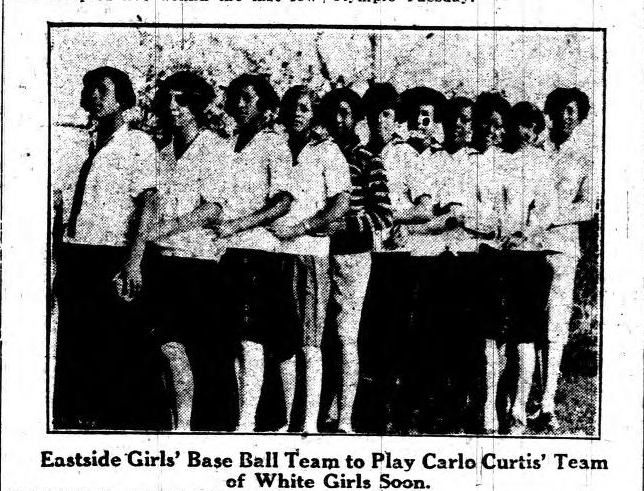

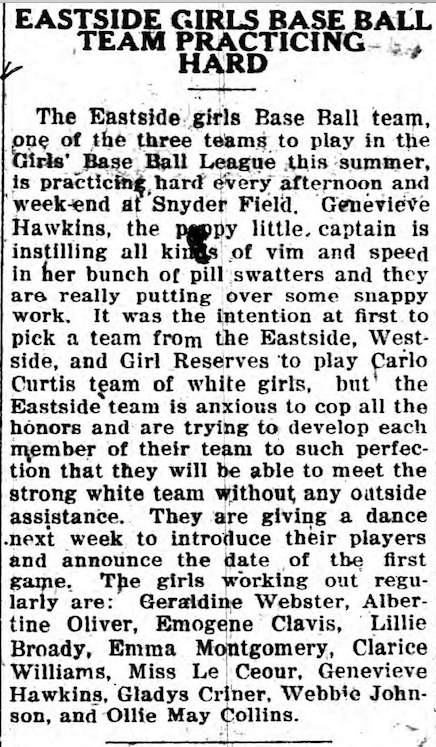

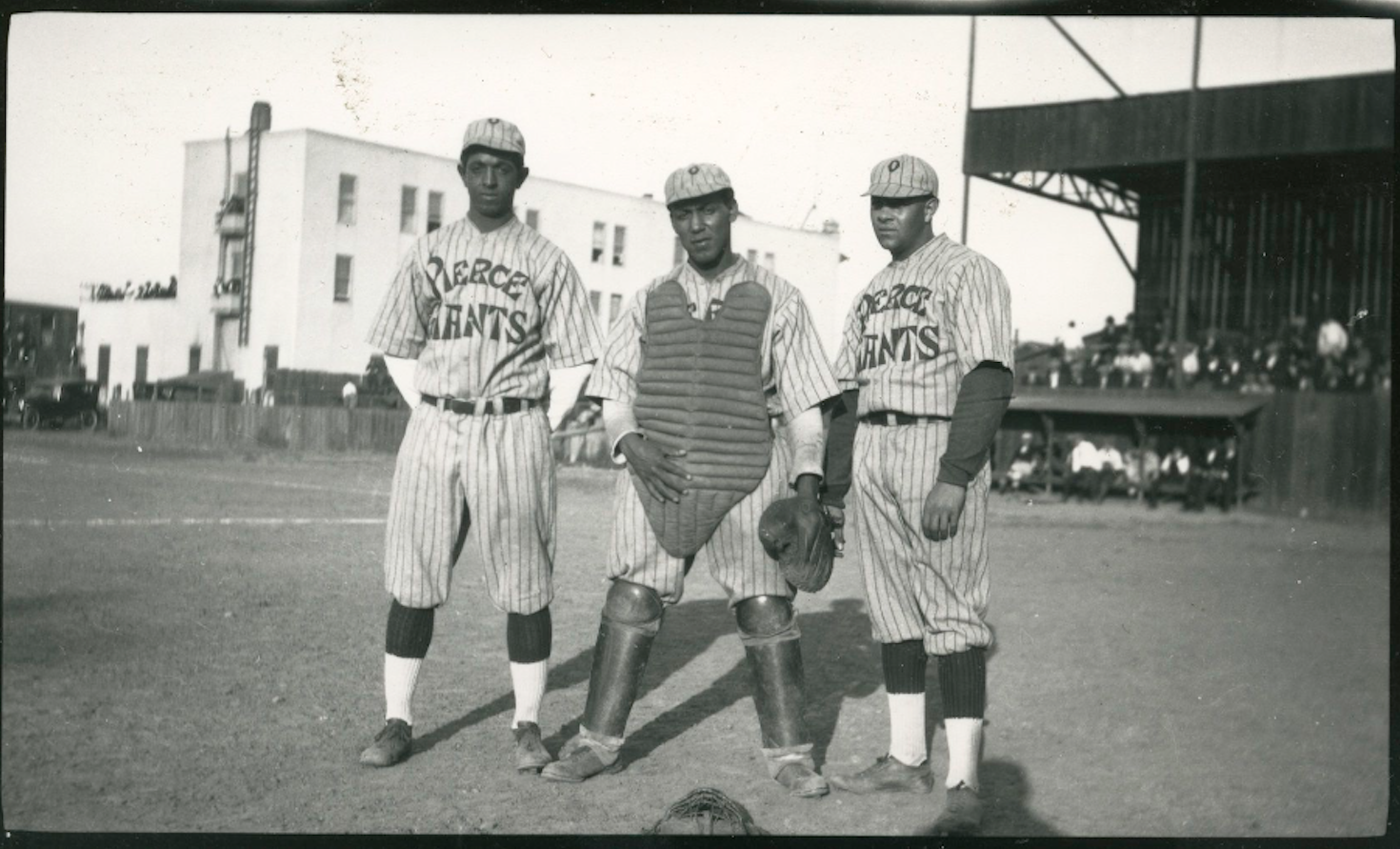

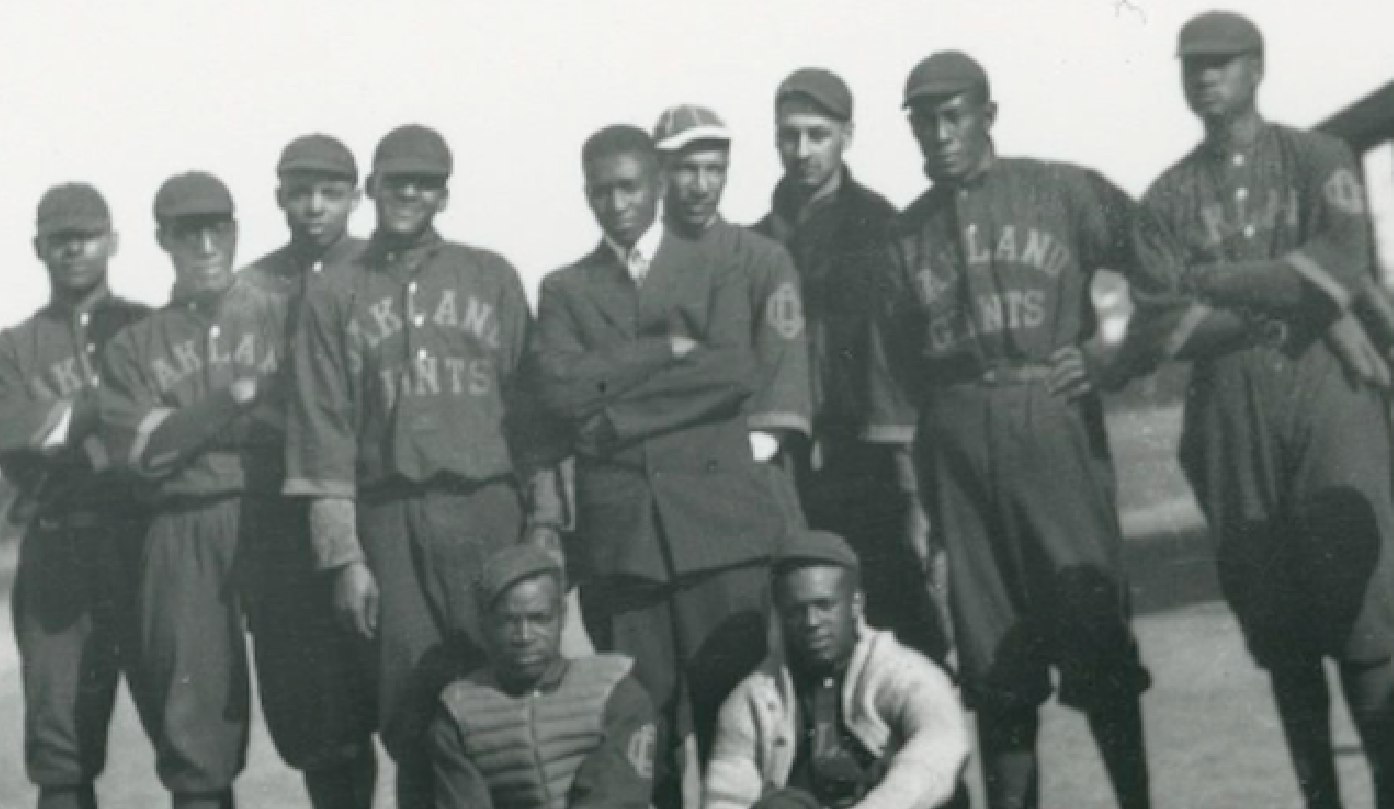

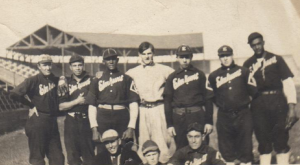

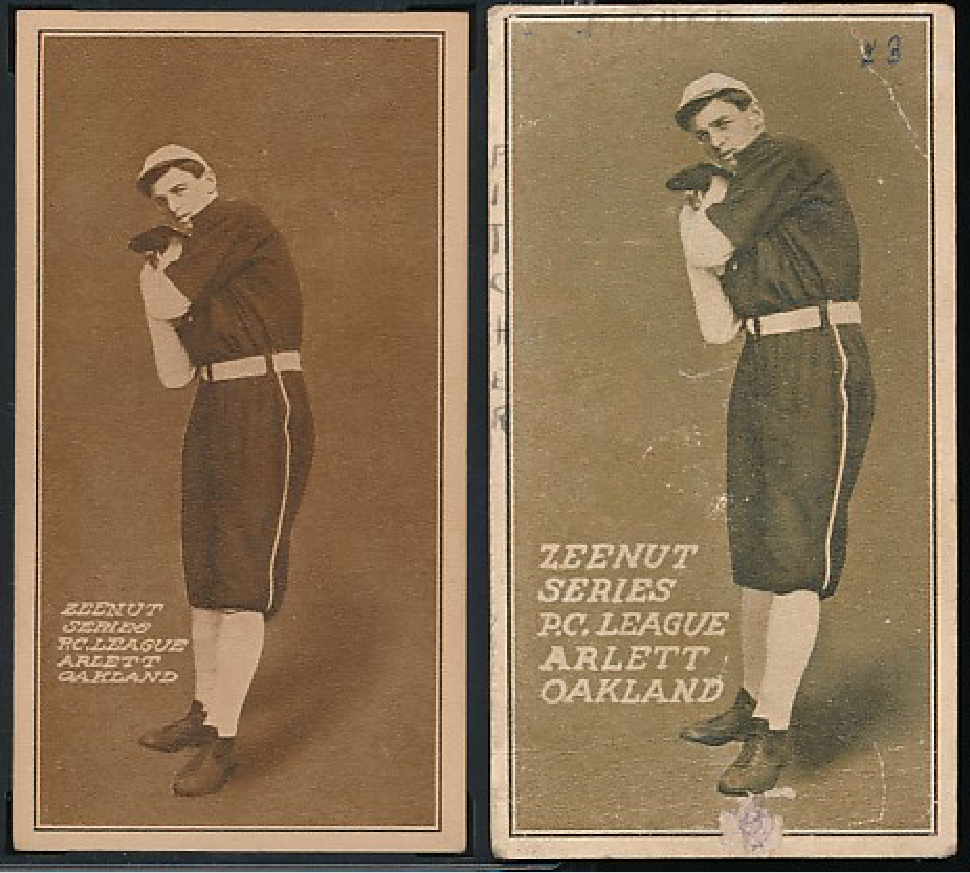

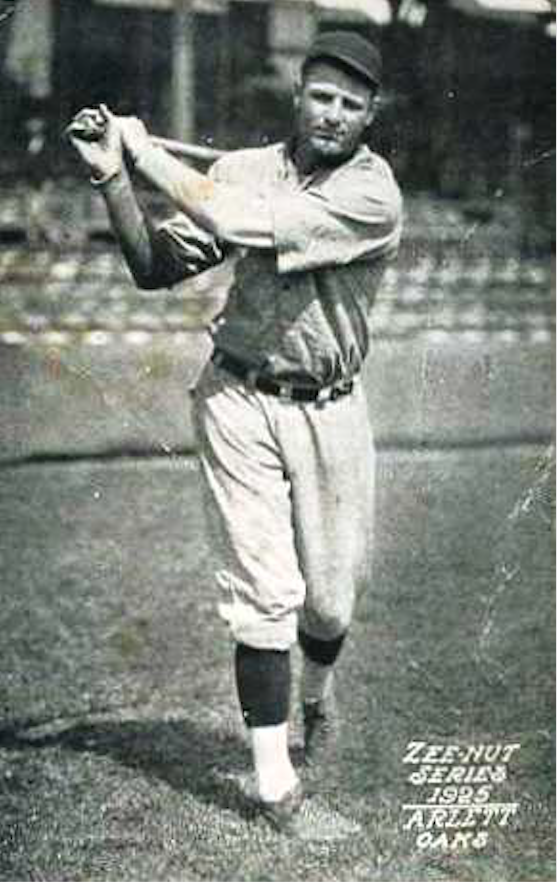

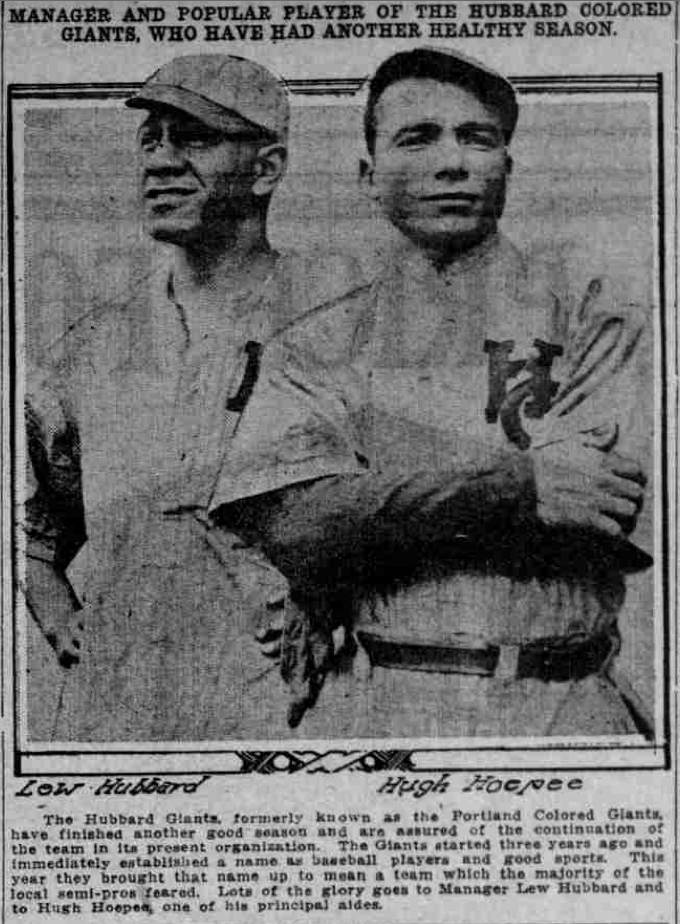

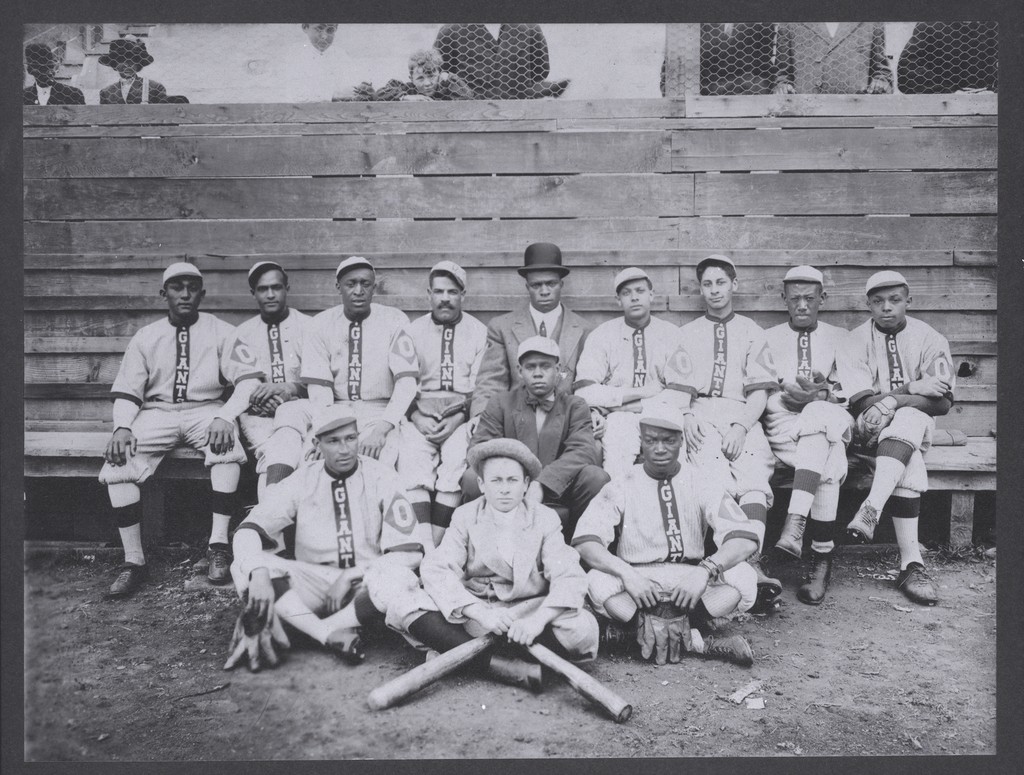

Some of the Trilbys last years were spent barnstorming in Northern California after they could no longer access games in Southern California against teams of stature. Years later, during the 1920’s in the city of Los Angeles, William H. Carroll and James M. Alexander decided to join forces once again to create the Alexander Giants of Los Angeles. By the time Carrol and Alexander founded the Alexander Giant, Carroll was the owner of a grocery store. James M. Alexander continued to work for J.W. Robinson for close to a decade, eventually moving into the position as an elevator operator. After Alexander left the ‘dry goods’ business, he worked for the U.S. Dept. of the Interior as a “stamp deputy”. Prior to being