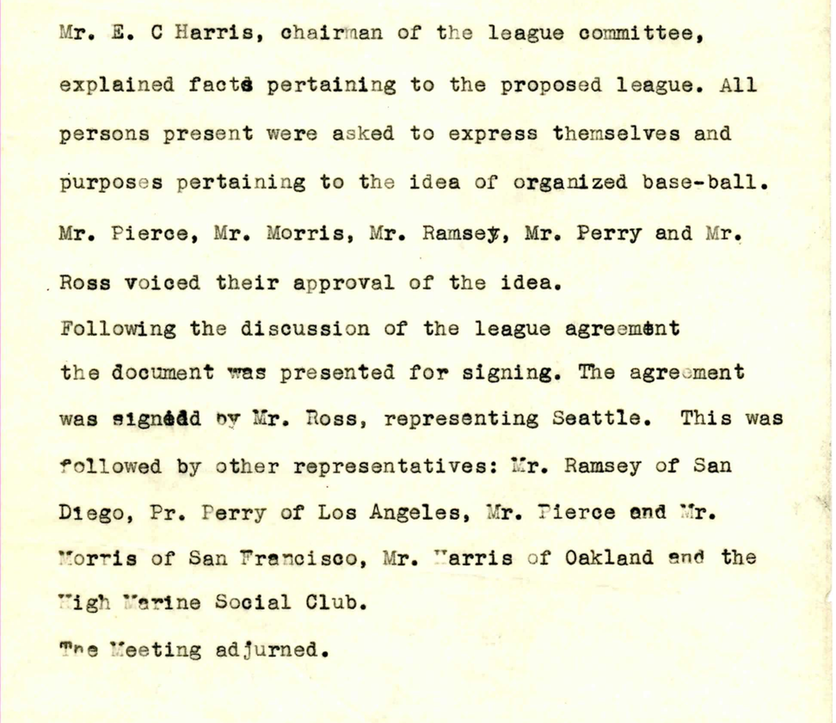

When the Oakland High Marine Club met on October 18, 1945, a three day meeting took place between interested parties, who would set in motion the creation of the “West Coast Baseball Association“. Time was of the essence. This idea had been tossed around for some time, and it was time to put it in writing, striking the beginnings of a formal agreement between African American businessmen of the West Oakland and South Berkeley Communities about creating a Negro League they could call their own.

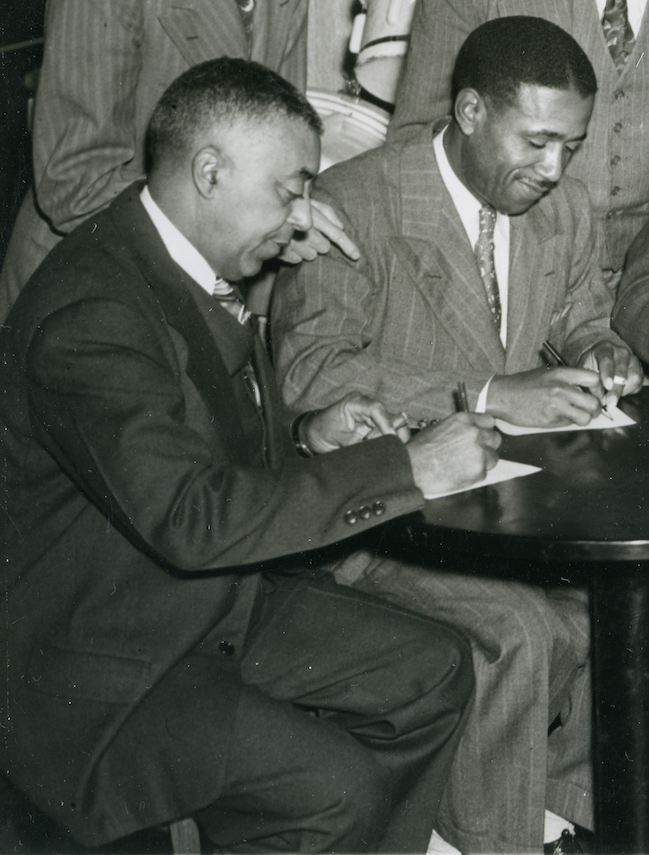

Earlier in the year, on August 28, 1945, Branch Rickey had signed Jackie Robinson to a contract to play in the minor leagues with the Montreal Royals. This formative move created tension on the other side of the color fence of what was to come of the Negro Leagues. It sent shock waves through the West Oakland’s and South Berkeley’s African American communities, and many other African American communities across the nation, where the face of the National Pastime was about to change permanently.

