In 1898, the Fort Douglas Brows season would face a turn of events that would challenge any baseball team worth their salt. The men themselves were ready to play. With the field being rehabilitated and grass now on the diamond, the grand stand was also refurbished and repaired by the men who endeared themselves to the recreational time of playing baseball, whenever it was allowed by their commanders. With these crucial things taken care of, the 1898 Browns were ready to play ball this season against any team that came their way. Practices along with military drills were a constant source of their daily undertakings. They enjoyed their new home in Utah. Once the brisk winter months had broken into spring, and the weather became clear and warm, it would be time for the Browns to take up the bat and ball.

In early February of 1898, Private Augustus J. Reid, of Company D, who began his stint with the Browns as their second baseman, accepted his discharge from the 24th Infantry Regiment, re-enlisted, and put in for a transfer to the 25th Infantry Regiment, where he would be stationed at Fort Missoula, Montana. [15]

By mid February, the sinking of U.S.S. Maine took place in Havana harbor, sealing the fate of the final decision on whether the United States should proceed forward and fully engage in a war against the far reaching Spanish Empire and all its interest. Cuba, one of Spain’s colonies, along with the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico were the ‘interest’ that would be scheduled for such a conflict. It would be a short, quick war, that lasted only three months, three weeks, and two days, but the devastation it produced lingered for many years after it was initiated. President McKinley tried his best to avoid war at all cost, but the Democratic Party and Populist Party held sway over the people of the nation, and public opinion polls preferred U.S. expansionism over Spanish Imperialism. The sinking of the Maine made ‘avoidance’ of all out total war with Spain a moot point.

There was still talk of baseball among the citizens of Salt Lake, and it was on the minds of one and all, except for the Fort Douglas Browns after the sinking of the Maine. There were never reasons for the Browns to suspect that there would be a ’98 baseball season, because a soldiers job was to be a soldier first and foremost. That’s what they were trained for, and the men of the 24th infantry Regiment had spent many years going wherever their duty called them. Still, certain business men of the Salt Lake area looked forward to adding the Browns to a newly proposed state league, seeing future dollars roll in from this highly endorsed venture, and the Browns would be a big money draw, as they were now a part of the Salt Lake community.

Activities at Fort Douglas began to reflect less recreational activity and an increase in military training than had ever been seen before. The seat of war would be in Cuba and the rumblings of the U.S. Congress were made clear to one and all, that a special ‘type of soldier’ would be required to fight and win such a conflict. One that Congress felt was immune to tropical diseases, like ‘Yellow Jack’. Yellow Fever was a greater adversary than the actual enemy a soldier would face in combat. Yet, it was determined by a general consensus of political powers in Washington D.C., that men of a certain heritage who derived from a certain areas of the United States, possessed a better chance of survival against this deadly disease. No proof was ever offered that said immunity based on one’s race could prevent the contraction of this disease, but this theory was strongly believed to be the case in the choosing of regiments of Army ‘Regulars’ scheduled to leave for Cuba.

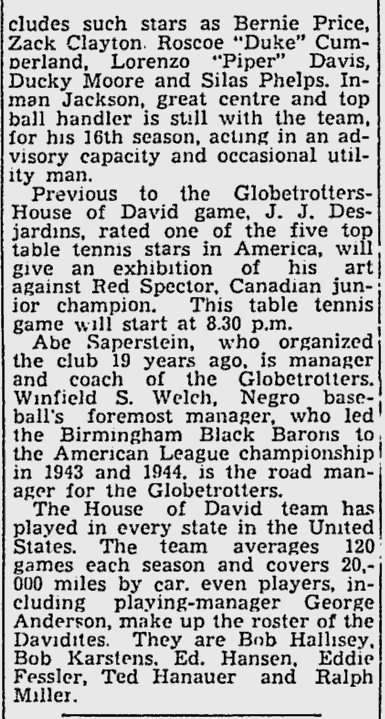

“State League Now in Process of Organization.

That Salt Lake will see an unusually good season of baseball this year, seems evident from the great interest which is already manifested in the national game. A baseball league, which will include teams from Fort Douglas, Tintic, Ogden, and Salt Lake is already in process of organization. This league will play a regular schedule of Saturday and Sunday games throughout the season, from May to October, and at the close of the season, a pennant will be awarded to the leaders in the race.

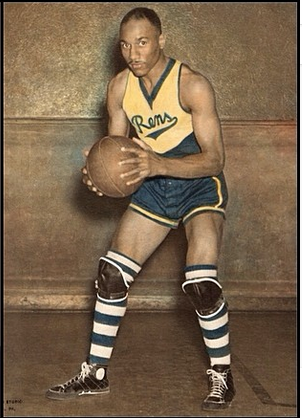

FORT DOUGLAS WEAKENED

The Fort Douglas will lose several of its best players. Reid has accepted his discharge from the Twenty-fourth infantry and has re-enlisted in the Twenty-fifth infantry, stationed at Fort Missoula, Montana. Jackson has likewise received his discharge, but is still in the city, and may be depended upon to play ball with some team during the season. Armstrong will also be missed from the ranks of the Browns. But Capt. Loving has secured some good new material to fill the vacancies. Two new pitchers, Harris and Ray, will be available, and both are experienced men.” — Salt Lake Tribune, March 6, 1898

“Claim that Colored Soldiers Could Do Better Service than White Men.

