![Boilermakers A26 baseball team; [E.F. Joseph collection, Careth Reid; Sports]](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/boilermakers-a-26-team-1942.jpg) A-26 Boilermakers, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

A-26 Boilermakers, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

The story of the men and women that built the Liberty ships and Victory ships is seldom delved into, and it covers a lot of turf of West Coast history. History that requires a rather large area of usable land located near water, where smoke billowing factories were in close proximity to one another, pumping out steel and iron around the clock, leaving the residue of soot and the smell of industry in the air. This is one of history’s “Known unknowns“, based on scattered information and limited access to materials to flesh it out in its entirety, because “loose lips” never built ships. There were many former Negro League players that did not serve in the military during World War II, but not because they were not fit for duty. Some of them were part of the war effort that supplied the machinery for the war, which in some cases — they worked in the war materials industry long before the United States entered World War II.

Their faces are familiar among this group of men.

There are also many different sides to the stories that surround American society during World War II, that one might be compelled to explore the deeper meaning of an simple image, such as a picture — if you will, — and its origin and simplicity. Like this picture of the A-26 Boilermakers; taken twenty-one years before Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech was given during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, calling for civil and economic rights and an end to racism in the United States. The original March on Washington Movement began in 1941, headed by A. Philip Randolph.

“Why Should We March”, March on Washington flier, 1941 – Library of Congress

Some images are are misinterpreted; some of them are yet to be explored; most them will never be revealed. The industrial baseball side of baseball is often left open ended, and many questions are left unanswered. In a rare find, photographs such as this one, share a much larger picture of American society, the role of the military industrial complex, and how African American baseball functioned before and during the war, both before and after America entered the war as a participant of the Free World vs. the Axis Power conflict — that was raging in Europe and the South Pacific, after that fateful day in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

The majority of men pictured here were involved in the ship building industry years before America’s involvement World War II. They worked at different ship building facilities in and around the San Francisco Bay Area. The “Ten Prohibited Subjects” were a way of life for everyone during World War II, so limited information about the A-26 Boilermakers and their movements in and around the San Francisco Bay Area is something that is acceptable and expected, under the circumstances that they lived through.

From Permanente/Kaiser Yard #1, Permanente/Kaiser Yard #2, Permanente/Kaiser Yard #3, Permanente/Kaiser Yard #4, Moore Dry Dock, Mare Island,and Marinship Corporation, they went where their skill sets were needed. Yet, the social dynamics of how the A-36 Boilermakers baseball team came into being reaches as far back as 1936, when the barnstorming St. Louis Blues were touring the Bay Area, and a few of them decidedly remained on the West Coast. Exploring an array of job opportunities that they couldn’t find anywhere else in the United States at that time, based on the limitations of race and social status, some of these men forged a new team. From the break up of the St. Louis Blues, the California Blues evolved, created by Byron Speed Reilly, founder of the Berkeley Colored League, which became the Berkeley International League.