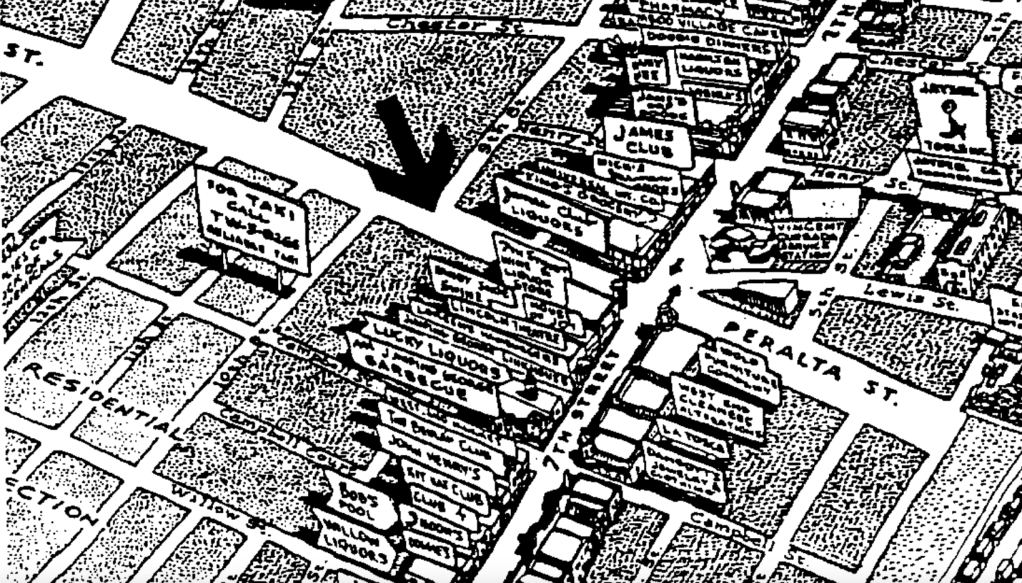

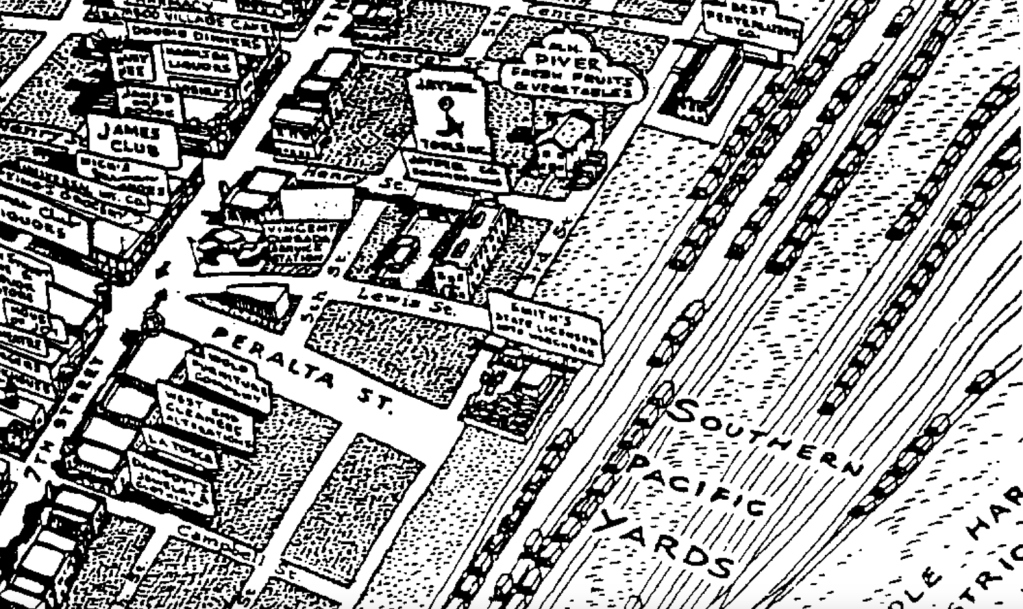

West Oakland after all, was the Harlem of the West, and 7th Street played an integral part in the nation’s African American vibrant culture and race climate, that help foster African American baseball and businesses coast to coast. They also supported the Negro Leagues both far and wide in every aspect of the game. Oakland, being the last stop for the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters across the nation, was the mecca of the West for information about African American communities and culture changes that took place, from all over the United States.

For better or for worse, there would be no stopping the future desegregation of Major League Baseball. And the collective Bay Area needed to prepare for the overarching economic outcome that this proposed ‘integration’ move, and how it would change the economic and political landscape. How would the possibility of the desegregation of professional baseball impact the African American community at at large? This was the question on the minds of local African American business owners, and it certainly needed to be addressed.