It is acknowledged by men of experience in southern climates that white men from cool regions of northern states would fare badly in the treacherous climate of Cuba. colored troops are pointed out as the best soldiers to stand the strain, and it is freely prophesied that the four colored regiments of the regular army would be given ample opportunity to win glory if the war breaks out. Those regiments are the Ninth and Tenth cavalry and the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth infantry. — Deseret Evening News, March 15, 1898

As mid March approached, it would be certain that the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment would once again be given new marching orders to go to war. With only a single month’s preparation time, the Fort Douglas Browns would prepared for battle in a foreign land, while at the same time, practiced for one final game in the city of Salt Lake.

Col. J.F. Kent was their commander, would be given the rank of Brigadier General once he reached Cuba, and total control of the 1st Division in V Corps, in which the 24th Infantry Regiment would be attached. Kent would take command of the Sixteenth, Sixth, Second, Tenth, Twenty-first, Ninth, Thirteenth, and Twenty-fourth U.S. Infantry Regiments, along with the Seventy-first New York Volunteers.

“The long expected orders for the Twenty-fourth infantry to march have at last been received. Yesterday evening about 7:45 a telegram was received by Colonel Kent at Fort Douglas notifying him that the regiment would be ordered out either Sunday night or Monday morning. The point to which the regiment will go is not officially known, as the dispatch did not state, but it is understood they will go to New Orleans. There was some little excitement at the post over the orders, but as all the preparations are made, there was little going on at the post. The dispatch which came yesterday evening stated that later order would be sent.

THE CAMPAIGN

In speaking in plans of campaign one of the officers of the Twenty-forth stated yesterday that it was a shame that the army reorganization bill did not pass, and when the army is sent into action the United States will see the mistake. It will be almost impossible to mobilize an army of over 12,000 men from the regular army force, and if the regular army is alone to invade Cuba they will have their hands full. According to the statements of this officer the campaign in Cuba will be a disastrous affair unless it is terminated quickly. In a short time from now the climatic conditions of the island will be such as will cause most of the men to die from fever, and the only hope for them is to fight at once and get out of the country as soon as possible.” — Salt Lake Herald, April 16, 1898

In their final game, before departing Salt Lake, the Browns took on a newly formed minor team called the Salt Lake Colts. Defeating them by a score of 16 to 14, it would be the last game the Fort Douglas Browns would play for a while. [16]

Two days later, the Salt Lake crowds would line the streets in anticipation of watching their brave fighting men, the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment, depart their fair city and in hopes that they would fight victoriously in Cuba and return home safely. There were no detractors among them, as large crowds gathered from near and far at this public event. Heartfelt and saddened by the leaving of the men they had once opposed living in their city, the people of Salt Lake were noticeably disturbed and fraught with fear for the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment. Thousands turned out in Salt Lake City to see them off.

“Twenty-fourth Leaves City Amid Great Enthusiasm.

STREETS LINED WITH PEOPLE

Flowers and Cheers and Flags and Tears

They dressed me up in scarlet red, and treated me so kindly; but still I thought my heart would break, for the girl I left behind me. — Old Song

Amid cheers from thousand of throats, with flags waving, bands playing and hundreds of children sending their fresh young voices out upon the breeze, the Twenty-fourth infantry marched to the depot yesterday and took the train for New Orleans.

It was a stirring scene, the march from the post to the station, and every foot of the road from the reservation to the Rio Grande was occupied by spectators. There wasn’t any school yesterday forenoon. That is, no school to speak of. A few teachers made an attempt to teach the youthful idea how to shoot, but the youthful idea was more interested in the sable faced shooters, who may be sighting rifles this day week.” — Salt Lake Herald, April 21, 1898

As the next few months past, very little was discussed about the men who had departed Fort Douglas headed to war; leaving by train first, and then by boat, eventually landing on the shores of Cuba. The most talked about subject across the nation was the recruitment of the 10,000 “Immunes”, and how their presence would affect the outcome of this war against Spain. The men of the 24th Infantry, by birth right, were considered part of the immune regiment strategy that the U.S. Army had developed and so dearly fought to prove that they could use to defeat of the Spanish Empire. The price of victory had laid a very heavy proposition at the feet of the 24th Infantry Regiment. African American soldiers had always been treated as suspects of cowardice in the face of battle. Cuba would be their testing ground as a fighting regiment; fighting and dying together for a cause greater than themselves.

On July 1, 1898, the battle of San Juan Heights also known as San Juan Hill began. History records a much different story involving Lt. Col. Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders capturing the Spanish blockhouse at Loma de San Juan, but the battle to take the hill was executed by the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment. They fought this battle from the very beginning, pushing forward and never retreating, till San Juan Heights was secured, and suffering the highest casualty rate of any unit that fought the Spanish American War in Cuba. From this perspective, the battle of San Juan Hill was just the beginning of the deaths that the 24th Infantry Regiment would incur at the hands of the enemy.