a tax stamp man, Alexander was a “Revenuer”. In the 1940’s he became a real estate broker. It would seem that the silent partner in the early Trilbys was also a businessman, even if Carroll was the outspoken front man, making them a perfect pair, both on and off the field of play.

Many great players came from the Alexander Giants. William H. Carroll and James Alexander had been connected to Los Angeles baseball twenty-five years before they ever thought about establishing the Alexander Giants. They were the Trilby men of Los Angeles first.

1) O’Neal Pullen

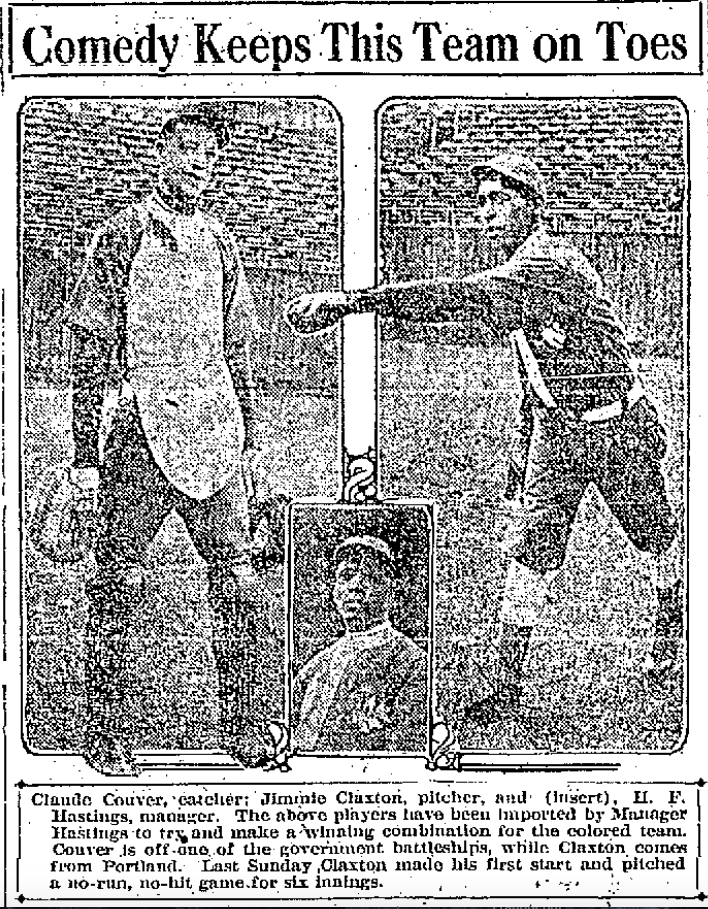

2) Jimmy Claxton

3) Harry Blackmon

4) Hilary “Bullet” Meaddows

5) Carlisle Perry

6) Goldie Davis

7) William Ross

8) George Henry “Tank” Carr

Which leads us to understand that no African American baseball team, like the Alexander Giants can ever be created out of thin air. That some African American team owners have a deep rooted history in the game of baseball — and may have at one time played the game as well.

And that every baseball team has a bridge to their origin story.