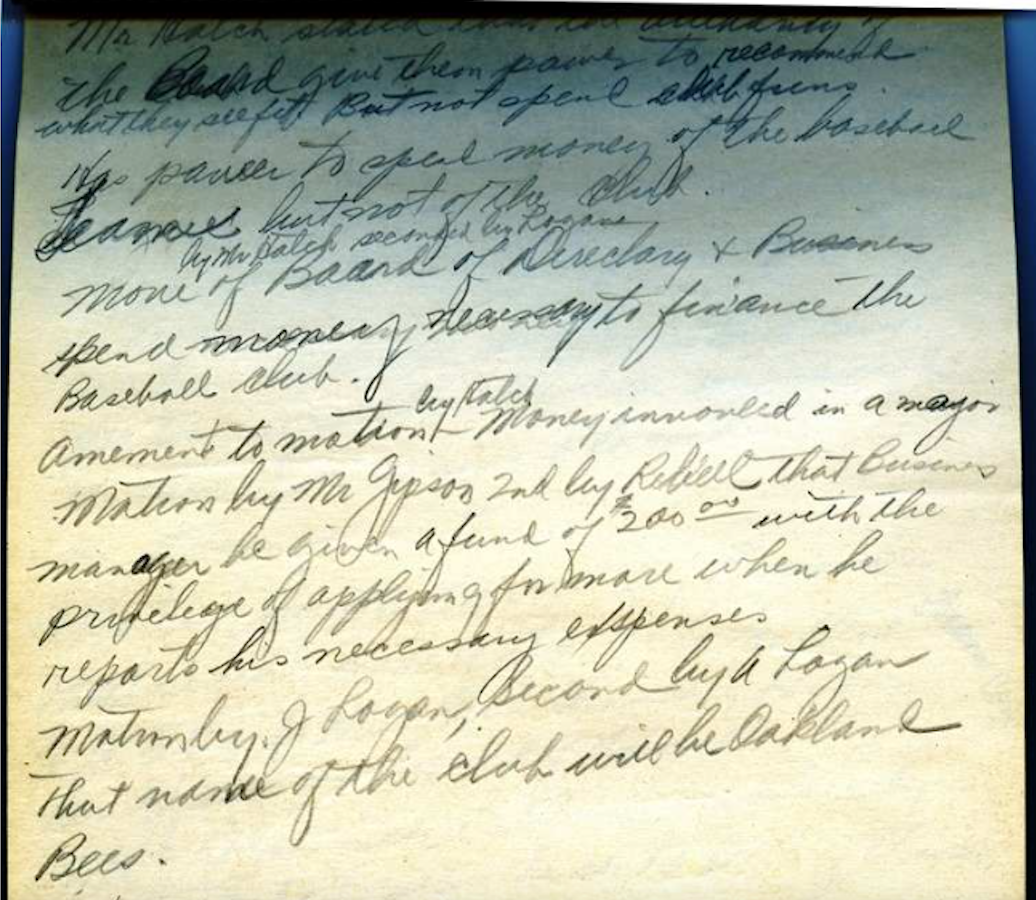

The first mention of a ‘West Coast’ Negro League was brought up at a meeting of the Oakland High Marine Club on July 12, 1945, when it was noted by the Secretary of that organization, that a small group had a round tabled a discussion about a proposal made by Ed C. Harris, that had to do with “Baseball”. The first pitch for this idea was tossed out by Harris, who had played semi-pro ball for the California Eagles. The idea of mounting a ‘West Coast’ Negro League began weeks before Robinson signed an agreement with Rickey, and sooner than later, the creation of the West Coast Baseball Association would become more than simple table talk.

By August 8, 1945, twenty days before Jackie Robinson would sign a contract to play with Montreal, the Oakland High Marine Club would put together a fact finding committee, with Harris in charge, to study the feasibility of starting a brand new West Coast Negro League, in anticipation that the current Negro Leagues would see a mass exodus of players lost to desegregation of the Major Leagues. The other consideration was finding untapped talent from returning African America soldiers, who would soon be coming home from the Pacific and European theaters.

In hopes that this would be a new beginning for those who wanted to maintain financially independence of Major League Baseball, which had rejected African Americans since its inception based on an unwritten rule among players, coaches, the front office and owners, — the Oakland High Marine Club set forth on the road to insure an alternative pathway for the African America professional baseball players, coaches, managers, and team owners was put in play.

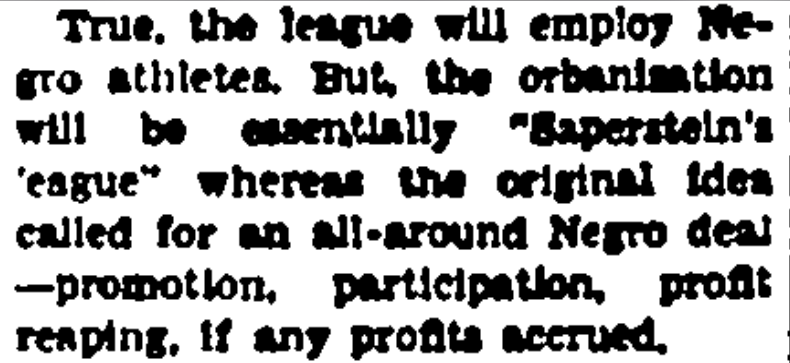

How Abe Saperstein and Jesse Owens became a part of the West Coast ‘Baseball’ Association is a complete mystery, because there is no indication of their involvement at all in the Summer of 1945, when the first seeds of this new league were planted. There is only an indication that Saperstein’s involvement happened sometime late in January 1946. The concept of Saperstein becoming the President of the West Coast Baseball Association, along with his Vice President and associate, Jesse Owens, is completely separate story in and of itself, — which very little research has yet to be performed on that particular subject matter. The fact remains though, both Saperstein and Owens were not a part of the original group of men that decided that the West Coast needed or deserved its own professional Negro League representation.