The first reports of casualties that reached Salt Lake after a three day battle on the heights came from Senator Cannon from Washington D.C. He stated that no officers had been killed during the engagement at Santiago de Cuba, and no enlisted men of the 24th Infantry Regiment had been killed. The only reports out at the battle were that Lt. Col. Liscum, Capts. Brett, Ducat and Dodge had been wounded in the fierce battle to take the blockhouse. The severity of their wounds was still unknown at this point. This first reports would be false, but it was spread throughout the Salt Lake area by newspapers and word of mouth. The deaths and number of wounded men that occurred, were highly understated. [17]

During the recapitulation of the killed and wounded, published on July 8, 1898, General Shafter’s report told a story of complete carnage, brought on by the death hail of hot lead shot from the deadly accurate and legendary 1893 Spanish Mauser. The Spanish M93 outclassed any rifle in the American arsenal used in the war. It used smokeless powder cartridges, and had a longer range than the rifles issued to the American troops. It also used stripper clips for quick reloading, and its bullets flew on a flatter trajectory. American troops using their shorter ranged rifles would need to get within range of the blockhouse to take that hill. The M93’s use of the smokeless powder cartridges made it almost impossible to see where the enemy was firing from, so many of the troops were caught in deadly crossfires. The 1st Division in V Corps troops, commanded by Gen. Kent took the brunt of the battle and chalked up the most casualties at San Juan Hill. In his division alone, twelve officers and eighty-seven men were killed; thirty-six officers and five hundred and sixty-two men were wounded; and sixty-two men were missing in action. [18]

Of those men, under the command of Gen. Kent, the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment led by Lt. Col. E.H. Liscum, two officer and eleven men were killed, six officers and sixty-eight men were wounded, and six men were missing in action. [19]

“We have previously given the testimony of a participant who says the 13th Infantry was the regiment that finally crowned the hill of San Juan and in order to perfectly fair we will add the testimony of another, who says it was the 24th Infantry! These personal notes are valuable and their discrepancies don not lessen their sincerity and interest. “The 24th Colored infantry,” he says, “led the charge, followed by the 13th, 16th, and part of the 71st. Who gave the order for to charge, never will get the credit for it, for he found his grave. Many will claim it, but the officer who cried “Follow me!” and the line he led were wiped out of existence. No General ever ordered it.” This was written by Dr. Winant of Syracuse, who was with the 71st N.Y. Vol. The “part” of that regiment referred to he gives as eleven men, who “broke away and we went up the hill under one of the most murderous fires imaginable, along with the Regulars. This tallies with Gen. Kent’s report. One writer says that about two hundred men of various commands reached the top of the hill in the first successful rush and that their names were taken down. We hope the list will be published and settle this interesting controversy.” [20]

“Don’t you hear ’em, Colonel ? Don’t you hear our boys singing ‘Hallelujah, Happy Land’?”

The colonel had other thoughts, and he answered wearily: ” Hear what, my man ?”

“Why, don’t you hear our boys singing on the hill? Colonel, you give ’em the right steer, suah, and now they’s up there and singing to let you know it, suah, suah. I take my oath,Colonel. They ain’t no regiment in the army that can sing like that but the old Twenty-fourth.”

And both the darkies chuckled, and laughed to scorn any suggestion that they might be mistaken, and that perhaps, after all, the Twenty-fourth men were not upon the hill.

“They’s up there,Colonel,suah. Fac’, I can most see ’em now. You gave them the right steer, suah, and they wouldn’t have gone up if you hadn’t told ’em to.” [21]

“There has been much discussion as to which regiment first scaled the heights. It is pleasant to have to record that the men who have participated in it are the least decided in their statements, and are, it has seemed to me, always ready and willing to give the greater credit to regiments other than their own. It can not be disputed that General Hawkins directed the charge and inspired the men to what followed by his own great courage. There is no question among those who know, that young Ord led the charge that his general directed and that he was the first man on the height at San Juan. There is a great deal of uncertainty as to what happened afterward. My impression is, more from what I heard the evening of the fight than from what I saw, that the flag of the Sixteenth Infantry was the first of our flags to wave over San Juan Hill; that the men of the Thirteenth Infantry captured and hauled down the Spanish colors from the blockhouse; and that there we more men from the Twenty-fourth Infantry, the brave blacks, first on the ridge than any other regiment. But to my mind this is not the place not is there any basis for invidious comparison” [22]

That list of names was never published.

Only the names of the dead and wounded that ascended the San Juan Heights would be recorded for posterity. Validation of the 24th Infantry Regiment’s engagements and actual participation in the Battle of San Juan Hill would become erased from contemporary history, even though many events that taken place had been well documented. To their credit though, one major event that took place after the Battle of San Juan Hill that showed the 24th’s commitment as soldiers first, was their dedication to the sick, wounded, and dying troops who occupied the field hospital at Siboney. For two weeks, up till July 14, 1898, the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment had occupied wet trenches as part of the garrison protecting Loma de Santiago, before they were ordered to march to Siboney’s yellow fever field hospital traveling along the El Camino Real. It was a request by the hospital’s field commander for the 24th Infantry Regiment to perform guard duty in mid July as added protection. [23]

There were very few cases of the outbreak at the time of their arrival in mid July. No more than 14 men had contracted ‘Yellow Jack’. The number of cases would grow exponentially within less than a month’s time. This unseen enemy on Cuban soil would soon become nightmarish, and also responsible for the the bulk of casualties to American troops that took place once they reached this foreign land, or on their return from duty once back at home in the United States. The long lasting insidious results of yellow fever were carried home by many of the men who participated in the Spanish-American war.