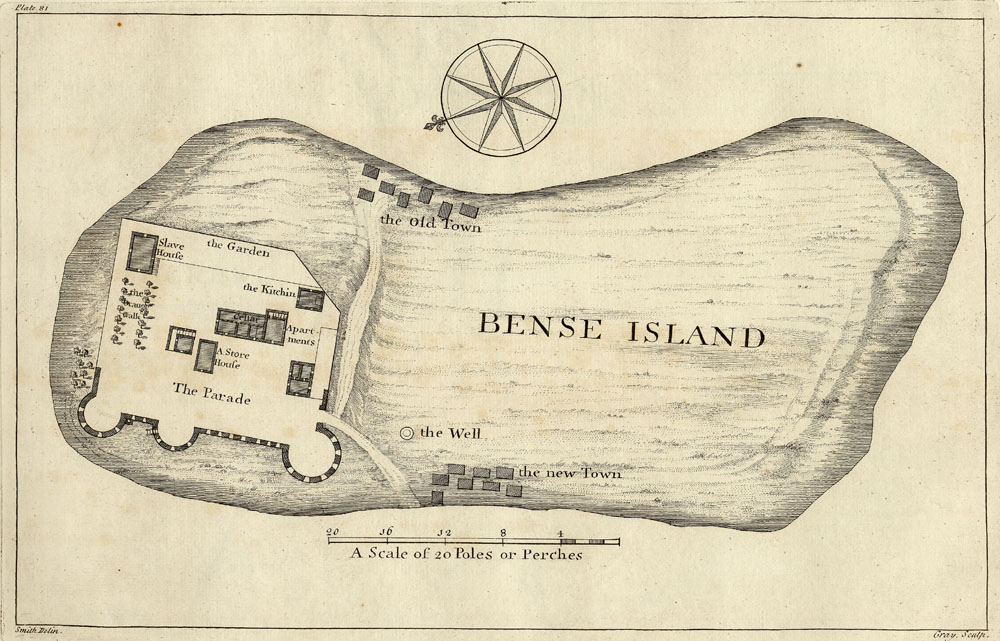

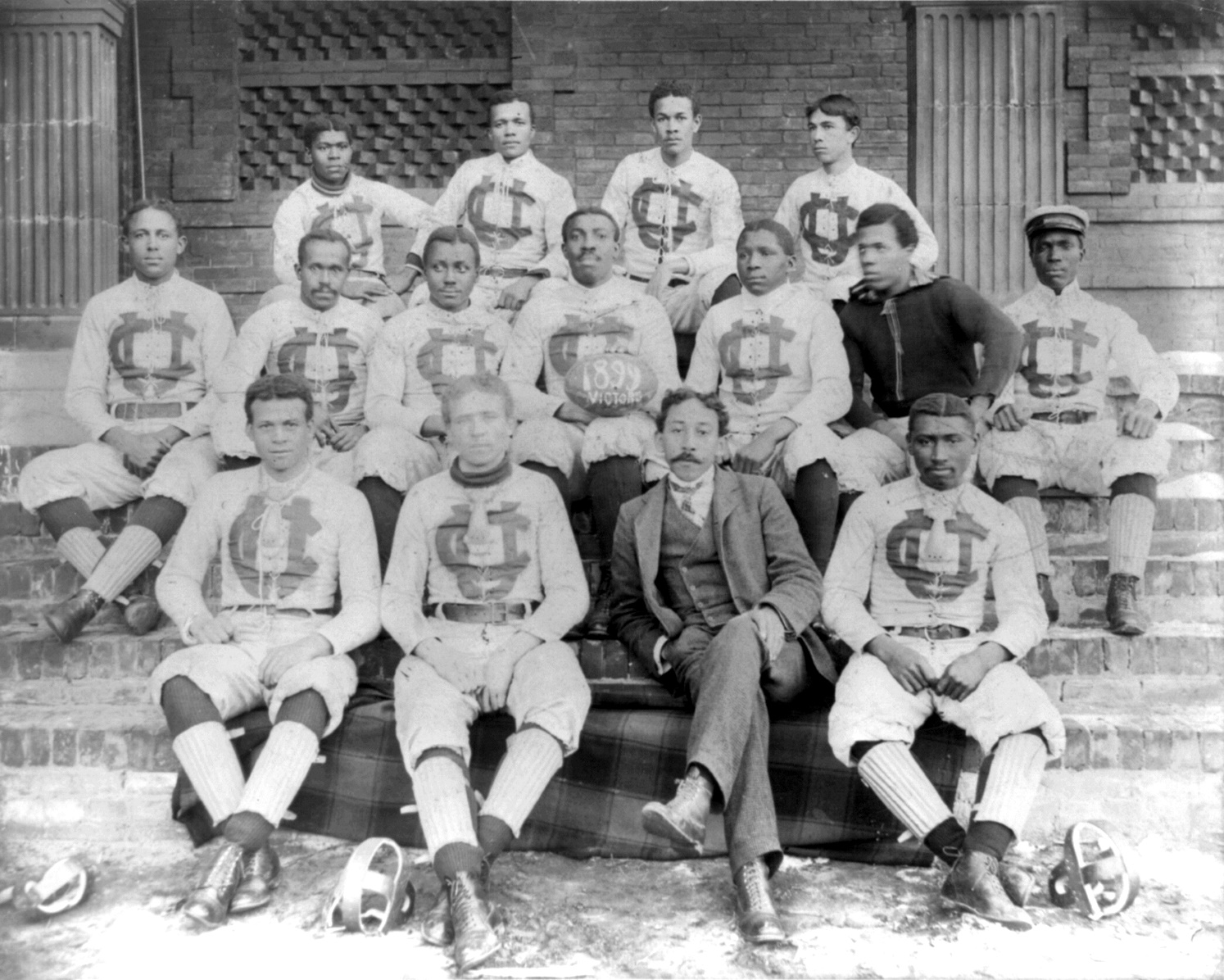

Bance Island — in Tagrin Bay, Sierra Leone

Bance Island — in Tagrin Bay, Sierra Leone

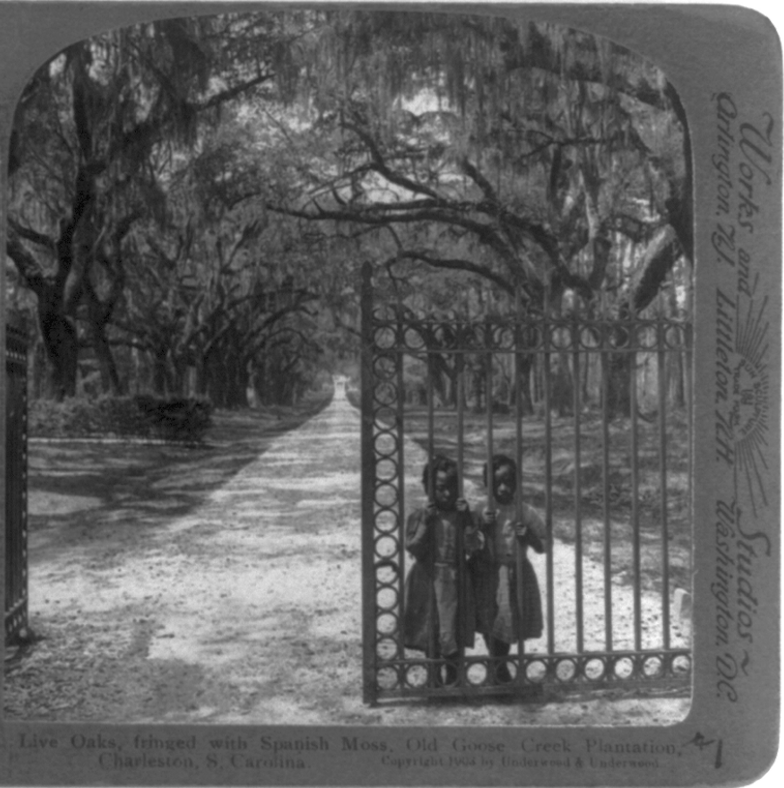

The Wedge Plantation House – circa 1923 (Charleston County)- courtesy of the Georgetown County Library.

The Wedge Plantation House – circa 1923 (Charleston County)- courtesy of the Georgetown County Library.

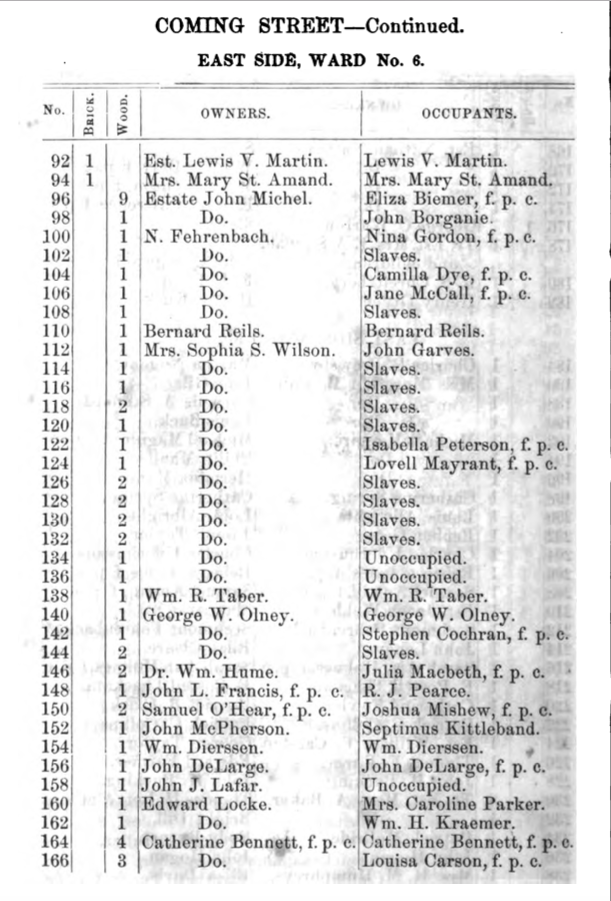

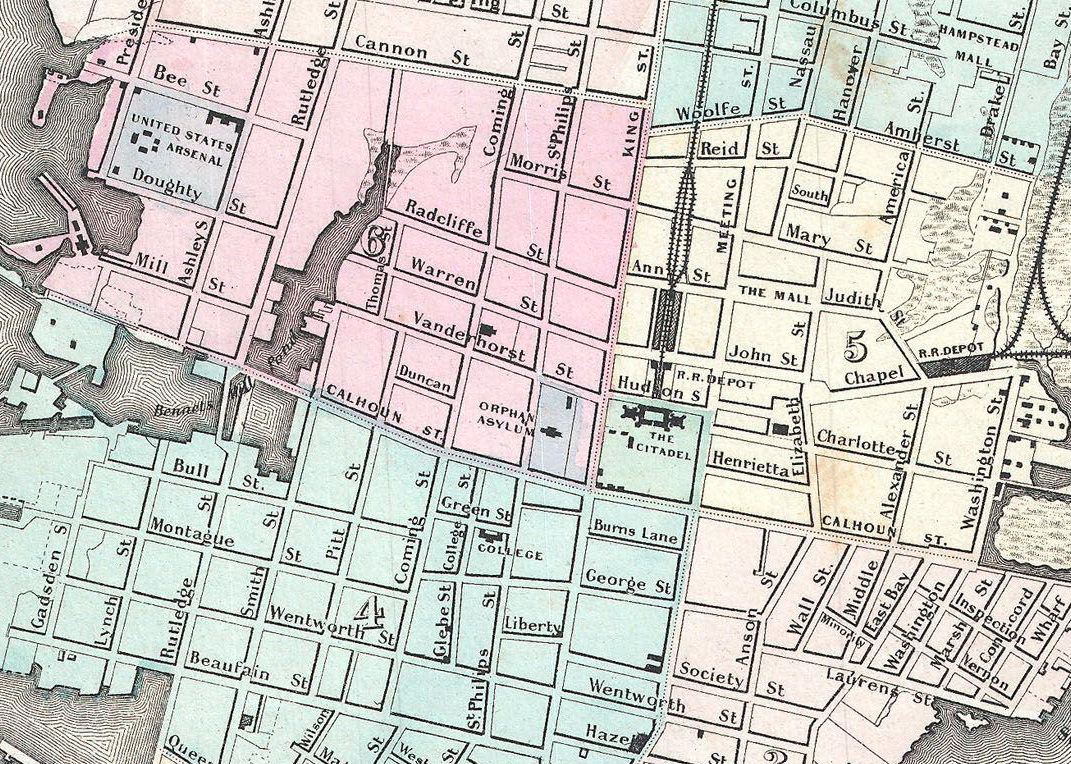

146 Comings Street to Marion Square

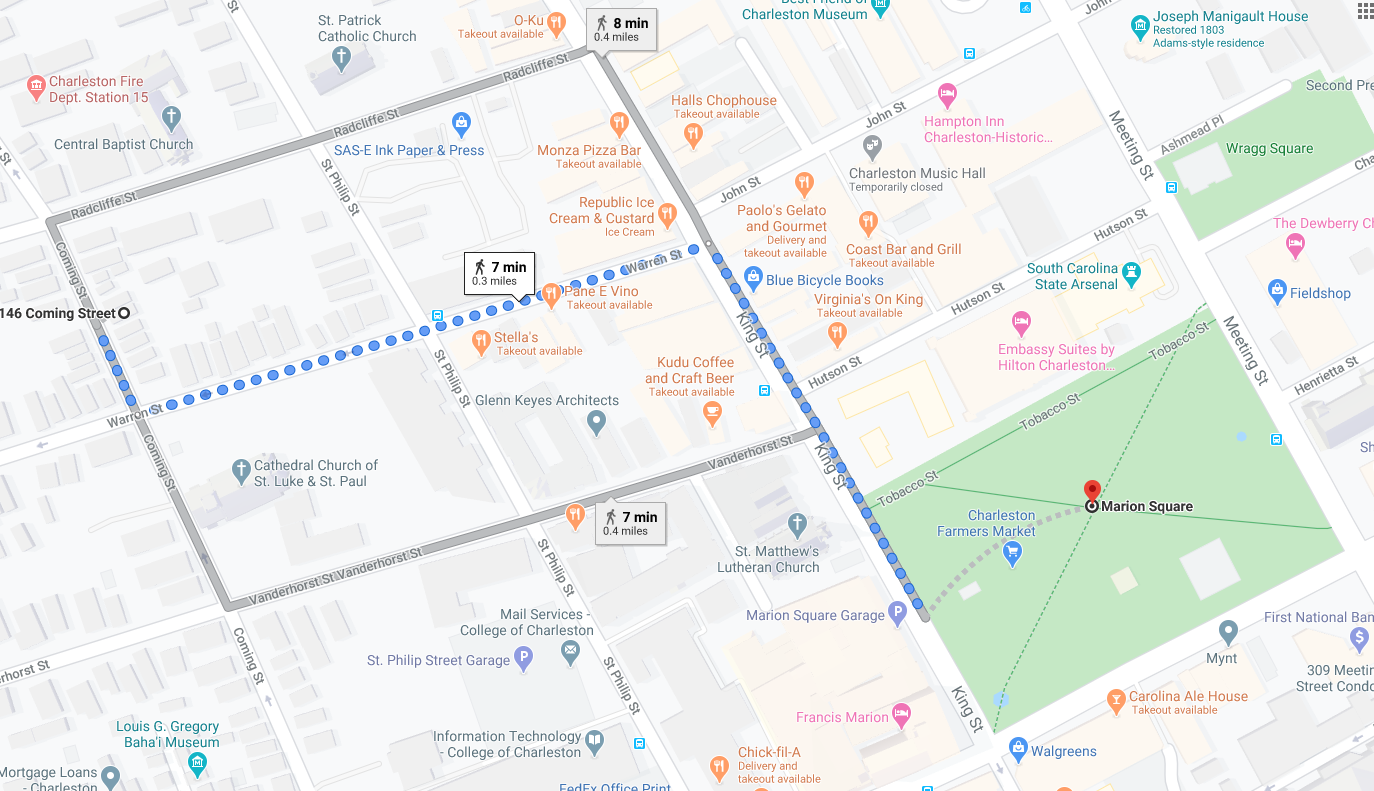

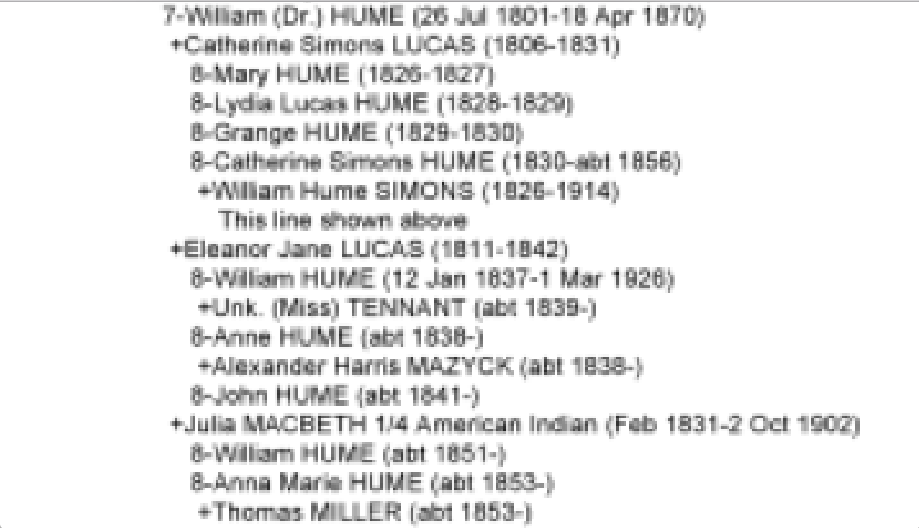

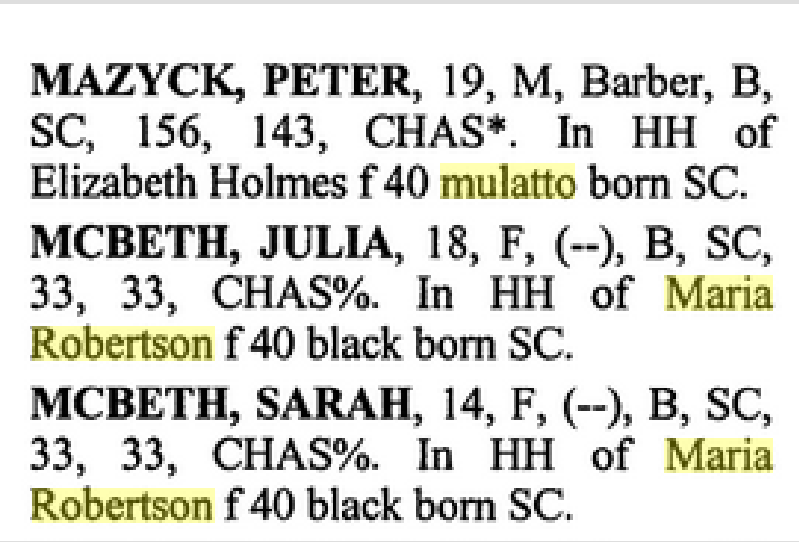

146 Comings Street to Marion Square Julia Macbeth – U.S. 1880 Census Record showing, No. 146 Comings Street – son Edward, daughter Martha, and Julia’s mother, Anna “Maria” Roberson.