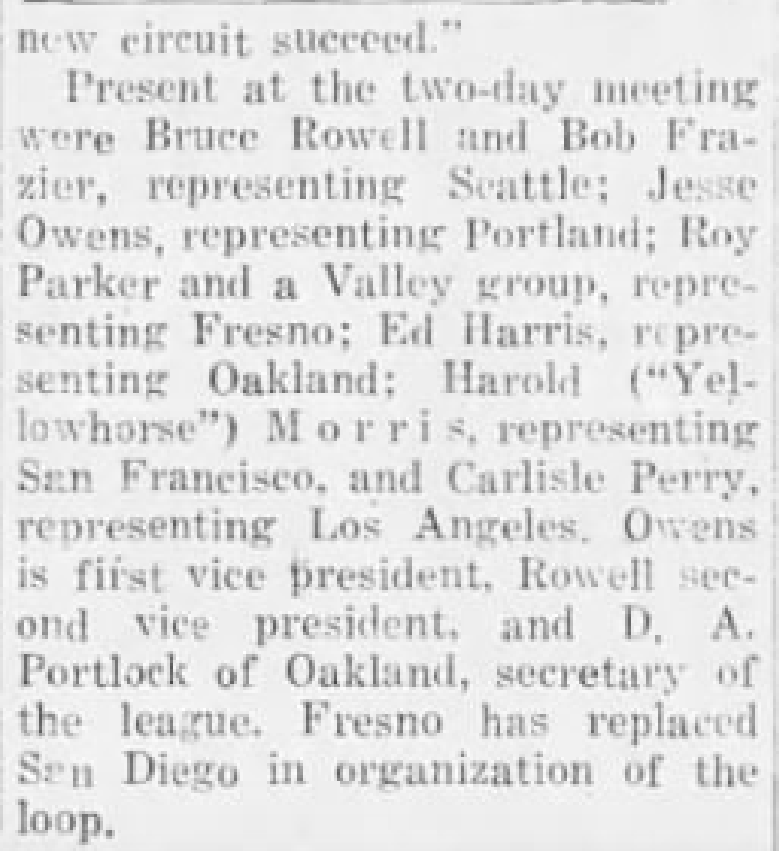

What is notable about Saperstein’s involvement with the West Coast ‘Baseball’ Association, is he was reluctant to take the job as League President. Owens was elected as First Vice President of the League. And a gentleman named Bruce Rowell, who was the manager of the Ubangi Club in Seattle was elected Second Vice President of the league. Former President Pro Tem, D.A. Portlock, was elected as Treasurer of the league. This removed the power base of origination from the West Coast Association out of the hands of the Bay Area founders where the league was formed, into the hands of Pacific Northwest interlopers. What should have been investment became and act of usurpation. There are those that say that Rowell didn’t even actually own the Seattle Steelheads, and that he was nothing more than a proxy for the behind the scenes ownership of the Steelheads for Saperstein. Leaving the newly established West Coast Association with a three to one in favor of the Pacific Northwest teams, when it came to a governing votes by the Board of Directors for the West Coast Association.

Andrew Spurgeon “Doc” Young , sports editor of the Los Angeles based African American paper called the “Los Angeles Sentinel“, wrote a scathing editorial about the fact that Abe Saperstein was allowed to become the President of the West Coast Association. The header read, “Election Of Saperstein To West Coast Baseball Violates Idea Of Negro Promotion”.

So how far back does this legacy of baseball within the African American communities of West Oakland and South Berkeley reach? The answer can be found with that formal meeting to establish a league and charter, which took place on October 18, 1945, by glancing at the address “1219 8th Street”, West Oakland. California. This was the home of the Athens Elks Lodge 70. The organization that was also responsible for the birth of the Berkeley Colored League during the Great Depression, and the Berkeley International League — which was the Bay Area’s attempt of integrating baseball with all racial groups that lived in the East Bay. The Athens Elks Lodge was the place where, community dace were held, and many great early jazz performers got their start. Wade Whaley and his Black and Tan Jazz Hounds were made famous, playing weekly for dances in the 1920’s at the Athens Elks Lodge 70.

The Athens Elks club was known on both sides of the Bay, and was the home of the Black Local 648 musician union. This meant that any African American musician who showed up to town, to play in the Bay Area checked in with the Elks Club; and as it was also a dance hall upstairs, and a bar and nightclub downstairs. It was a place where large gatherings of the African American community took place, a lot of famous musicians passed through its door and played in their hall. Jam sessions between out of town stars and local bands were a constant happening. From Jimmie Lunceford to Billie Holiday, the Elks Club was the place to meet and greet your long lost cousin or your next husband or wife.