On July 13, 1898, the town of Juraguacito was was set ablaze and laid to ashes by the troops stationed there, on the orders of Major Legaro of the Hospital Corps and the Army Health Authorities. He felt that that buildings, which were old and falling apart, were the cause of the yellow fever outbreak. Having no idea how yellow fever was spread, this act was done as a safety precaution in lieu of of any other options, because suspicious cases of yellow fever began showing up in healthy soldiers who had not contracted the disease up until mid July. Soldier had been warned not to drink the water unless it was boiled first and not to eat the fruits of Cuba unless they were was completely ripe. Fifty buildings were set on fire to remove all germs or any remnants of disease which could be transferred to the wounded soldiers who occupied the city of Juraguacito. [24]

“When through the deep waters I call thee to go,

The rivers of woe shall not thee overflow;

For I will be with thee, thy troubles to bless,

And sanctify to thee thy deepest distress.

When through fiery trials thy pathways shall lie,

My grace, all sufficient, shall be thy supply;

The flame shall not hurt thee; I only design.

Thy dross to consume, and thy gold to refine.”

Leaving their trenches at Loma de San Juan at 5:30 PM, 15 officers and the remaining 465 men of the 24th Infantry Regiment could be heard singing as they marched toward Siboney. The march would be a nine mile trek beginning late in the day and stretching into the night, taking five hours through jungle trails with dense vegetation, thickets and streams, and sometimes over moonlit barren land. As they descended into the area of their new assignment, their deep, rich voices echoed in the valley along the King’s Road, and the song “How Firm A Foundation” could be heard in the far off distance; resonating as far off as Pablado Sevilla, as the remaining men of the 24th Infantry Regiment approached the newly ‘tented’, yellow fever hospital. [25][26]

“The Twenty-fourth Infantry was ordered down to Siboney simply to do guard duty. When the regiment reached the yellow fever hospital it was found to be in deplorable condition. Men were dying there every hour for the lack of proper nursing. Major Markley, who had commanded the regiment since July 1st, when Col. Liscum was wounded, drew his regiment up in a line, and Dr. La Garde, in charge of the hospital, explained the needs of the suffering, at the same time clearly setting forth the danger to men who were not immune, of nursing and attending yellow fever patients. Major Markley then said that any man who wished to volunteer to nurse in the yellow fever hospital could step forward. The whole regiment stepped forward. Sixty men were selected from the volunteers to nurse, and within forty-eight hours forty-two of these brave fellows were down seriously ill with yellow or pernicious malarial fever. Again the regiment was drawn up in a line, and again Major Markley said that nurses were needed, and that any man that wished to do so could volunteer. After the object lesson which the men had received in the last few days of the danger from contagion to which they would be exposed, it was now unnecessary for Dr. La Garde to again warn the brave blacks of the terrible contagion. When the request for volunteers to replace those who had already fallen in performance of their dangerous and perfectly optional duty was made again, the regiment stepped forward as one man.

…

Of the officers and men who remained on duty during the forty days spent in Siboney, only twenty-four escaped without serious illness, and of this handful not a few succumbed to fevers on the voyage home and after their arrival at Montauk.

…

Some forty men have been discharged from the regiment, owing to disabilities resulting from sickness which began in the yellow fever hospital.” [27]

Eight other white regiments, when asked by their commanders, had refused the nursing assignment the 24th Infantry Regiment undertook. By July 30, 1897, there were 4,278 sick at Siboney; total fever cases 3,406; 696 new fever cases reported on that day. The fast spreading epidemic had proven that black soldiers were no more immune to yellow fever than white soldiers. The leaking of the “Round Robin” letter by a war correspondent of the Associated Press, that was written by Lt. Col. Roosevelt to General Shafter on the issue of bringing the Army home added to concluding the war in Cuba, reached the American newspapers by August 4, 1897. The publication of this letter enraged and embarrassed President McKinley and his Administration. They considered court martial for every officer that signed it, as it was a breech of Army regulations and military discipline. It had placed the entire yellow fever situation out in the open and in plain view of the American public. They demanded that all the troops should come home immediately, even though Roosevelt had stated in the ‘Round Robin’ letter, that the four regiments of ‘Immune’ ‘Regulars’ should remain garrisoned in Cuba.

On August 26, 1898, after forty days of faithful nursing service under the most impossible conditions, the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment marched out of Siboney, debilitated and weakened at their core, caused by the infectious ‘Yellow Jack’ which had depleted them not only as soldiers, but as men. What was left of their regimental band played and they proudly flew their colors as the marched out of Siboney. Boarding the transport steamer Nueces for Camp Wikoff, Montauk, N.Y., of the 15 officers and 456 men that marched into Siboney, only 9 officers and 198 were able to march out. The ravages of yellow fever, typhoid, and pernicious malarial fever had taken its toll on the men of the 24th. They remained at Montauk for a minimum of three weeks in recovery before some of them were allowed to return to Fort Douglas, Utah.