Berkeley Daily Gazette -May, 27, 1937

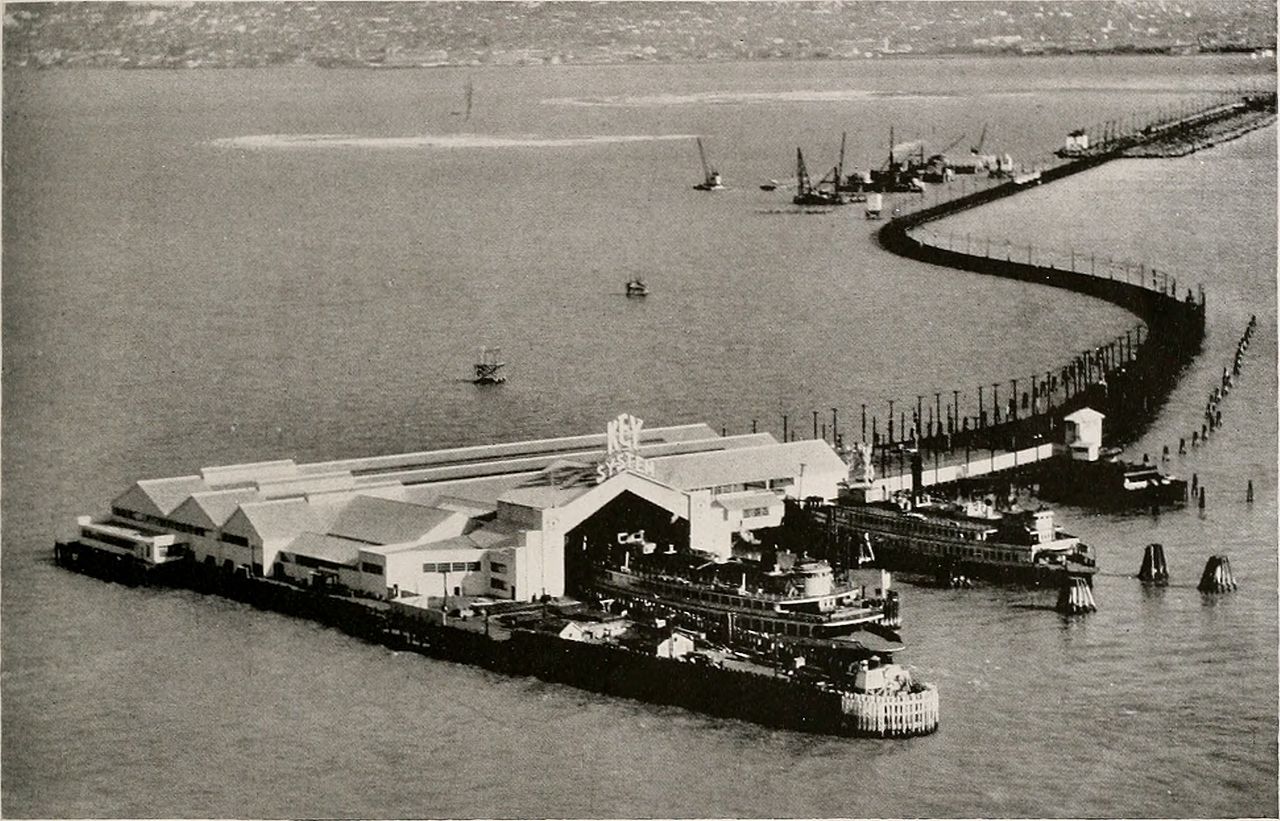

This story begins at Moore Dry Dock, founded in 1905 as Moore and Scott Iron Works in San Francisco. Shortly after the San Francisco Earthquake in 1906, Moore and Scott Iron Works migrated its ship building operation to Oakland, California in 1907, and stationed itself near the inlet channel of the Oakland Estuary. It was strategically placed where the Central Pacific Railroad’s Oakland Long Wharf was once located, with access to railroads, and the Key System cars that connected the entire East Bay by trolley, and access to San Francisco by Key System ferry.

1885 map of Oakland and the CPRR’s Long Wharf

Key System Mole in 1933

In 1917, Moore bought out Scott and renamed the business Moore Dry Dock in 1922. This centralized location was the beginning of a waterfront parcel of wetlands that would one day become known as Oakland Naval Supply Depot, also called, “The City Within The City“. Set on three-hundred and ninety acres of Oakland waterfront, terminating at the end of Adeline Street, where San Francisco Bay meets West Oakland, “The City Within The City” was at that time, the largest military installation in the entire world, which had its own police force, fire department, banks, stores, and baseball teams.