In 1945, the usual suspects could be found planning the arrival of a league with its core foundation members linked in the Bay Area and its people, with their strong history of African American baseball on the West Coast. In a period of time just a little over three months, one-hundred days, processed through a series of meetings of the Oakland High Marine Club, a charter was established for the “West Coast Association” was founded in October of 1945. The word “Baseball” was an addition later added by Abe Saperstein, that also became prominent in his correspondence sent to different team managers. It seems that Abe Saperstein was an absentee baseball league President, who never read the league’s charter, but is all too often credited with the league’s original formation, when that story couldn’t be further from the truth.

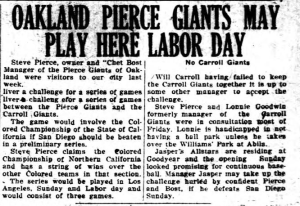

Carlisle Tarleton Perry was one of the first players to play the fields of the Bay as one of the Oakland Giants, playing with team members Chet Bost, Norman O. “Tick” Houston, Hilary Bullet Meaddows, and Jimmy Claxton. He also played for the Pierce Giants of Oakland, and the Shasta Limiteds.

Harold “Yellowhorse” Morris started his baseball career with the Pierce Giants of Oakland. He played ball under the tutelage of team Captain, Chet Bost and Owner Steve Pierce.

The mystery of Steve Pierce has always perplexed baseball historians. He owned a baseball team and he owned a baseball diamond. His popularity in the Bay Area, Central California, and the Napa and Sonoma regions were well known. His players were challenged by teams in Southern California, for the “Colored Champions of California“, and they held their own. Rumor had it that he had once purchased the Detroit Stars. In the summer of 1945, Pierce had returned to Oakland to reinvent the Pierce Giants of Oakland, with two young baseball stars named Mel Reid and Johnny Allen, using “Yellowhorse” Morris as his manager.

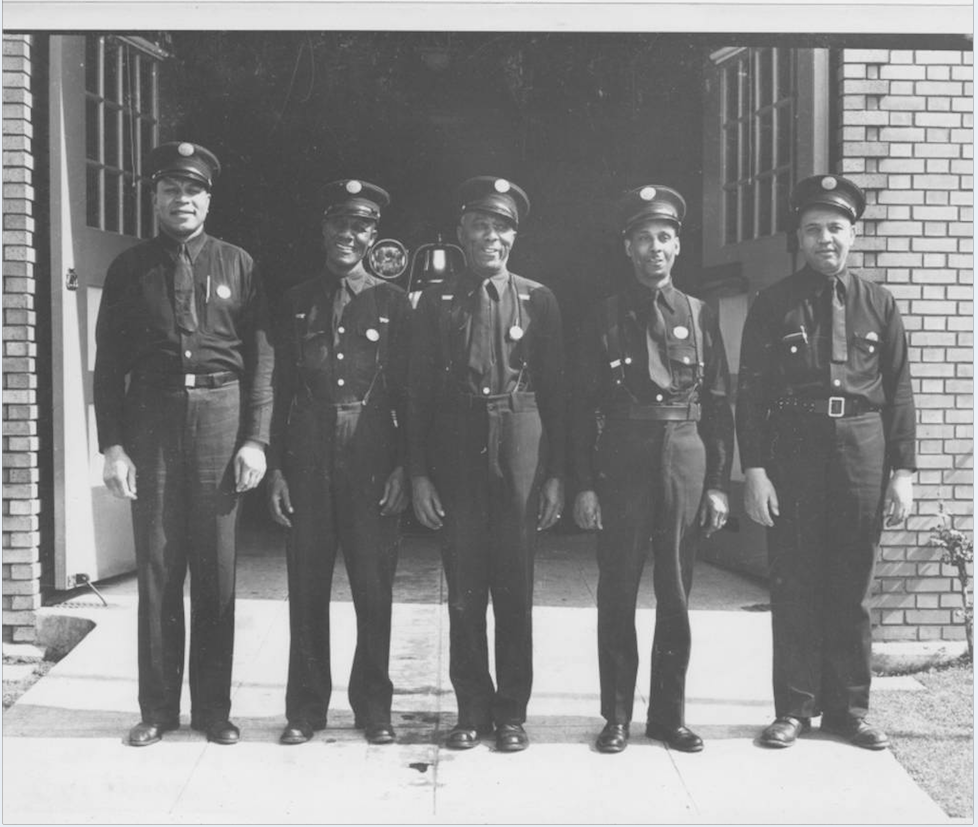

The West Coast Association was the brainchild of Edward C. Harris. In the 1940’s, Ed Harris, a Kansas native, worked for the Works Progress Administration as a Parks and Recreation Director in Berkeley. Verifying his connection as a Fireman in Oakland is seemingly impossible, but if the story is true, he would have been attached to Station 22, Station 33, or Station 28; the only African American fire stations in a city of Oakland, which at that time — had a total of thirty fire engine companies in the 1940’s. Segregation still existed in Berkeley at that time, and a black fireman in Berkeley in the 1940’s was non existent. The Berkeley Unified School District did not desegregate until 1968, although it was the first school system in America to begin the long process of desegregation — moving towards integration in the late 1960’s, by becoming the first school district in the nation to voluntarily implement a two-way busing program.