Julia Macbeth – U.S. 1880 Census Record showing, No. 146 Comings Street – son Edward, daughter Martha, and Julia’s mother, Anna “Maria” Roberson. Slavery Distribution Chart – 1861 U.S. Census, Department of Interior

Slavery Distribution Chart – 1861 U.S. Census, Department of Interior The Negro Population – by Walter Wilcox, population chart, pg. 23,

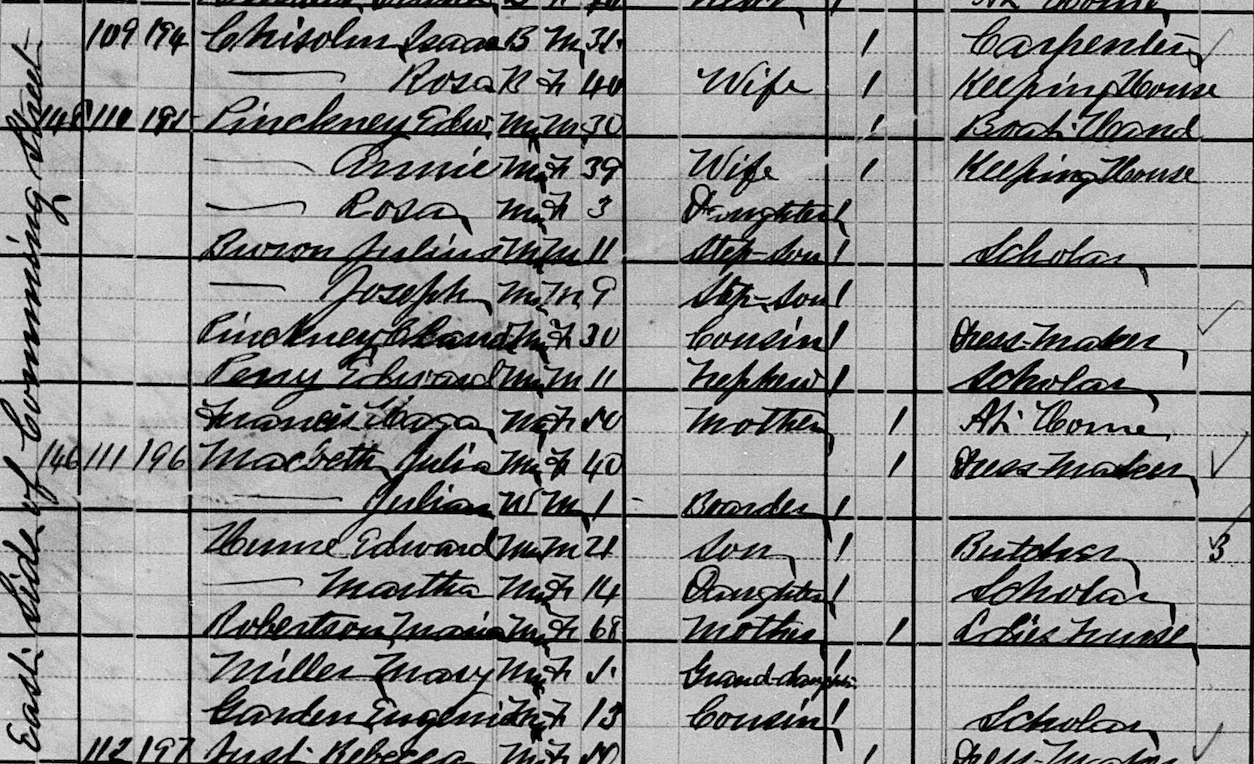

The Negro Population – by Walter Wilcox, population chart, pg. 23,  Claflin University Football Team -1899

Claflin University Football Team -1899

Thomas E. Miller – with the Masonry Class – 1896-1898 -Bradham Hall, South Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical Institute.

Thomas E. Miller – with the Masonry Class – 1896-1898 -Bradham Hall, South Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical Institute.