Moore Dry Dock Company – 1940

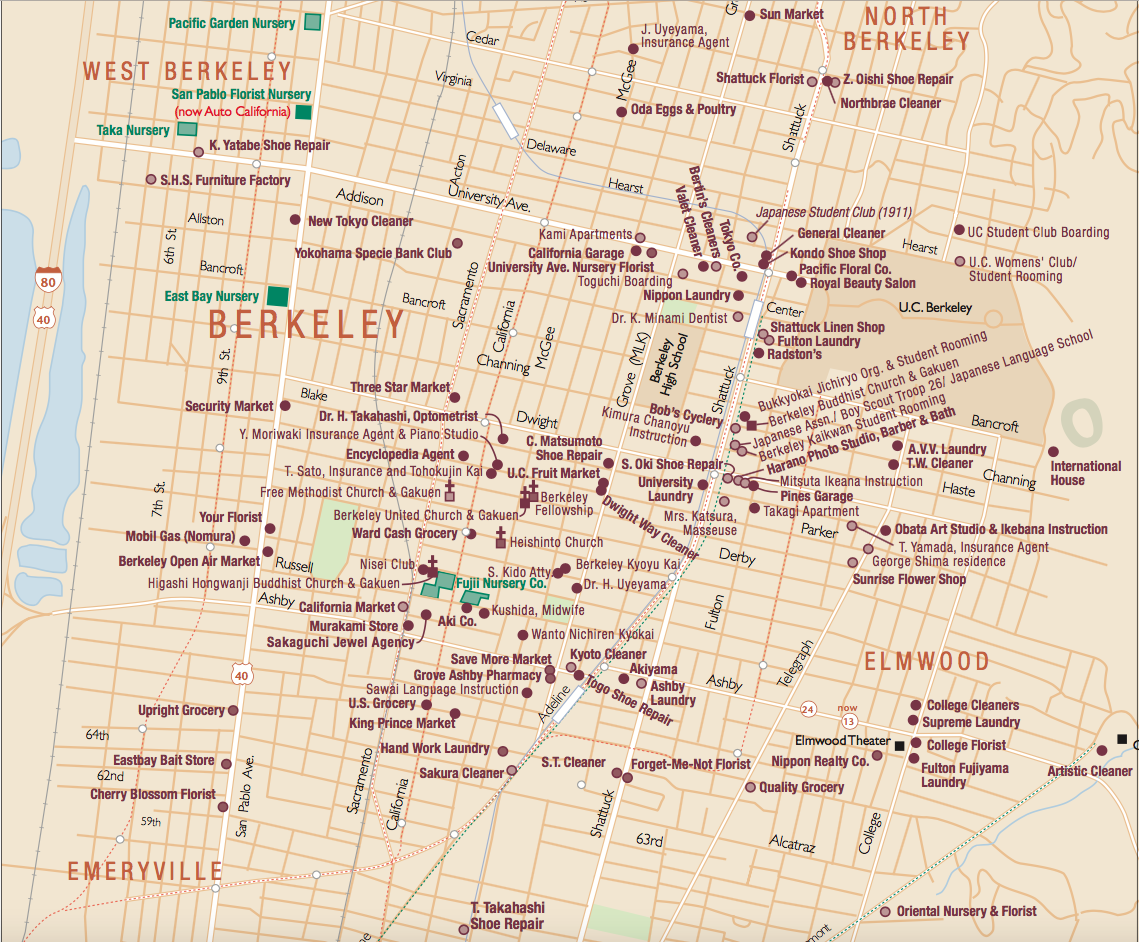

Today, “The City Within The City”, is known as Middle Harbor Shoreline Park, an off-the-beaten-path spot where families enjoy picnics, look at the Bay, or enjoy an outdoor concert. Less than four mile from “The City Within The City” was Oakland’s Japantown. Oakland had one of the largest Japanese populations in the United States, along with Los Angeles, San Jose, Sacramento, Berkeley and San Francisco. The Japanese community on the edge of Oakland’s Chinatown, has existed in this waterfront location since the 1880’s, which was mixed with African Americans, Italians, Eastern Europeans, Greeks, and Portuguese, that made up this Downtown Oakland neighbor, just North of Jack London Square.