We do know that Ed Harris played for the California Eagles, which made him well connected to those who played baseball on previous and existing African American teams in the Bay Area. Within that core group of people that Harris played with on the Eagles, Foy Scott, Lionel “Lefty” Wilson, Andrew “Little Sharkey” Auther, and Mel Reid also played for the Oakland Larks as well. Wilson and Auther’s connection to the Larks reaches back to their time spent as team mates on the Berkeley Pelicans of the Berkeley Colored League.

The discussions surrounding the concepts as to why this West Coast Association league failed, as opposed to becoming a successful Negro League like its predecessors, is a very large and often overlooked subject; but one definitely worth studying today, and it shares stunning similarities to what we see happening with the economic impact of COVID-19 on Major League Baseball. Looking at how desegregation and other uncontrollable factors can effect the financial bottom line of even most well established businesses, including the established Negro Leagues, causes a trickle down effect on established communities that once prospered unabated. They lose their financial stronghold within the community that they built from the ground up.

These massive social shifts can carry both an undercurrent and tsunami like effect, when it comes to society as a whole, and a sub-social stratification, like sports that once helped fuel local economies, suddenly disappear and leaves these communities dry after the surge of initial excitement about the coming changes they will bring. Most of the arguments surrounding the West Coast Association’s rise and subsequent fall usually revolve around unfounded comments such as, “they weren’t good enough“, or “they were not financially sound, based on a lack of collecting a franchise fees“.

The creation of these types of comments or falsehoods need to remedied within the larger discussion of baseball. Because they fail to address a very complex situation of supply and demand in the world of sports and entertainment, and how sports survive in a free market environment where you either continue to expand your market place, — or watch your market place collapse and get taken over by the bigger fish in the pond. Major League Baseball understood its own needs for expansion, and for this reason, Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to a financial contract obligating him to be the first of many African American baseball players to join Major League Baseball. This financial concept goes beyond the ‘desegregation into integration’ concept.

It becomes about ticket sales and revenue at the gate. The six original teams represented by the West Coast Association were Seattle Steelheads, Portland Rosebuds, Oakland Larks, San Francisco Sea Lions, Fresno Tigers, and Los Angeles White Sox. Theses teams were the economic gate keepers of the West Coast Association. Their survival depended on an African American working class market place, who could maintain employment on the West Coast after World War II. The ever shifting racial politics in the West, and the decrease in African American employment within the West Coast Military Industrial Complex at the end of World War II also decreased the chances of a new Negro League’s survival. The exponential growth of African Americans to the West Coast during World War II would have easily supported a new Negro League had there been access to larger venues.

Fully understanding how macroeconomics works in a competitive market place should be part of this discussion, because it was was the main reason the West Coast Association failed to make inroads into creating a new Negro League. Three very large forces, coming in from all sides, were working against the creation of the West Coast Association; Major League Baseball, Negro League Baseball and the Pacific Coast League. In 1946, the Pacific Coast League was on a course of reinvention. Expansion was on the plate for Clarence “Pants” Rowland, because he was tired of the Pacific Coast League playing both stepchild and farm league to Major League Baseball.

The assumption of success by the West Coast Association was based on expansion of the Negro Leagues to the West Coast, that would create a West Coast venue for African American baseball players, along with a farm system for the Negro Leagues, similar to Major League Baseball using the Pacific Coast League as a place to tap new talent. The West Coast Association as a new Negro League was a sound idea and worthy of exploration. After seeing the financial drawing power of current Negro League baseball, Major League Baseball plotted a course to play the long game — for the future. It would use both the Negro Leagues and the Pacific Coast Leagues as farms, thereby capitalizing on the best baseball talent available.

With that in mind, and the signing of Jackie Robinson as a precursor to desegregating Major League baseball, it should have been apparent to one an all, including the existing Negro Leagues, that no matter how good the Negro League players were, — or how financially sound the opposing Negro League teams they played for were, — that even those existing Negro League teams as well could not compete in a free market economy where Major League Baseball dominated the social and financial spotlight, and had the financial ability to siphon off the best African American talent of the Negro Leagues and the Pacific Coast League. Salaries of former Negro League players that chose to go to the Major Leagues could not be matched. By remaining in the Negro Leagues, players would be financially handicapping themselves.