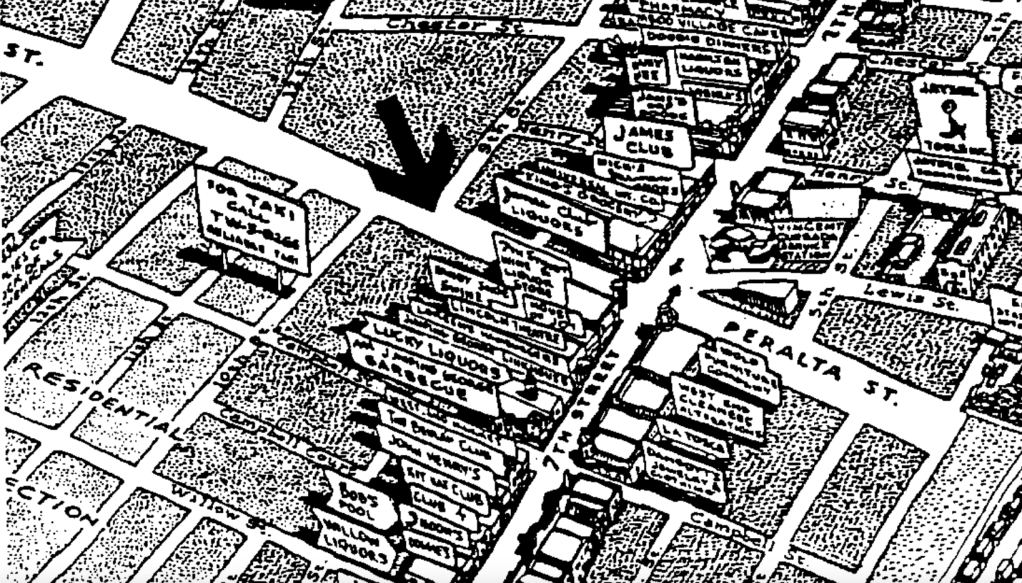

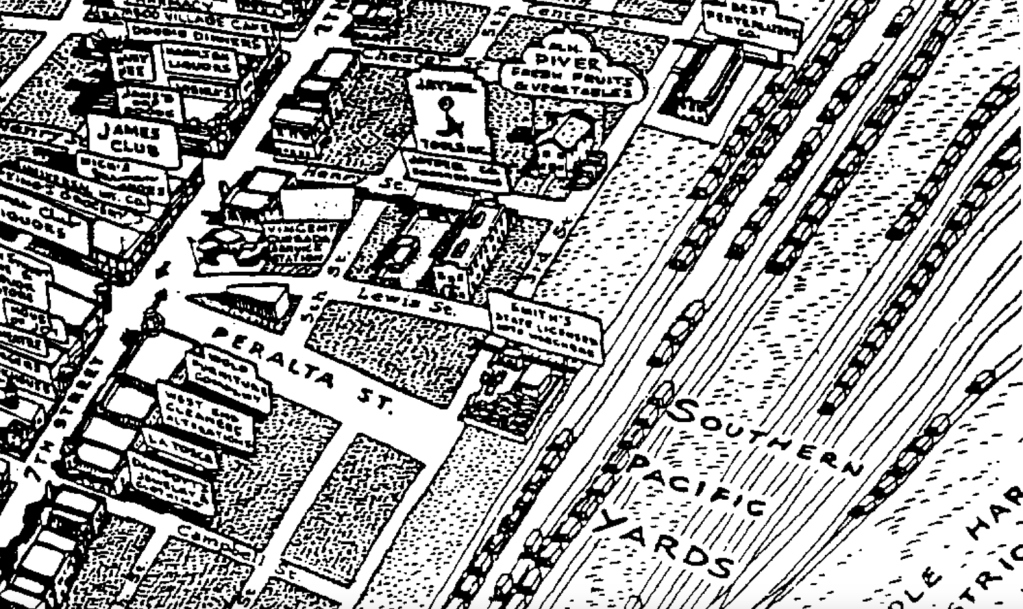

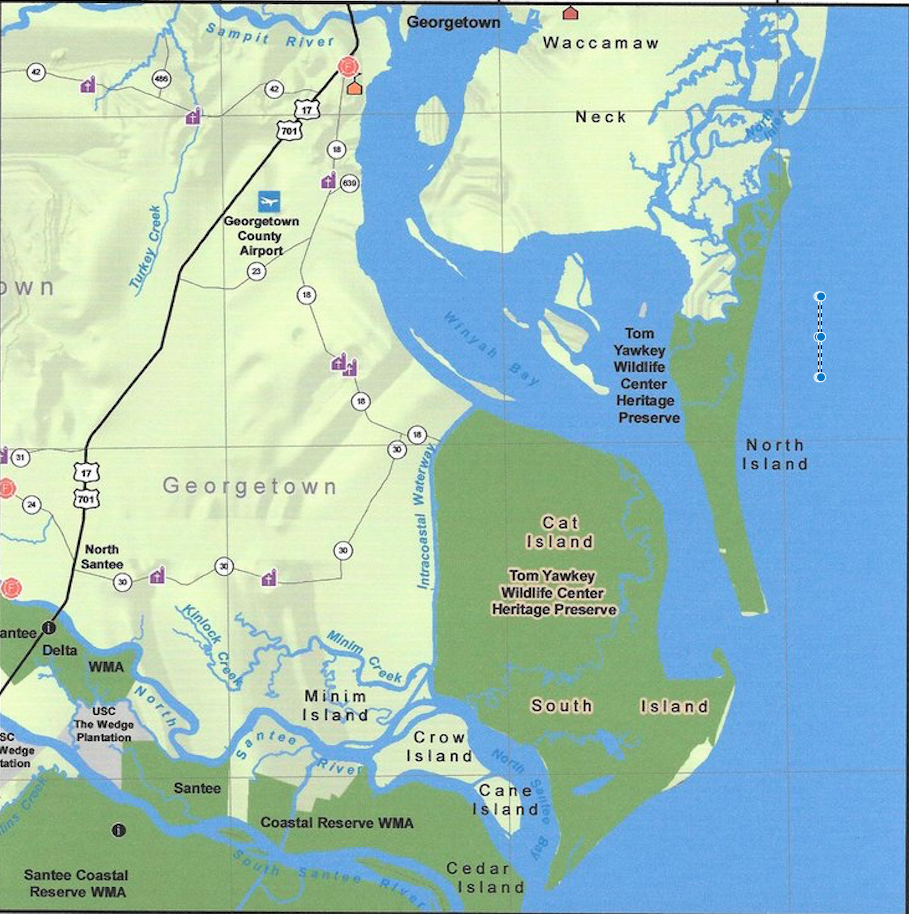

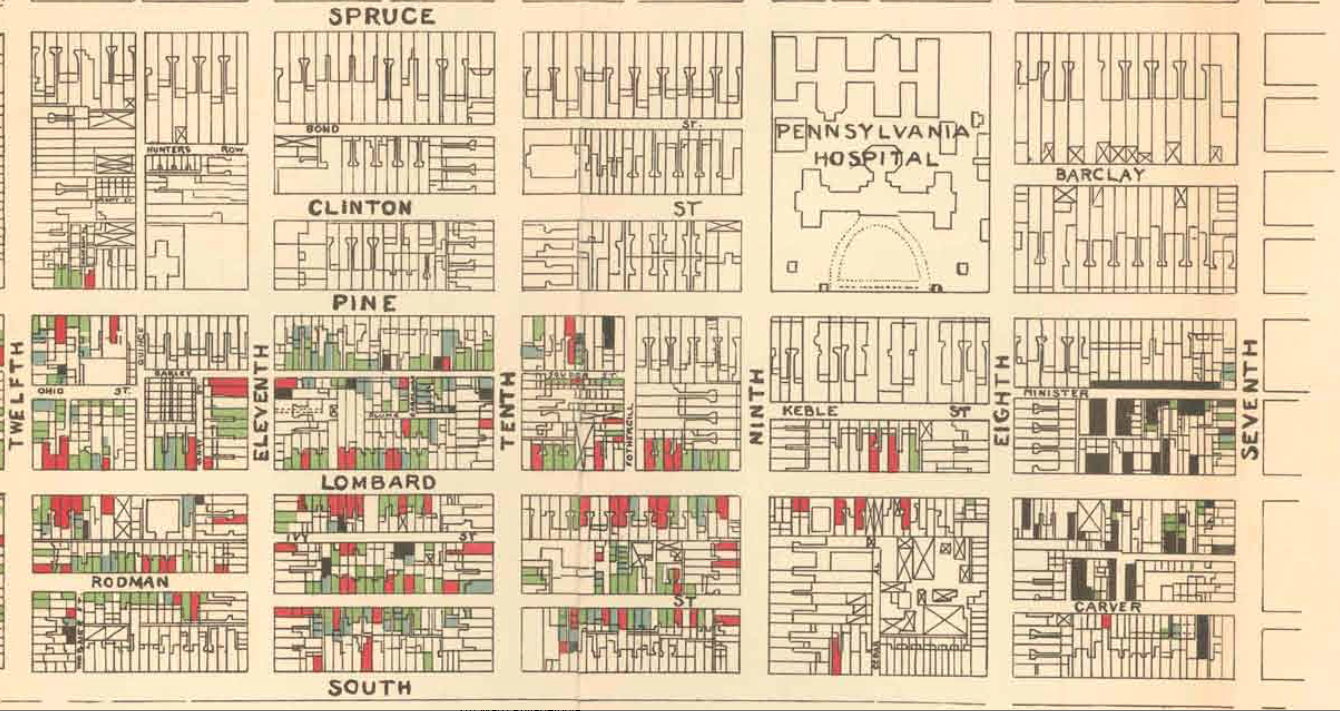

Map of a portion of the “7th Ward” – “

Map of a portion of the “7th Ward” – “

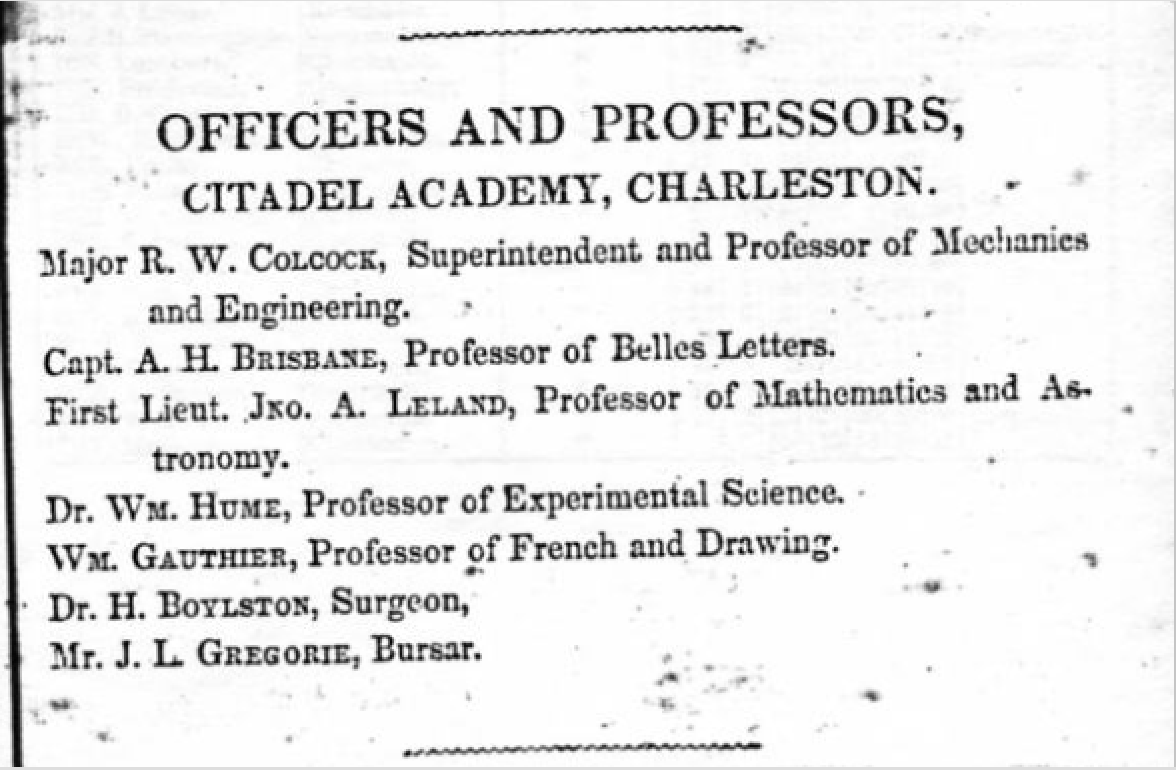

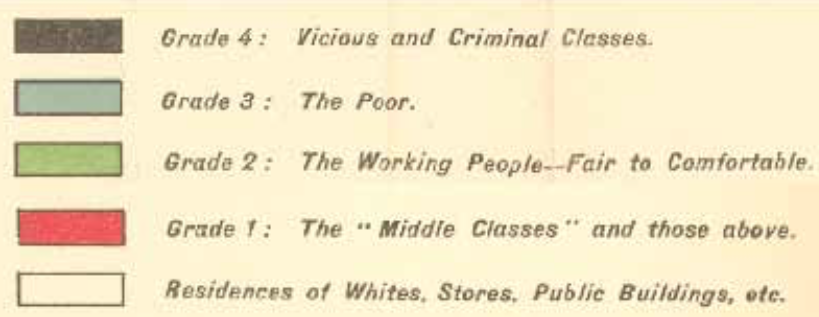

“The History And Life Of Octavius V. Catto, And Trial Of Frank Kelly”, compiled by Henry H Griffin, pg.6

“The History And Life Of Octavius V. Catto, And Trial Of Frank Kelly”, compiled by Henry H Griffin, pg.6

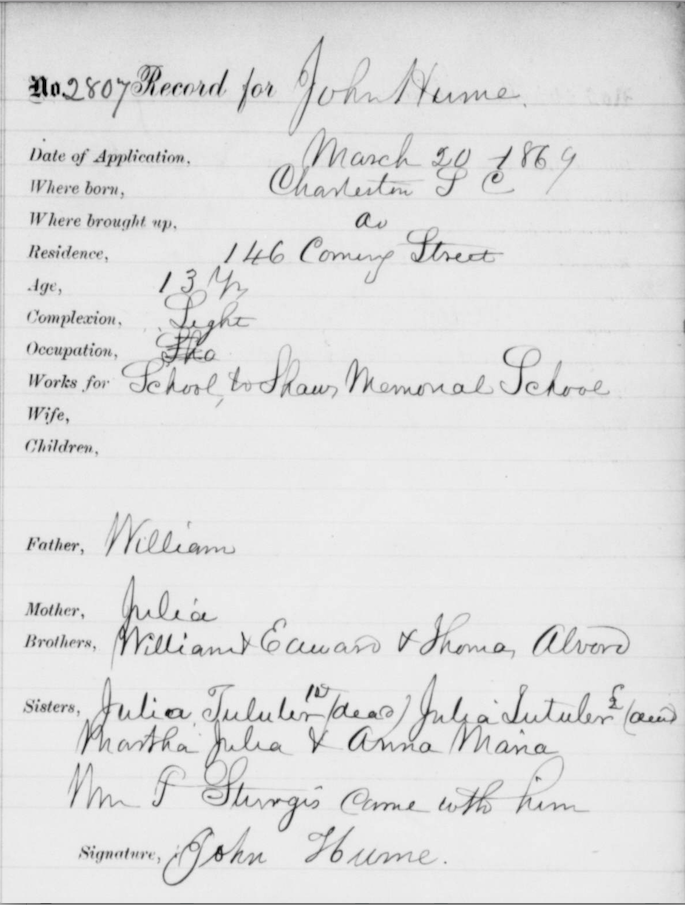

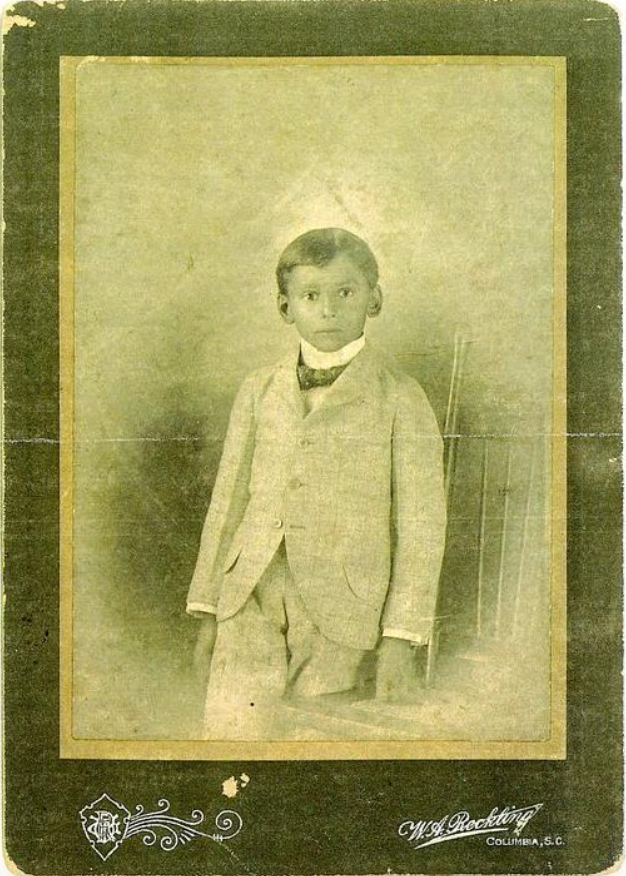

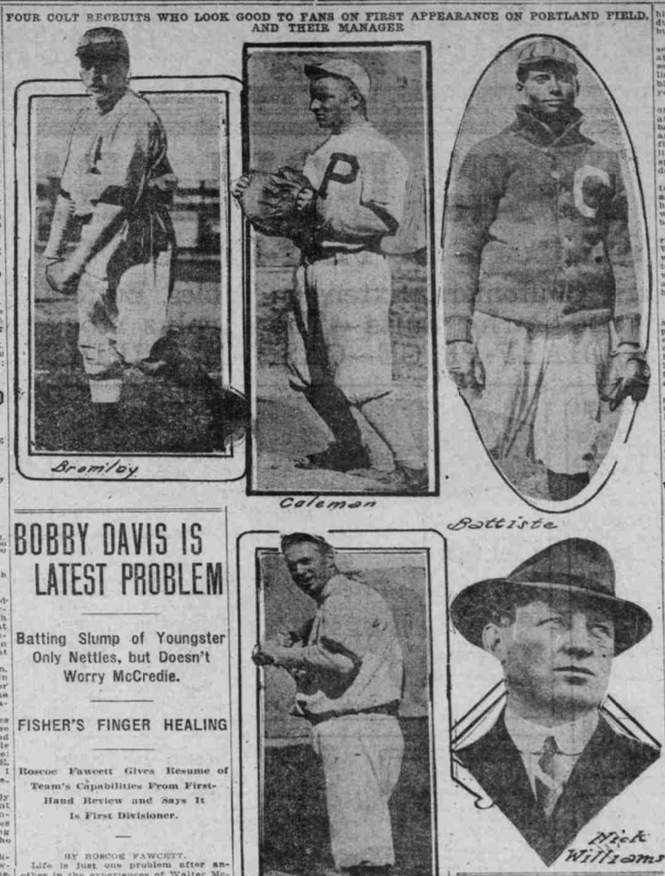

Hume L. Battiste – school records – ‘Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf and Dumb‘

Hume L. Battiste – school records – ‘Pennsylvania Institution for the Deaf and Dumb‘