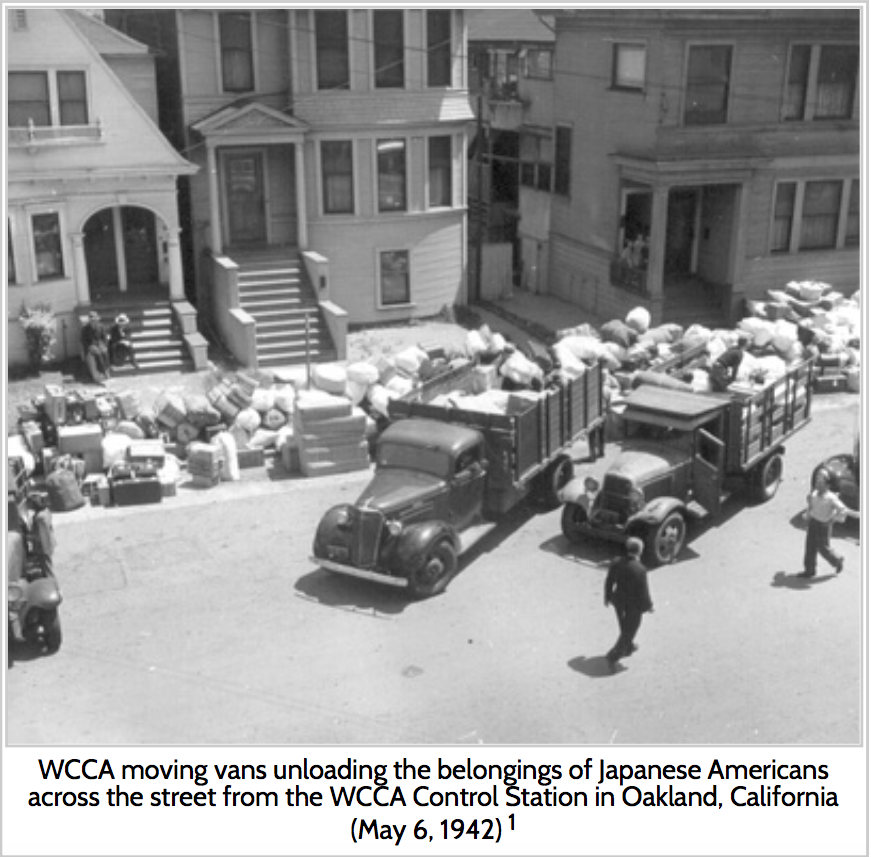

When this Dorothea Lange photograph is seen for the first time, of Tatsuro Masuda’s ‘commissioned sign’ stating “I AM AN AMERICAN”, unfurled and hung the day after Pearl Harbor was attacked by Imperial Japan, and placed in front of his storefront “The Wanto Co.”, — the reality of such a bold statement gives one a true sense between the dichotomy of being of Japanese American descent at the beginning of World War II, and how quickly the environment that you live in can change overnight. Between Oakland and Berkeley alone, more than 3,100 Japanese Americans were incarcerated, and close to 200 businesses were closed overnight. The Wanto Co, was located on 8th and Franklin streets in heart of Downtown Oakland, as were many Japanese businesses that were in close proximity of “The City Within The City“.