Men like Pvt. James Richards, who was the star pitcher for the ’97 Fort Douglas Browns, met his fate at Siboney, dying on Aug. 21, 1898 of yellow fever. He won a certificate of merit for his time spent on the battlefield, in the signal corps, during the battle of Santiago. In 1890, he had served as a sergeant at Fort Huachuca before making a request to be transferred to the Presidio in San Francisco, to take a Signal Corps course in telegraphy and his transfer was denied. He was demoted to a private for making such a request. He received orders to report to regimental headquarters at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, where he was told he’d have plenty of opportunity to practice. [28][29]

Many of the other wounded men of the 24th, who were not infected by Yellow Jack, traveled back to Camp Wikoff on the hospital ship Olivette and then returned to Fort Douglas by train; such as Frank Hellems, who returned to Fort Douglas earlier to recover from his strange gun shot wound.

“Musician Frank Hellems of Company C, Twenty-fourth infantry, was a noncombatant, but he wanted to see what was going on. So crawled up to the fighting line and laid down flat on his face. There came along a bullet which entered just above his left shoulder and made a neat hole obliquely through the flesh of his back and came out just over his left hip. Musician Hellems jumped and yelled.”

Surgeons Say Captain Knox’s Curious Case Peculiar Wounds of Musician Frank Hellems.

Among the 274 wounded men whom the Olivette brought back to New York from the battlefields of Cuba are some of the most extraordinary cases of injury known in surgical history. When the war is over, it is probable that military and naval methods of warfare will not be the only things to have been revolutionized. There are indications that most, of the surgical axioms which relate to gunshot injuries will have to be revised. 5 of the men on the Olivette are almost shot to pieces. There are men who can show as many as eight bullet holes, and by all the traditions of surgery they ought to be dead. Instead they are alive and not over particularly uncomfortable. Men who were shot through the kidneys, liver or lungs are able to walk around.” [30]

“Corps. Thomas W. Countee, David Holden, who was seriously wounded in the battle of San Juan, and James M. Dickerson, Company F, Twenty-fourth infantry, have been promoted to sergeants.” — Salt Lake Tribune, August 26, 1897

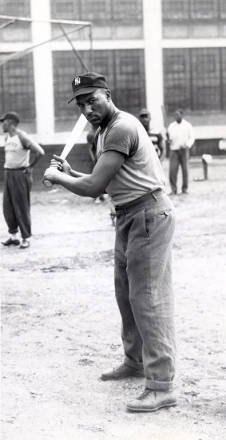

The small number of troops which had remained stationed at Fort Douglas during the war tried to put together a baseball team, paving the way for the arrival of the rest of the regiment that would come home from Cuba, in hopes that they could return to playing ball once again. The way they once played, in front of the cheering crowds of thousands of Salt Lake fans who were filled with adoration for the men of Fort Douglas. Playing like the Browns of ’97. Playing against the best teams in the region, both near and far, as an effective, nearly unstoppable team. Yet, there were very few good men to chose from, to make a good team of those who had remained at the Fort Douglas post. Most of them were not trained in the sport by those who went off to war. Ten days after Frank Hellems arrived back at Fort Douglas on August 18th, he was one of the men that tried his best to play the sport again. Hellums was one of the early Fort Douglas Browns, who played at the beginning of the 1897 season.

“Colored Player Go Down Before Short Line.

THE SCORE WAS 22 TO 6

RETURNED SOLDIERS PLAY

Hellums who returned from Santiago some ten days ago, played first for the Browns and put up a fair game for a man who has been dallying with a game where the balls shriek and whistle and the man who stops one them doesn’t care to play any longer. A fairly good crowd saw the contest.” — Salt Lake Tribune, August 29, 1898

“Harris was clearly out of condition and before the game was half over he became dispirited at the ragged support he was getting from the field and, as he said afterwards, “gave up trying”. The Short Lines played to win from the first inning. When the game was ended there were a good many disgusted soldiers at the fort who had hoped that the Browns would finish up better with their opponents. But the players themselves seemed to be in no wise discouraged.

“It was only a practice game,” said Catcher Jackson

“I haven’t played ball all summer,” said Harris, who has been spending the hot months pitching bullets at the Spaniards from the muzzle of a rifle. “We’ll get another chance at them and do better next time.” — Salt Lake Herald, August 29, 1898

In early September, it was reported that the 24th would soon be coming home to Utah. Still, the Browns as a team, were not close to what they had been. They scheduled games, but most of them never came to fruition. The reason being, the talent just wasn’t there at the the fort and wouldn’t be returning any time soon.

“PLAYED BASEBALL AT FORT DOUGLAS YESTERDAY

The Game Was a Poor One–Resulting In a Victory For the Short Line By A Score of 15 to 12.

There was a baseball game at the Fort Douglas grounds yesterday afternoon between the Oregon Short Line team and and another aggregation styling itself the Browns, taking on the name of the old Fort Douglas nine that made such an excellent record before the boys had to go to war, in order to draw a crowd. As a matter of fact very few of the original Browns’ team were there, and the new organization lacks a good deal of reaching the standard of the old nine.

Harris started in to pitch for the Browns, but gave up in the sixth inning, and Armstrong was substituted. He did some good work, and considering the fact that the nine was made up of whatever material could be found among the colored population of the city, they gave him support. Had the Short Line boys played their usual game it would have been a one sided affair, decidedly so, but as it happened they didn’t and the score was pretty even.” — Salt Lake Herald, September, 12, 1898

The reporting of the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment who had left Fort Douglas to fight in Cuba and their heroic actions on the battlefield dominated the newspaper in the Utah region.