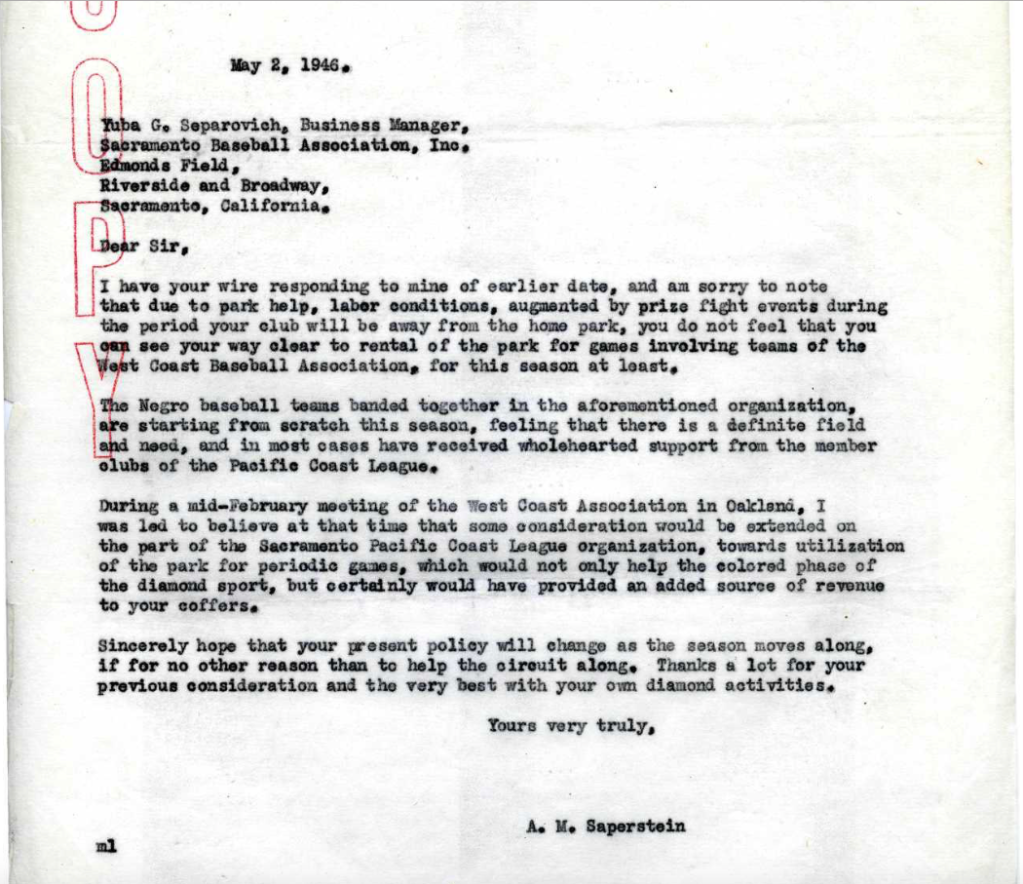

The concept of “Negro players”, playing in large stadiums provided by Pacific Coast League owners, on off days or when Pacific Coast League teams were scheduled to play out of town was totally unacceptable to Clarence “Pants” Rowland, — unless of course it was a ‘once in a blue moon‘ charity event. A new Negro League offered monetary competition to the Pacific Coast League that Rowland would not allow to come to fruition. Accepting the fact that the West differed from the East when it came to allowing African Americans on baseball fields reserved for white-only players was a big part of why scheduling games was problematic for the West Coast Association. Saperstein was pretty naive and non·plussed as a West Coast Association President and league negotiator when it came securing Pacific Coast League parks for the West Coast Association league to play on. Abe functioned from a barnstorming mentality, where games were played all over the United States for amusement. and not for sport. He was more attuned to participating in sales role, but when it came to league management, he lacked hands on operational skills.

Being President of an actual league was beyond his grasp.

And although Saperstein presented a steady resolve in the public’s eye when it came promoting the West Coast Association in the media, the behind the scene action was chaotic and contradictory. Saperstein was not accustomed to the deeply embedded West Coast racism when it came to securing ball parks to play in, leaving the negotiations of securing parks up to team Managers — who were seldom given the time of day by the ‘white-only’ park owners. From the time of his election as President of the West Coast Association, to opening day of the league, Saperstein spent very little time securing the Pacific Coast League stadiums, that he made a pledge to the league that he would secure.

The excuses that were used to prevent West Coast Association games from being played on Pacific Coast League fields were readily accepted by Saperstein, without putting up a fight, and without the tenacity of leadership required to make headway. Abe chose to communicate with his managers Harris, Perry, Morris — and the rest of the West Coast Association — only by letter or Western Union. He treated his responsbilities very nonchalantly, possibly because he had many other money making ventures that took priority over West Coast Association. One could even speculate by the overall amount of correspondence archived and collected on the West Coast Association, that Saperstein never met consistently with the any of the team owners or managers of the West Coast Association, or any Pacific Coast League stadium owners, and conducted most of the league business only by telegram, mail, and sometimes by phone.

The success of African American baseball, which was deeply rooted in the African American culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, would shortly become a thing of the past; causing the rapid decline of West Oakland’s 7th Street’s revenue, and killing off most of the black owned and operated businesses that relied on African American baseball as an economic engine that fueled the black community’s economic survival. The Jazz spots, the Night Clubs, the BBQ joints, the social clubs and meeting houses, — which fostered additional economic engines that trickled down money to every mom and pop business in the black community, were also affected by the demise of the Negro Leagues; both the established Negro Leagues and the one in its infancy.