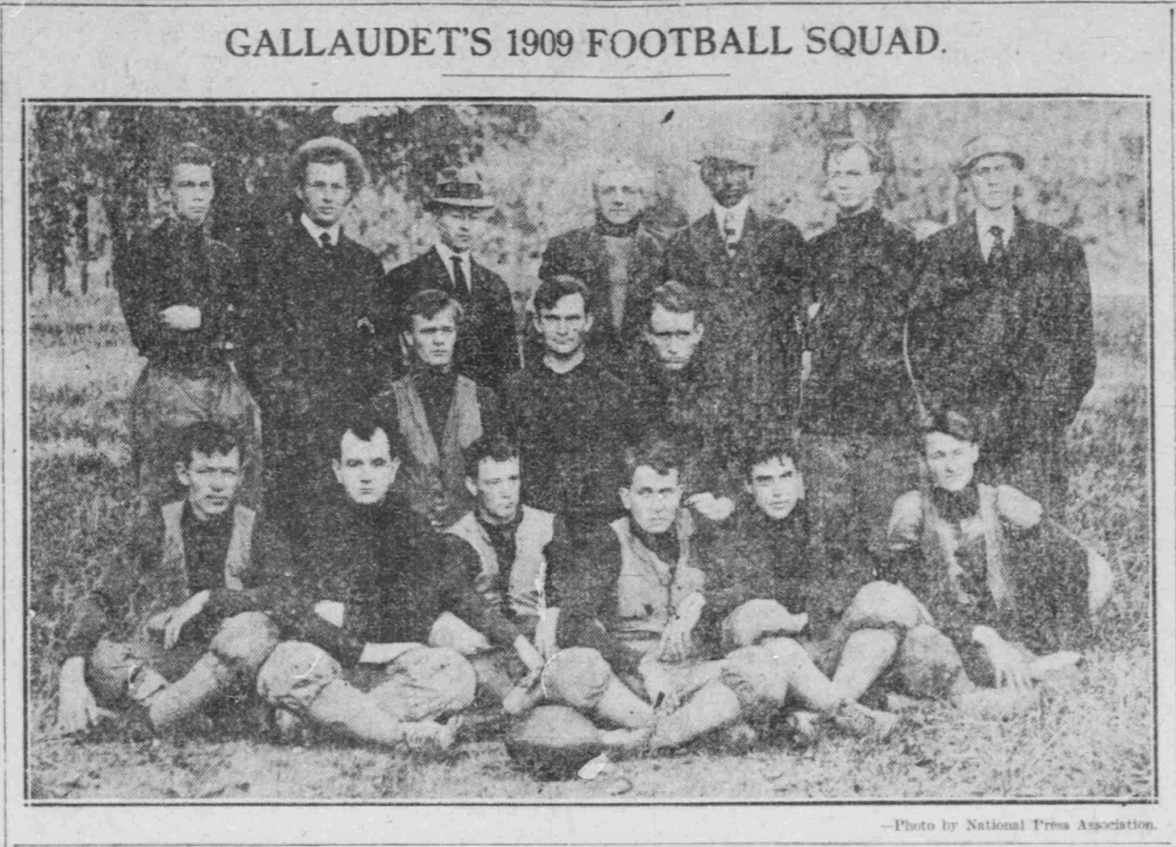

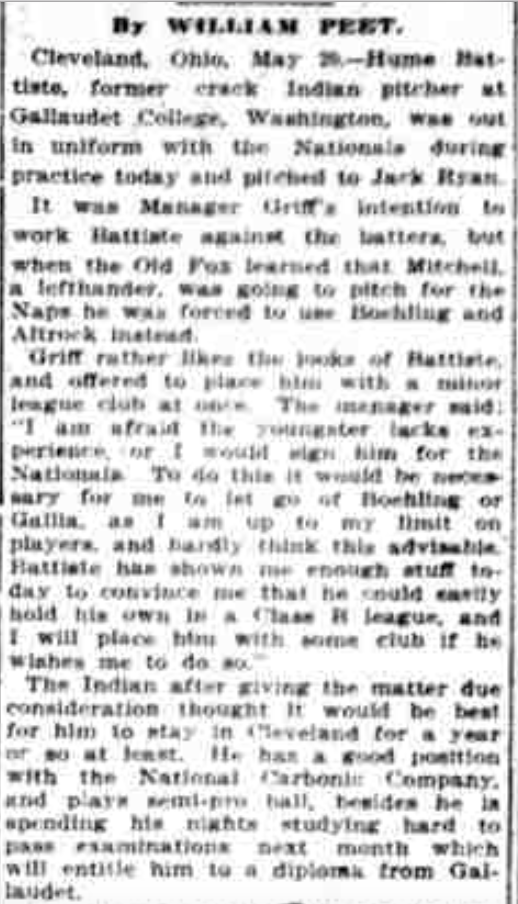

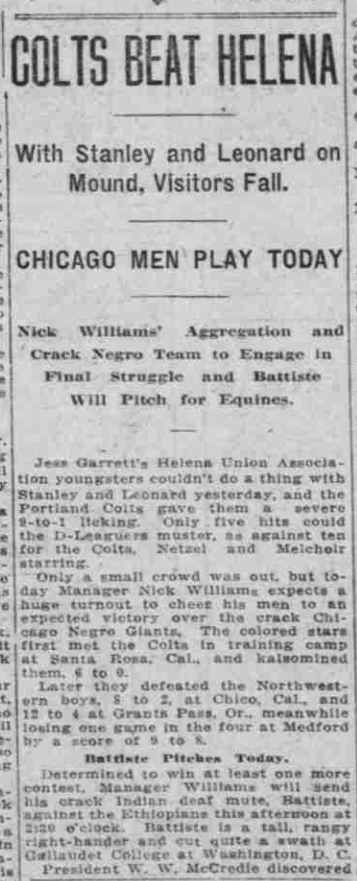

The Washington Herald – March 14, 1909

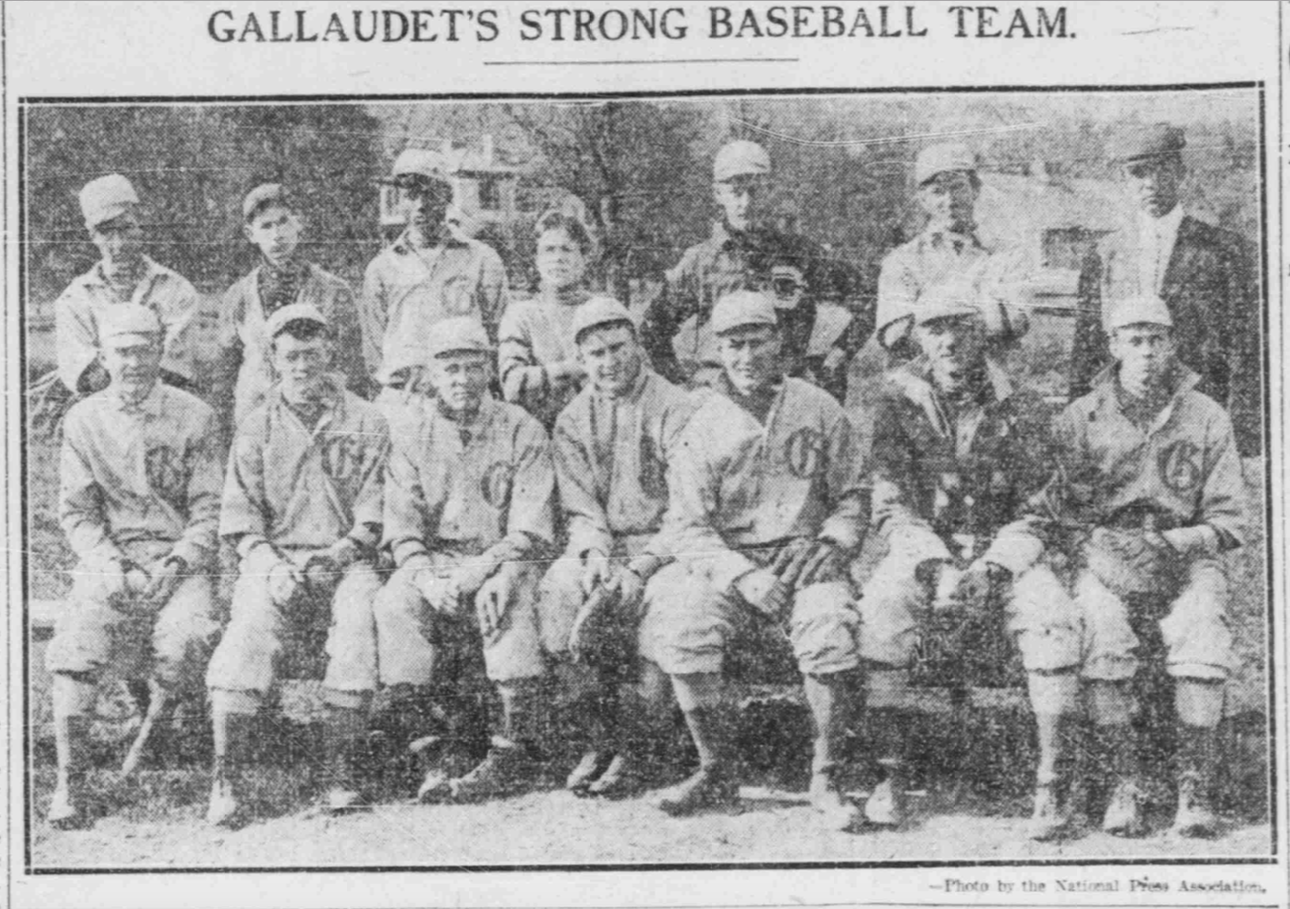

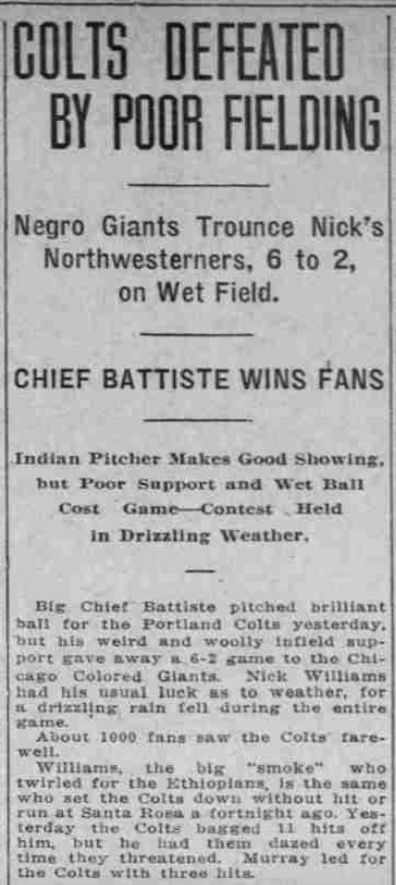

The Washington Herald – March 14, 1909 Left to Right: Battiste, Unknown, Vernon “Cotton” Birck – Gallaudet Bisons Baseall 1912

Left to Right: Battiste, Unknown, Vernon “Cotton” Birck – Gallaudet Bisons Baseall 1912