“WORDS OF JUST PRAISE FOR THE REGIMENT

They Were the First on San Juan Hill–Duty at Fever Hospital–Proud to Return to Salt Lake.

Fort Douglas, Utah, Sept. 14.– Now that all the Fifth army corps has been removed from the malarial-loaded clime of Cuba, and some are now on their road to their proper stations, and others under orders, while others are awaiting orders, yet no one tires of reading and listening to the stories written and told by eyewitnesses of the great human struggle for the cause of humanity just ended between the United States and Spain. When the regular soldiers left their stations last spring, under orders to proceed to some Southern city or port, not one-tenth of the vast number realized what was before them. That war was declared they knew, that the United States would never seek peace they also knew, yet none of them, or very few, ever believed they would have to undergo what they have, and what many succumbed to.

When ordered to the front the regiment advanced as if on skirmish drill on the lower parade ground at the fort. And the charge on Fort San Juan was made with the same fervor as they charged upon that little hill just east of the baseball park. The falling of men on every side of them, and the apparent demoralization of the whole regiment directly in their front, neither served to demoralize or dishearten this regiment. There was nothing to encourage them to go onward, unless it was the prospect of death. Bullets as thick as hail, and falling just as fast around them, and coming, it seemed, from the rear as well as from the front and each flank, was the only encouragement they had to move to the front. Their gallant commander having fallen, yet they were not undismayed, but they kept going to the front and to victory. No thoughts of retreat ever entered the minds of theses men, and not a vestige of fear ever entered their hearts. After the fall of their , gallant commander, Lieut. Col. E.H. Liscum, now a Brigadier-General of volunteers, a feeling of revenge seemed to inspire them to greater activity.

But this noble regiment did not stop with the surrender of Santiago. They were hardly dry from the dampness of the trenches when they were called upon to face the deadly yellow jack, which was many declared, worse than the Mauser bullets. Yet they faced it with the same degree of fearlessness and just as cheerfully. They were called upon, and they felt it their duty. They did do their duty there too, and acquitted themselves as nobly as they did on the charge and in the trenches. All night long on the night of July 15th, they plodded through mud, dew and dense tropical undergrowth to the yellow fever hospital, where they were to suffer everything but death. What the Twenty-fourth infantry has endured during this campaign is known only to them and the Almighty God.” — Salt Lake Tribune, September 16, 1898

Warnings issued to the people of Salt Lake about the impending return of the troops to Fort Douglas and Salt Lake area were also a major part of the daily news cycle. They were written to remind the citizens of what their favored sons, the 24th Infantry Regiment, had been through during their battles while fighting in Cuba. Stressing the high points that some of these men returning to Fort Douglas were not the same men who left Fort Douglas. Close to one-thousand men were assigned to return to Fort Douglas, after the closing of Camp Wikoff, and this decimated regiment would increase in numbers, but it was noted that Fort Douglas could not house that many troopers. Still, there would be many new faces to look upon. Most of those men who had left, would never return to their fair city, and that the citizens of Salt Lake City were warned in advance, that their favored sons were no longer coming home.

“IT WAS MOST WELCOME NEWS AT THE FORT.

How the Heroic Fighters and Nurse will Appear When They Return–Personal Notes of Members.

Correspondence Tribune.] Ft. Douglas, Sept. 19–The welcome news was received at the post Sunday night that the gallant Twenty-fourth infantry was ordered to again take station at Fort Douglas. The news arrived just in time to offset an opinion which was fast gaining prevalence that the regiment would be ordered to some Southern station or that it would probably be sent back to Cuba for the winter.

There has been much speculation and uncertainty as to the disposition of the four colored regiments ever since war was declared, and it was no common thing to hear it said that the Ninth and Tenth cavalry and the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth infantry were left in Cuba for garrison duty and that they, with the immunes, would constitute an army of occupation. A good many went so far as to say that that was the plan of the War department, but it seems that those rumors were set afloat by those who were afraid that they would be left in Cuba, and they wanted to set their fear at rest by believing the four colored regiments were to be left.

When the regiment makes its appearance at the depot here in Salt Lake City the many friends of it will have to look at more than one face before they will recognize one of the faces that marched through the streets of the city so gallantly last spring.

There will be just as many, probably more, but they will be strangers. Of the five hundred and more men that went away there will scarcely be more than 200 hundred of that number in line. Many of them that are absent will never march again; they are sleeping beneath the sod of a foreign clime where they so bravely fell for their country and the cause of humanity.

As they march through the streets on their return, let every one bear in mind, that they are conquering heroes. Many more that will be absent, let it be remembered, are suffering from some dread disease, and from which they will never recover. And of those that will be present, many of them will yet succumb to some poisonous disease, which is slyly but surely sapping up their life’s blood.” — Salt Lake Tribune, September 20, 1898

Camp Wikoff, Montauk Point, N.Y.

“The Twenty-fourth infantry has had its orders changed, owing to the discovery that Fort Douglas, in Utah, is only a half-regiment post, and cannot accommodate the whole regiment. Therefore half the regiment will go, as originally ordered, and the other half will go to Fort Russell, Wyoming.