The barnstorming concept was decimated by the Negro League to Major League crossover of African American athletes, who could not be blamed for wanting to make better money than they ever dreamed of making in the Negro Leagues. The businesses that catered to the African American crowds, — that brought the Negro Leagues to towns all over America, could no longer sustain themselves, when these black owned business — who once flourished and thrived, found their loyal clientele in other neighborhoods, spending their dollars in distant places, far away from their own communities. The radio itself, and television as well, made it possible to see or hear the game at a distance. And the idea of attending a game in person became secondary, furthering the economic decline of the African American community.

There are those that say, “poor planning” caused the demise of the West Coast Association, never taking into account that no Negro League survived desegregation of Major League baseball in 1947. By 1948, the Negro National League disbanded, and by 1950, the Negro American League was a former shell of itself. No business plan could have saved any Negro Leagues. Even though the West Coast Association made an attempt to secure a future place for the African American professional baseball players, there were too many dominating economic factors that crushed every Negro League player, manager, owner, and league Presidents — thereby crushing the Negro League spectators as well.

It took only 49 days from start to finish, to witness the final creation of the very last Negro League charter to be written in America, to the signing of the contract of Jackie Robinson to the Montreal Royals. After that, it took less than four years for the economic demise of every Negro Leagues left in existence, which left the African American communities they financially supported and who supported them as well, — financially decimated by their extinction.

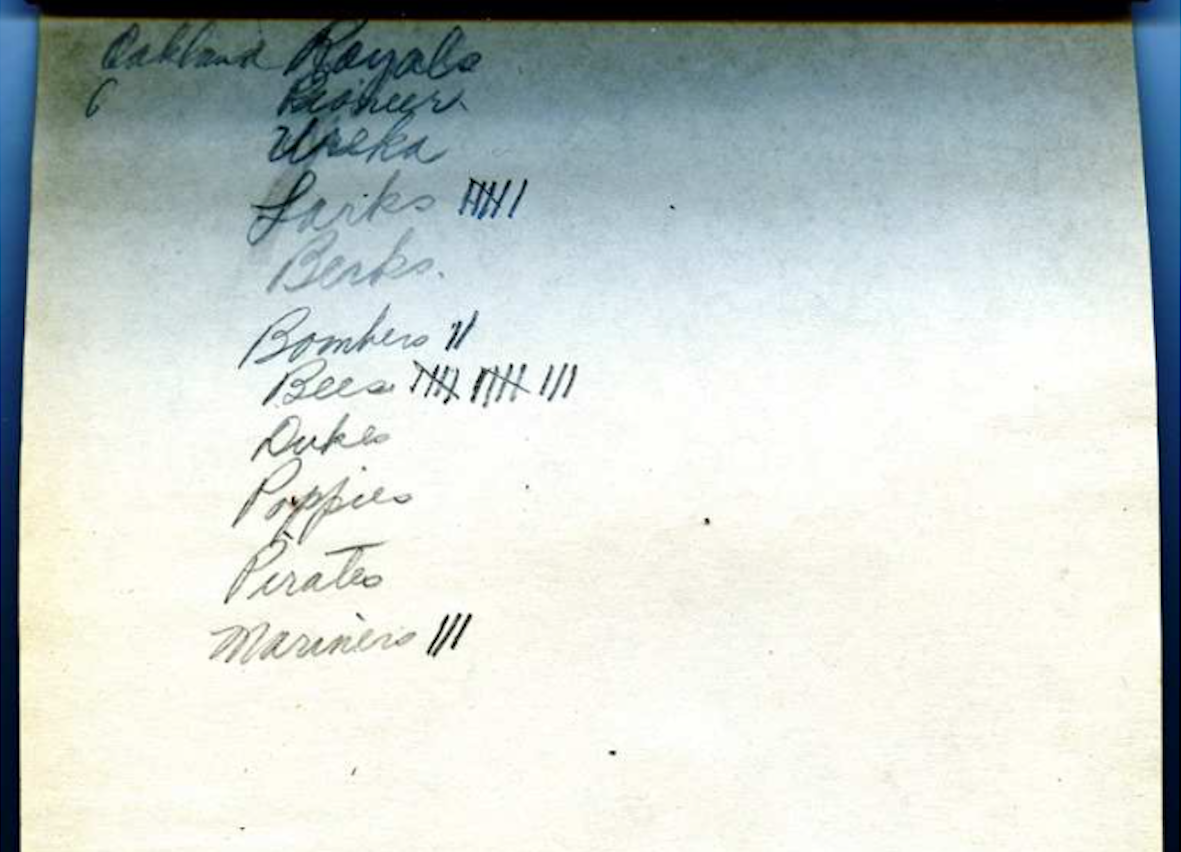

Begging the question: would things have played out differently,…if the Oakland Larks had taken their original name voted on by the members of the Oakland High Marine Club?

Only the alt-universe where the Oakland Bees played baseball would know.