Gallaudet College Catalogue, 1909-1910

Gallaudet College Catalogue, 1909-1910

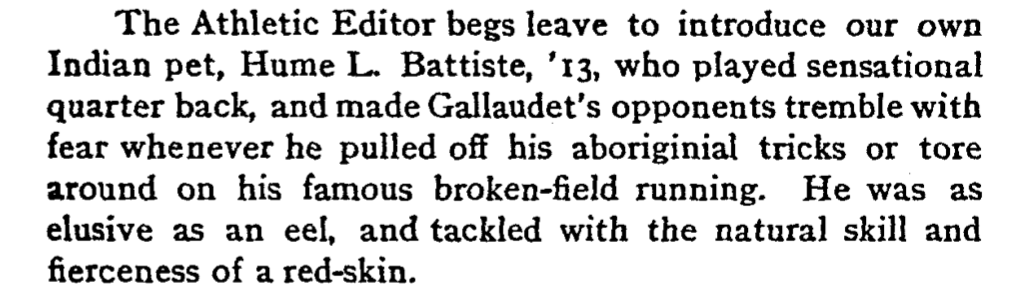

1911 Football – courtesy of Gallaudet University Archives.

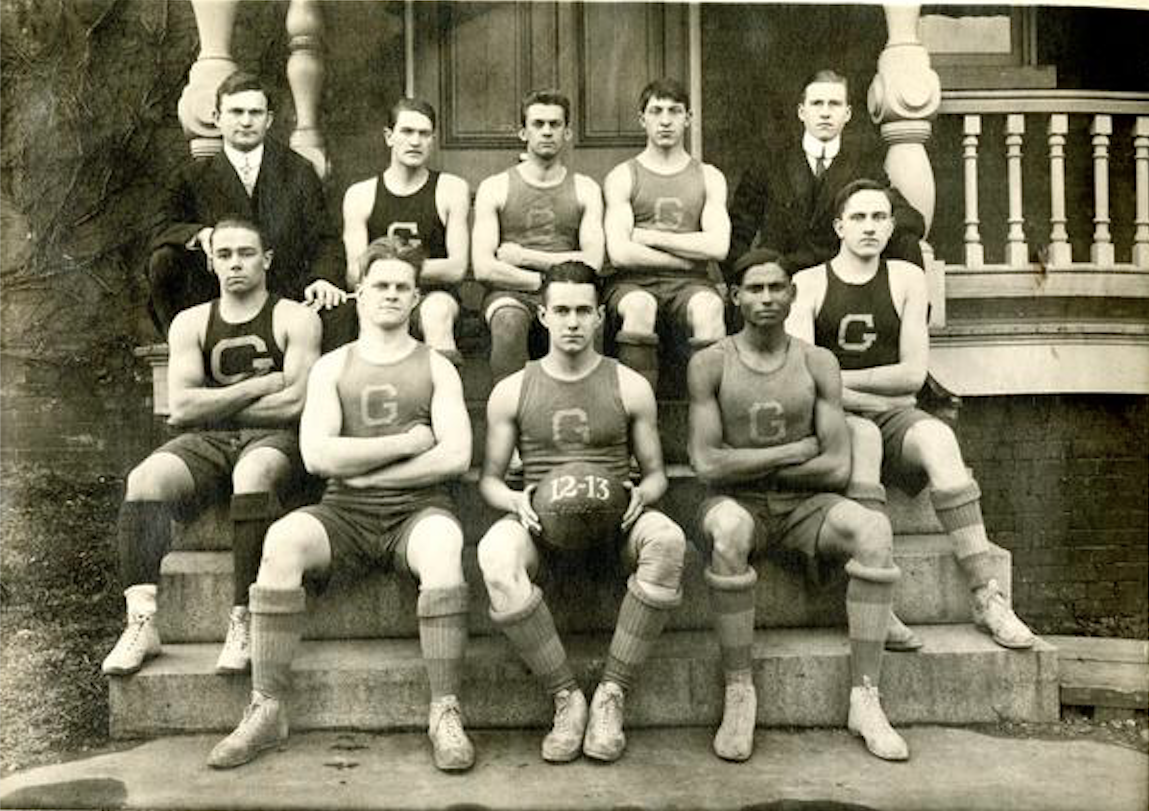

1911 Football – courtesy of Gallaudet University Archives. 1912-1913 Fives – courtesy of Gallaudet University Archives

1912-1913 Fives – courtesy of Gallaudet University Archives

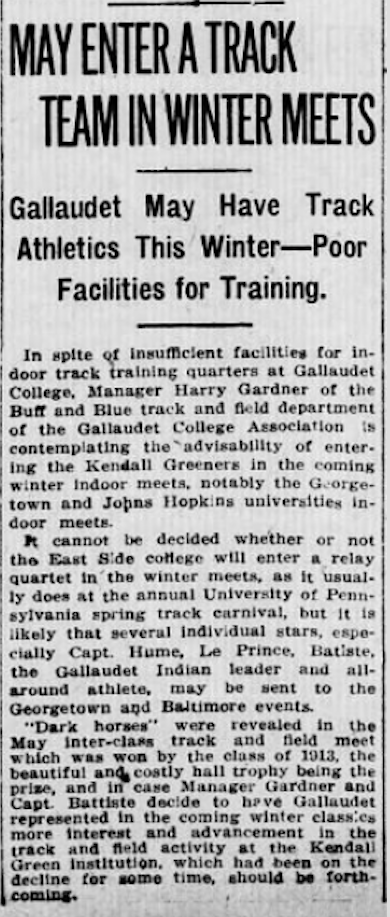

The Washington Herald – October 17, 1909

The Washington Herald – October 17, 1909

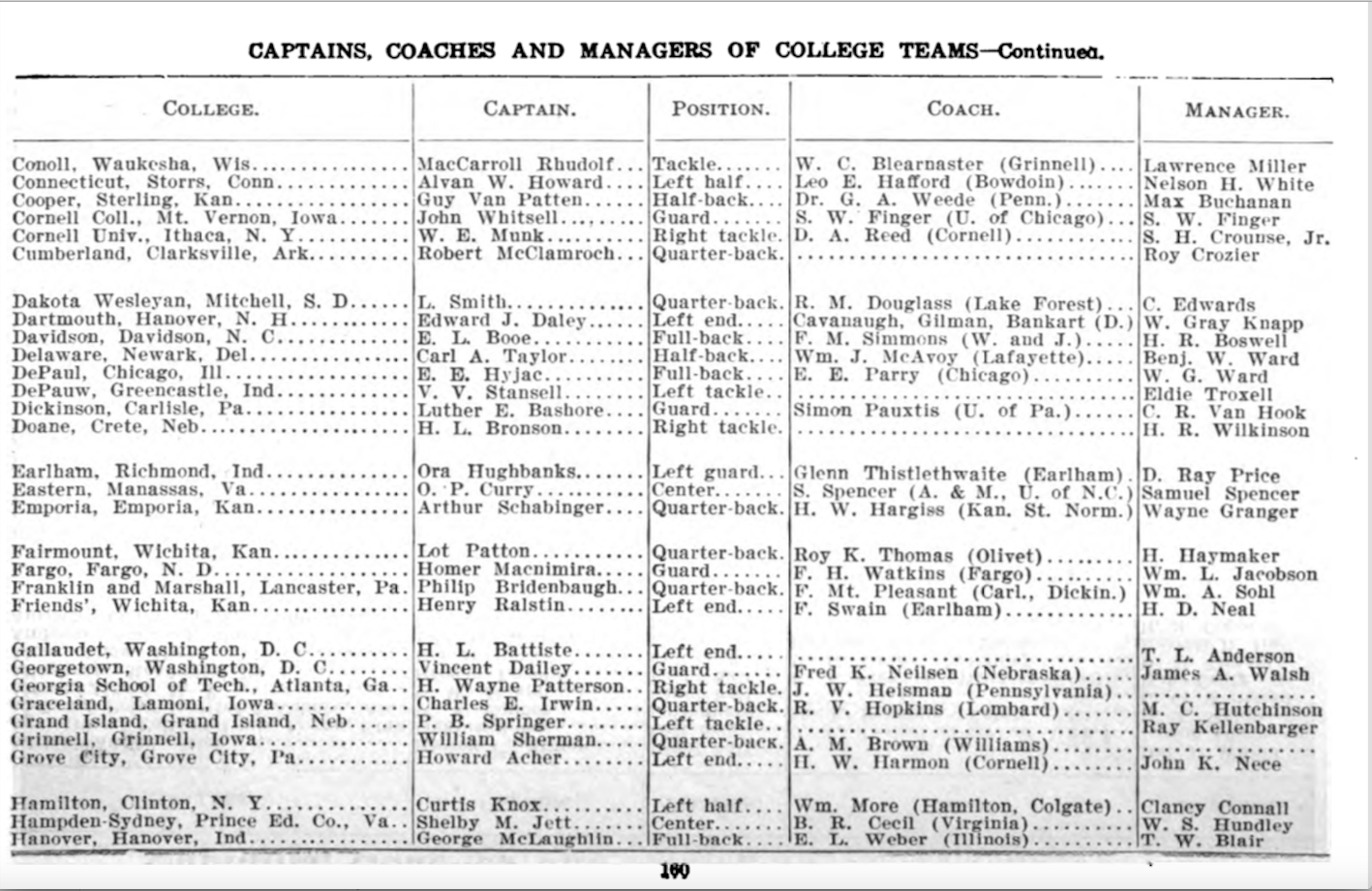

The Official National Collegiate Athletic Association Football Guide – 1911, pg. 160

The Official National Collegiate Athletic Association Football Guide – 1911, pg. 160

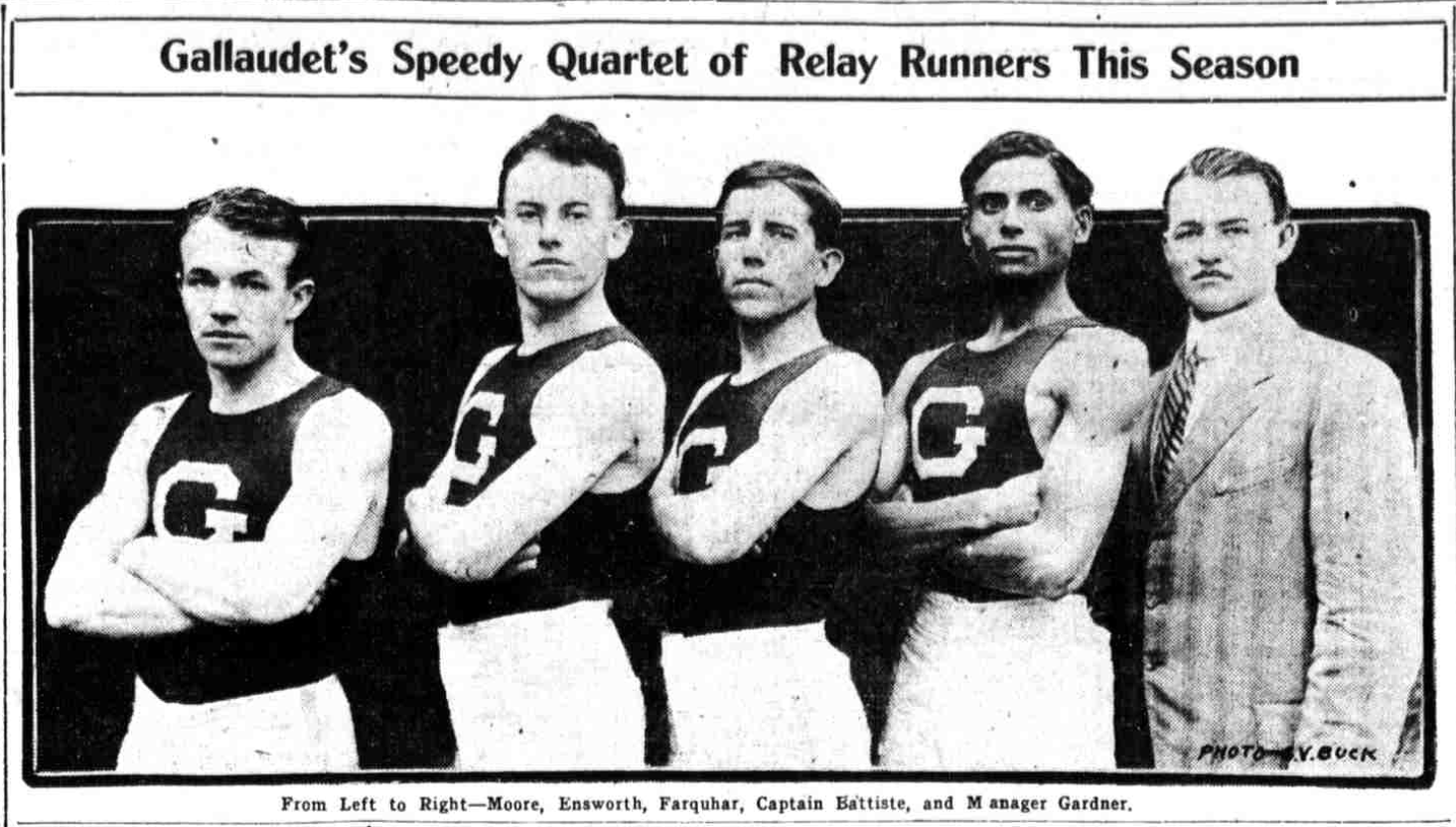

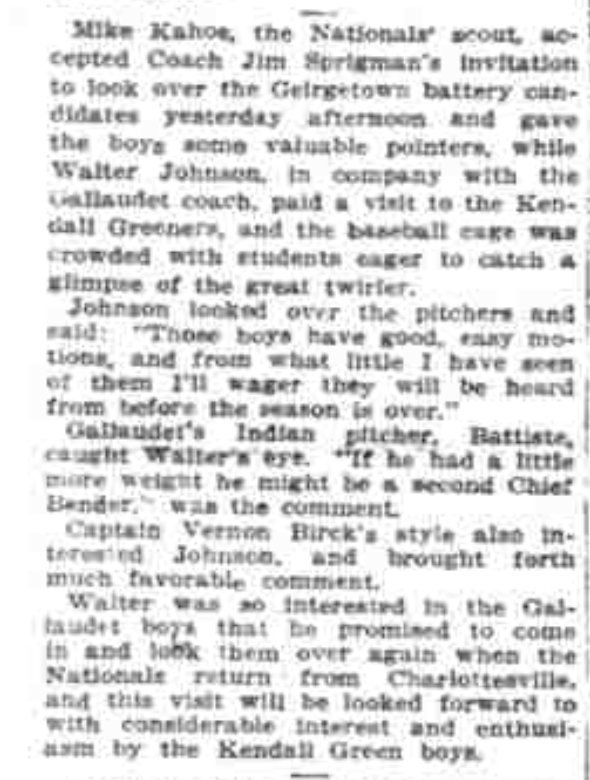

The Evening Star – March 28, 1912

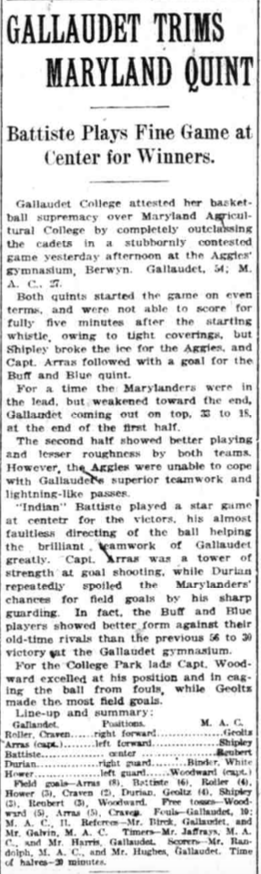

The Evening Star – March 28, 1912 The Washington Herald – March 07, 1913

The Washington Herald – March 07, 1913 The Washington Herald – March 09, 1913

The Washington Herald – March 09, 1913 The Washington Herald – May 11, 1913

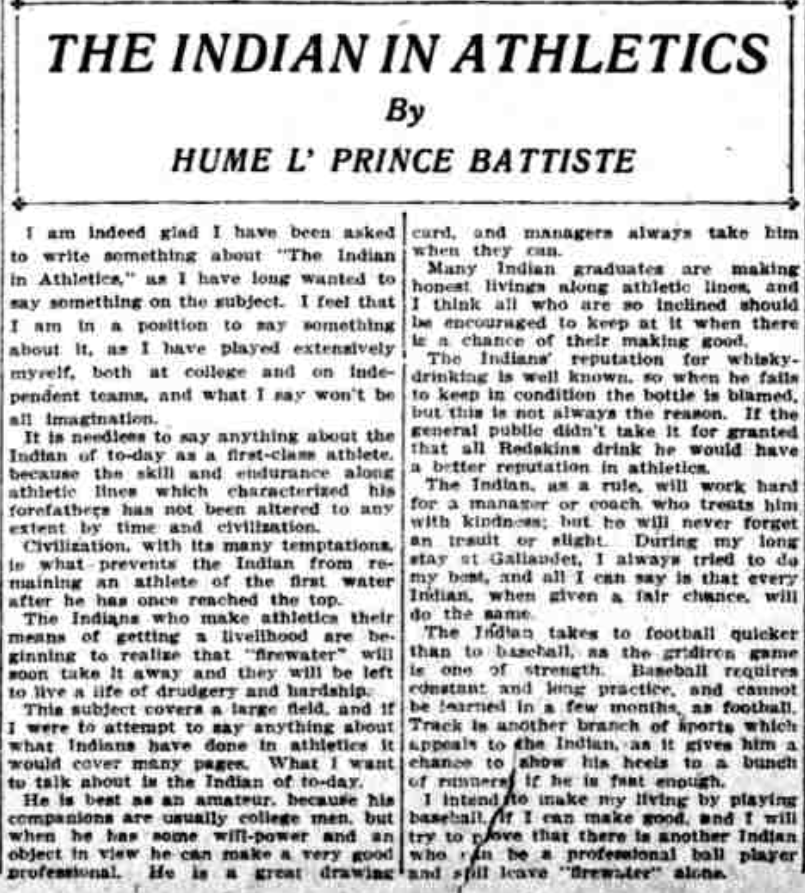

The Washington Herald – May 11, 1913

The Washington Herald – July 16, 1913.