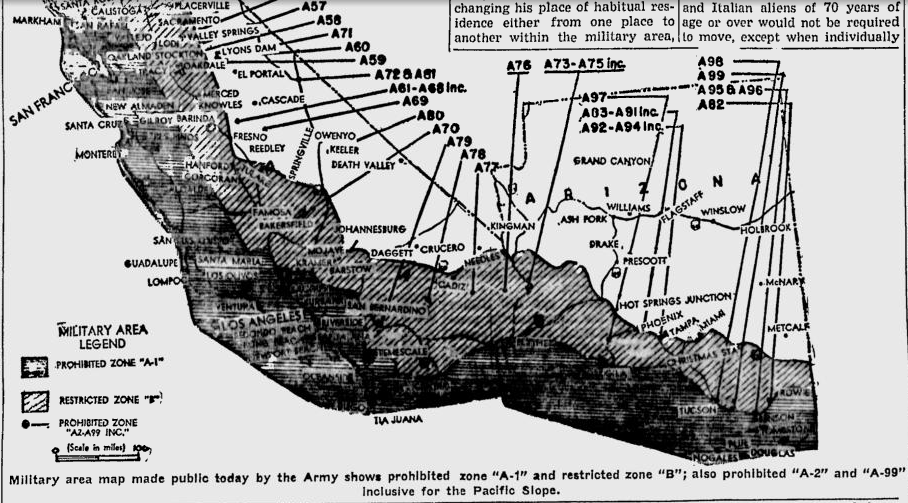

The Wartime Civil Control Administration Control Station, located at 530 Eighteenth Street, was one of 97 Wartime Civil Control Administration Control Stations in California. The Control Center located at 1117 Oak Street is now the Alameda County Law Library, and the one located at 530 Eighteenth Street is the Oakland School For the Arts. The expulsion of Japanese Americans that lived on the coastline of California, especially those that lived near military installations, was a rapid, expedient removal process, with little or no time to sell one’s property.

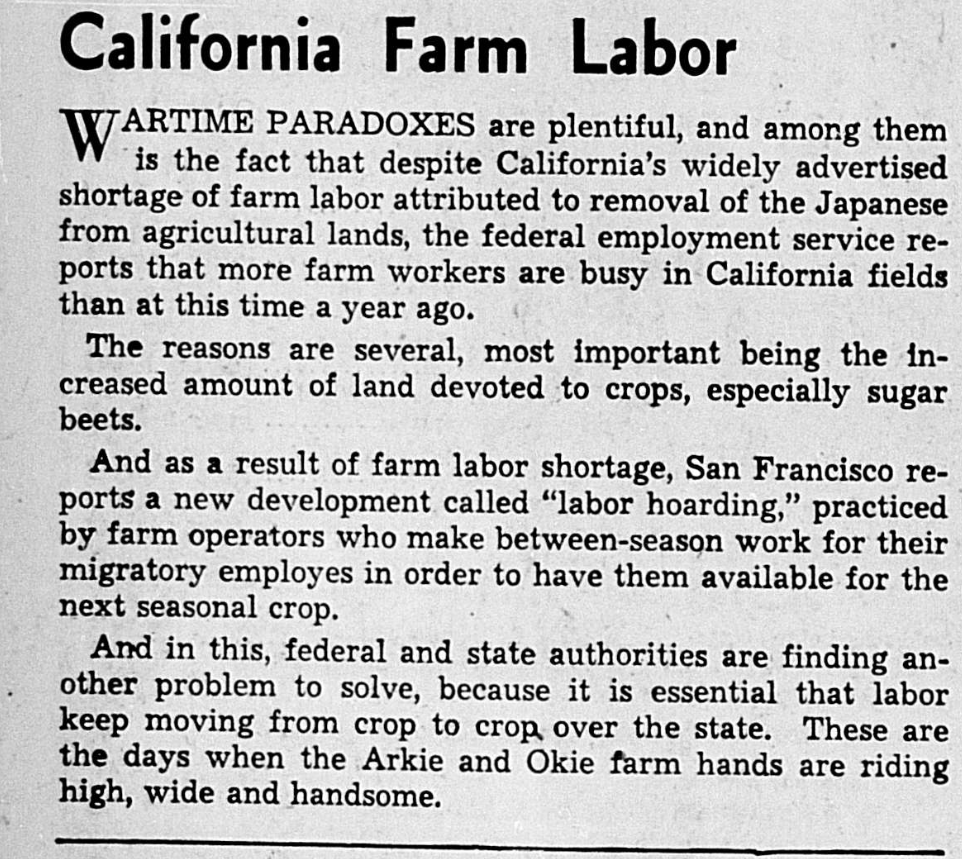

A restructuring of racial and pseudo-racial groups took place in the Bay Area, as well as a very large influx of Dust Bowl migrants making their way to the shipyards of the West Coast in search of a new way of life and gainful, steady employment. Neighborhoods that had once contained an accepted racial mixture of people soon became overtly segregated; not only by race, but also by socioeconomic class. The war effort brought more than just employment for everyone involved. It also brought along with it, a new social structure which uprooted long standing communities along the coast of California. One group of Americans entering the West for the first time were called “Dust Bowl Refugees“, while another group of Americans exiting the coast after living there for decades were called “Enemy Aliens“. Those that were not considered belonging in either group were placed in a precarious situation, figuring out how they would fit into this newly created wartime social structure.