The hospital now contains 515 men. Many of these are beyond hope, and for two weeks, it is feared, there will be many deaths, mostly from typhoid fever.

The division hospital tents are being taken down and fumigated and then turned in. The hospitals are all now out of existence except the main one. There were two death today in the hospital.” — Salt Lake Herald, September 21, 1898

There would only be two games left to play at the end 1898 season for the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment. The new Fort Douglas Browns would play against the Oregon Short Line team shortly after the arrival of the 24th Infantry Regiment’s return to Fort Douglas from Camp Wikoff. These new Browns would take up the ball and bat against the Salt Lake Elks, a group of players formed from the former Park City Miners of 1897. The 24th Infantry Regiment pulled into the station on September 30th, but did not disembark their Pullman cars that evening. It had been a long trip home from New York, and the men slept in the train cars while the officers slept in their berths. A crowd of two hundred people gathered to see them as they pulled up to the depot, but they would not exit the train and march to Fort Douglas till the morning October 1, 1898. By 10:00 AM the next morning, 2,500 people had gathered, braving the cold weather, to welcome their heroes home from war; and as the crowd grew to 10,000 spectators within the next half hour, orders were given to leave the train and begin the long trip to Fort Douglas, where a banquet awaited the humble return to Salt Lake.[31]

On October 9, 1898, the Browns would lose to the Oregon Short Line nine, by a score of 18 to 2. Harris could no longer pitch, and was moved to third base, and Hellems continued his stay at first base. Their whole team was new and untested. They didn’t play together very well. Most of their star players of 1897 had died either in battle, or were ravaged by the yellow fever they contracted during their stay in Siboney.

“SHORT LINES HAVE EASY PREY IN THE BROWNS.

Score 18 to 2, a Very One-sided Showing–The Browns Lacked Practice, But gave Evidence of Ability.

The baseball game at Fort Douglas grounds yesterday afternoon between the Oregon Short Line team and the Browns turned out to be a very one-sided affair. The soldiers at no stage of the game had any possible chance of winning, and it was an accident that they scored any runs at all. The Short Line team began in the first inning and continued a procession over home plate until they had 18 tallies to their credit. The soldier boys didn’t get any during the first seven innings, but in the eighth and the ninth brought each a man over the square.

The crowd was one of the largest ever in attendance at a game on reservation grounds, the enthusiast evidently expecting to witness a good game. Many, too, were drawn thither from purely patriotic feelings , being anxious to manifest their interest in the returned heroes from San Juan hill. It may have been the charge at Santiago heights has taken much of the sporting stamina out of them; certain it was they did not play a very good game. In justice to the team, however, the fact should be noted that they have no opportunity to practicing together. There are many excellent players in the nine, and with practice, will be formidable opponents for any team in the state.” — Salt Lake Herald, October 10, 1898

Only five hundred spectators showed up for the Browns final game, played on October 23, 1898, between the Browns and the Salt Lake Elks. Sgt. Mack Stanfield, who had previously been the manager of the Fort Douglas ’97 team, acted as the field umpire for the game. Sgt. Stanfield was one of the many men who was wounded at the battle of San Juan heights.

“THEY DEFEATED THE BROWNS AT FORT DOUGLAS

The game was called at 3 o’clock. Sergt. Stanfield and Joe Smith were chosen as umpires. The Elks went to bat first, and before the colored men had gotten thoroughly aroused four men scored. This was due to the poor work of the Browns in outfield, which was marked all through the game. This team, however, needs only practice to make it a strong aggregation . Willis is its second baseman , and a former left fielder in the Chicago Union team, did some excellent work, both at bat an on base. The team, with the exception of First Baseman Hellems and Pitcher Harris is made up of recruits recently brought from Kentucky, but nearly everyone showed experience on the diamond.” — Salt Lake Tribune, October, 24, 1898

Whether or not “Willis” was actually Willis Jones of the Chicago Union is subject to speculation. As an Independent Club, the Chicago Union only played four games in 1898. What is no longer open for speculation is the fact that Armstrong, Jackson, and Willis, three of the Fort Douglas’s most valued players, played on a predominately white team in 1898.

“Jackson has likewise received his discharge, but is still in the city, and may be depended upon to play ball with some team during the season. Armstrong will also be missed from the ranks of the Browns.”

Taking a closer look at the Elks of Salt Lake later in the season, Jackson, Armstrong and Willis had joined the team, playing side by side with former rivals on what could be considered an ‘integrated’ team. Jackson began playing with the Elks around mid September 1898, and Armstrong and Willis followed Jackson shortly after in early October of 1898. Former second baseman Meinecke, from the 1897 Park City Miners, was second baseman for the Elks, and was the standout position he normally played for every team that recruited him. Meinecke also played for the ’97 Salt Lake Cracks, and the ’98 Eurekas — a new Park City team put together by ‘Old Hoss’ Harkness. The Eurekas only played a single game that season. They were defeated by the Elks in early June, by a score of 17 to 8, also losing the side bet of $100. McFarland, who played for the Elks, also played with the ’97 Oregon Short Line nine, ‘and the 97 Jubilees. Even the Oregon Short Line player, Hughley, eventually defected to the Elks of Salt Lake.