The Washington Herald – July 16, 1913. Sporting Life – March 21, 1914

Sporting Life – March 21, 1914

The Silent Worker – Vol. 34, No. 9, June 1922

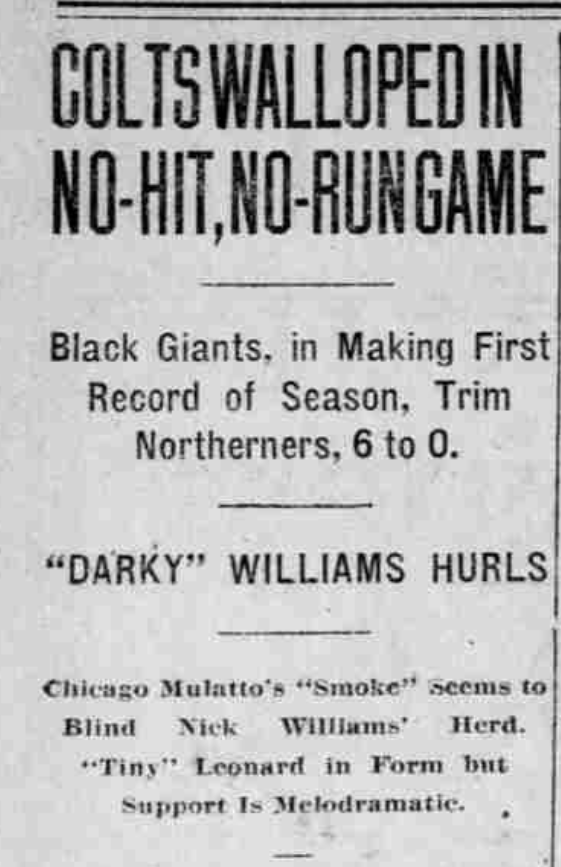

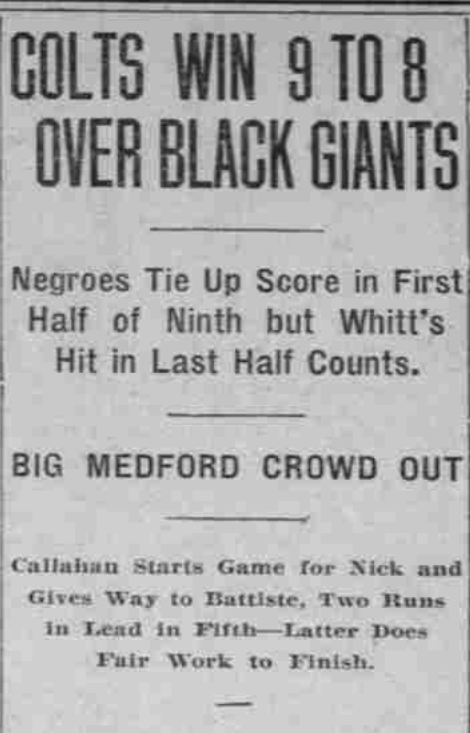

The Silent Worker – Vol. 34, No. 9, June 1922 The Oregon Daily Journal – March 31, 1914

The Oregon Daily Journal – March 31, 1914

Hume Le Prince Battiste – U.S. Census 1930

Hume Le Prince Battiste – U.S. Census 1930 Hume Le Prince Battiste – U.S. Census 1940

Hume Le Prince Battiste – U.S. Census 1940

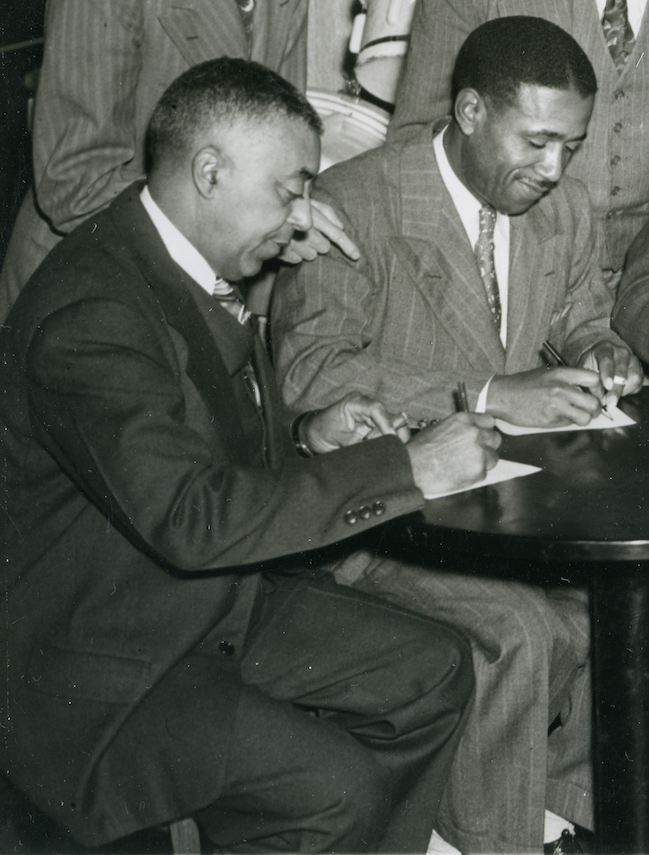

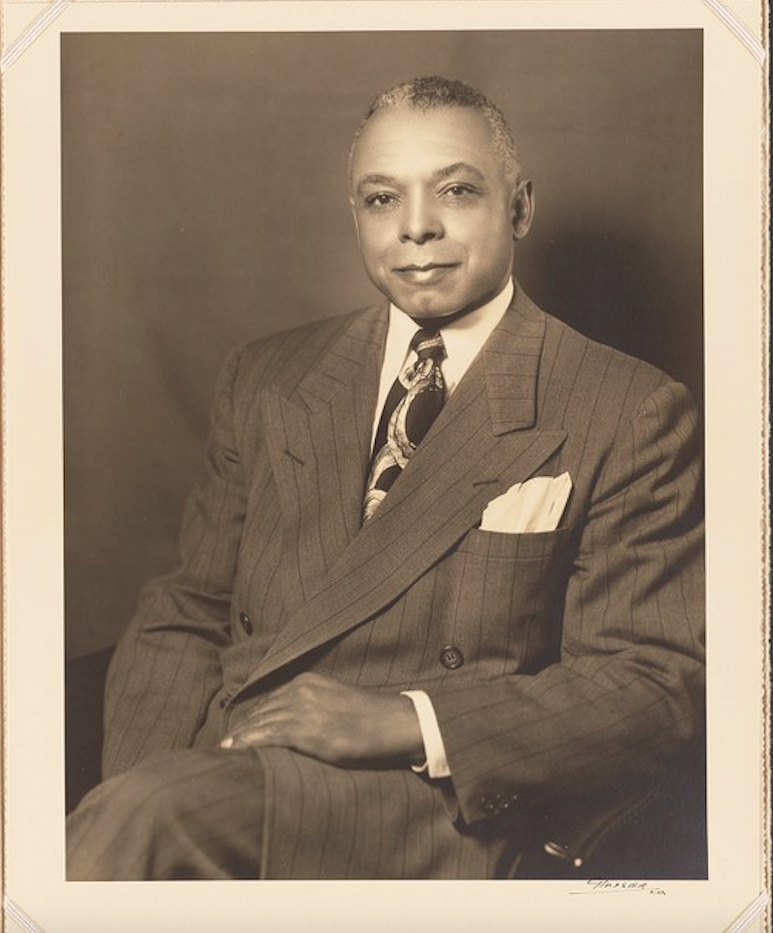

Congressman Andrew Young and Norman O. Houston (UCLA, Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library)

Congressman Andrew Young and Norman O. Houston (UCLA, Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library)

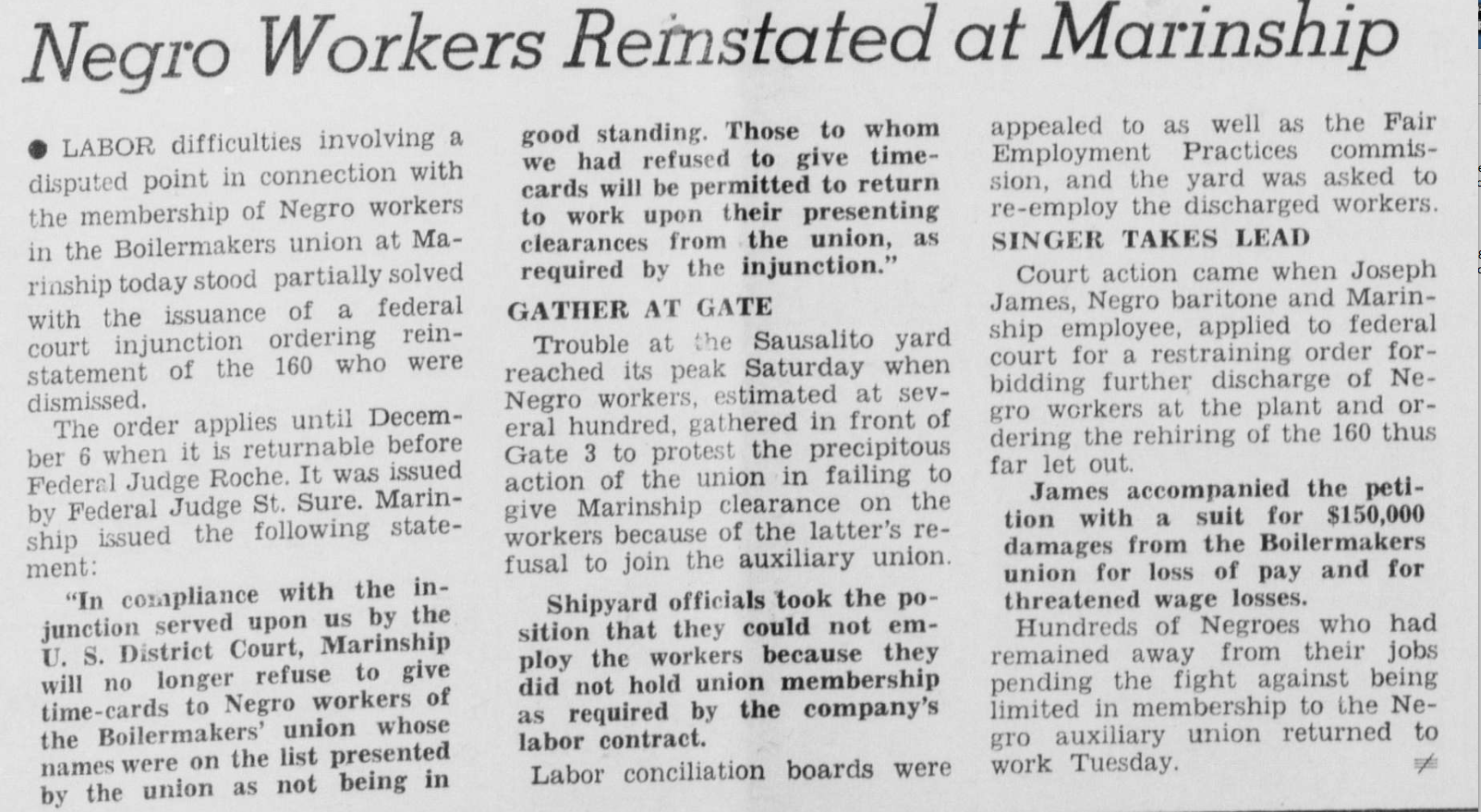

![Boilermakers A26 baseball team; [E.F. Joseph collection, Careth Reid; Sports]](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/boilermakers-a-26-team-1942.jpg) A-26 Boilermakers, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (

A-26 Boilermakers, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (

![Boilermakers A26 baseball team; [E.F. Joseph collection, Careth Reid; Sports]](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/boilermakers-a-26-team-pitcher-mike-show-boat-berry.jpg)

![Boilermakers A26 baseball team; [E.F. Joseph collection, Careth Reid; Sports]](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/boilermakers-a-26-team-willie-tat-mays-bunting.jpg)

![Boilermakers A26 baseball team; [E.F. Joseph collection, Careth Reid; Sports]](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/boilermakers-a-26-team-theodore-teddy-cabe-catching.jpg)