“The Elks bested the Ogden team in a closely contested game at the Fort Douglas grounds yesterday. The visitors put up good ball but the home nine, reinforced by Jackson, the colored catcher from the Browns, won out by a scratch. The day was so cold that not many ventured out, save the cranks. There was considerable money changed hands on the result, the Elks taking the long end. George Bennett, bicycle and baseball enthusiast, place coin on the Elks and went home a happier man, while the other fellow dropped off to make a meal out of a hot tomale.

Armstrong pitched a strong steady game for the home team and was hard to find. With Jackson behind the bat the Ogdenites had difficulty in scoring though they put up a pretty good game all through.” — Salt Lake Herald, October, 3, 1898

“In the Eighth Inning, When Score was 16 to 13, the Short Line Club Quit Because of a Decision.

The trouble which ended the eight innings of alleged baseball arose out of a question of jurisdiction between Umpire Smith behind the bat and Umpire Stanfield in the field. Jackson of the Elks had reached first on a Short Line error, and was caught between first and second on what Umpire Smith called a balk by Kidder. Stanfield called Jackson out, but yielded to Smith’s decision. The Short Line refused to play unless Jackson was decided out, and Smith gave the game to the Elks.

It was perhaps fortunate that this game was the last of the season. Another game like it would hardly draw a corporal’s guard to the field. And yet the crowd had lots of fun. It started in to guy the players right at the beginning. Hughley, the Short Line seceder, wore an Elk uniform, and he was the butt of most of the jeering. His every move was watched and commented upon with caustic sarcasm by the crowd. Brig Smith got his share of the comment, and scarcely a man on the two teams escaped unscathed.

Armstrong of the old Browns pitched for five innings for the Elks, and was then replaced by Brig Smith. Neither was particularly effective, and their support was not good save in one or two innings.

Comment on the game is unnecessary. It was a footrace around the bases, with the Elks leading by a neck except for half an inning. Griggs and Barnes made two nice captures of long flies, and Willis, a clever colored lad, recruited to the Elks from the Browns, made a fine stop and throw to first, which brought him an ovation from the crowd.”– Salt Lake Tribune, October 31, 1898

In the month of October, many men of the 24th succumbed to relapses of yellow fever that had followed them home. It was a constant concern of the U.S. military in discovering the cause of this detrimental and debilitating disease which continued to curse the men of the 24th Infantry Regiment.

“COLORED SOLDIERS STILL SUFFERING FROM CAMPAIGN

Many Case of Malarial Fever–Sergeants Appointed to Lieutenancies In the Ninth Immunes.

Notwithstanding the strenuous efforts to crush the dread disease, the Twenty-fourth infantry is to a certain extent still the clutches of malarial fever. In the month of October the post hospital received and treated 250 cases of sickness, about 175 of which were types of malaria, and the remaining number being convalescent cases of yellow fever and tonsolitis. There are at present 83 men on the sick report, 21 of whom are accommodated at the hospital, crowding it to its utmost capacity. the average number of new cases is 15, in most cases the illness is a relapse, the patients having been under treatment for the same cause at Montauk Point. Owing to the healthful climate, the present condition is not considered serious, and it is hoped to check a further spread of the disease.” — Salt Lake Herald, November 4, 1898

End: Part III

Part I Part II Part IV

[15] Salt Lake Tribune, February 6, 1898

[16] Salt Lake Tribune, April 18, 1898

[17] Salt Lake Tribune, July 4, 1898

[18] Ogden Standard, July 8, 1898

[19] Genealogy Quest » Spanish American War » 24th Infantry, 1st, 2nd and 3rd July 1898

[20] Army and Navy Journal, August 20, 1898, pg. 1053

[21] Stephen Bonsol, “The Fight For Santiago”, Doubleday & McClure Co., New York, 1899, pg. 170

[22] Stephen Bonsol, “The Fight For Santiago”, Doubleday & McClure Co., New York, 1899, pgs. 196-197

[23] Stephen Bonsol, “The Fight For Santiago”, Doubleday & McClure Co., New York, 1899, pg. 433

[24] Ogden Standard, July 13, 1898

[25] Stephen Bonsol, “The Fight For Santiago”, Doubleday & McClure Co., New York, 1899, pg. 433

[26] T.G. Steward, “The Colored Regulars in the United States Army”, A.M.E. Book Concern, Philadelphia, 1904, pg. 222

[27] Stephen Bonsol, “The Fight For Santiago”, Doubleday & McClure Co., New York, 1899, pg. 433-434

[28] Salt Lake Herald, August 23, 1898

[29] William A. Dobak, Thomas D. Phillips, “The Black Regulars, 1866-1898″, University of Oklahoma Press, 2001, pg. 52

[30] The Gazette from York, Pennsylvania, August, 28, 1898

[31] Deseret Evening News, October 1, 1898

![Clayton, Zack [standing far right Charles Cooper standing center]_BPA001X2019400000024_Ronal Auther](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/clayton-zack-standing-far-right-charles-cooper-standing-center_bpa001x2019400000024_ronal-auther.jpg?w=440)

![Clayton, Zack [L-R Ted Strong, Zack Clayton, Williard Jesse Brown, Jack Matchett+Bonnie Serrell]_BPA001X20](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/clayton-zack-l-r-ted-strong-zack-clayton-williard-jesse-brown-jack-matchettbonnie-serrell_bpa001x201.jpg?w=440)