The African American communities of the San Francisco Bay Area were caught in the middle between the incarceration of Japanese American families that they had lived in peace with for decades — and these recent arrivals; America’s newcomers to the West. They were trekking to a place that was settled long before their arrival, bringing with them a ‘Manifest Destiny’ attitude in tow. These new arrivals, who when presented with any opportunity to displace native Californians, would have replaced California born African Americans in a heartbeat, based on their antiquated Great Plains ideals and Southern values that they brought with them. To these Great Plains transplants, racial superiority meant everything, and was based solely on one’s skin color as an “all-or-nothing” proposition. During this period in history, their middle America experience with West Coast African Americans was based on the ‘outdated standard’ of living that had once prevailed in the United States.

A large number of Japanese owned stores, markets and businesses that served the African American community during the 1940’s segregated period in the West, were shuttered, never to reopen. This also created problems for Oakland and Berkeley’s local residents, who relied on these Japanese owned businesses for their shopping needs, in the West Coast segregated society that is rarely spoken of.

Emeryville to West Oakland Japanese American Owned Businesses – 1940

Berkeley to Emeryville Japanese American Owned Businesses – 1940

The tension created by this forced wartime migration of racially opposed groups, relocating to a centralized area that was known for its racial neutrality for the most part — began to show a marked change in daily life. These never before seen confrontations weren’t simply caused by an increase of a racially dichotomous population. Social gains that had been made by the African American communities in the Bay Area since the 1800’s began to rapidly dissolve, based solely on incoming xenophobic attitudes nurtured by newcomers unfamiliar with the ways of urban environment in America. In truth, the Civil Rights movement began before America’s involvement in World War II with the original March on Washington Movement, which prompted President Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 8802, testing this new anti-discrimination policy to its limits during World War II.

The main factor for a steady uptick and acceleration of racism, was primarily driven by the economic migration patterns of African Americans from the North and South, and similar migration patterns of the “Okies” and “Arkies” from the plains states to the West Coast. From the the very beginning of World War II, vast financial opportunities presented themselves for those who needed and wanted to work in the war industrial complex, which offered every man and woman three shift around the clock, which immediately began after December 7, 1941. This quick, and poorly planned hastening of manpower to fuel the war industry was a phenomenal undertaking, which made no room for the analysis of required housing needs of these wartime migrants, or social inclusion for those that showed up to support the war effort. Racism increased exponentially with this rapid migration of millions, and bigotry and prejudice was also a byproduct of a need for mass production to occur, as a rapid response to rebuild the destroyed American naval power.

San Pedro News Pilot — September 26, 1942

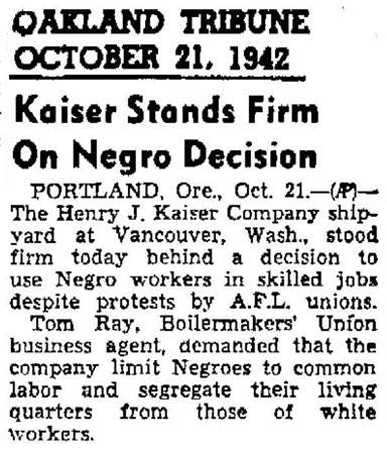

The war had also caused massive labor shortages in other industries, while this new, incoming multi-ethnic labor force threatened the long standing tradition of “white-only” shipyard metal trades workers — and “white-only” metal trades union membership.

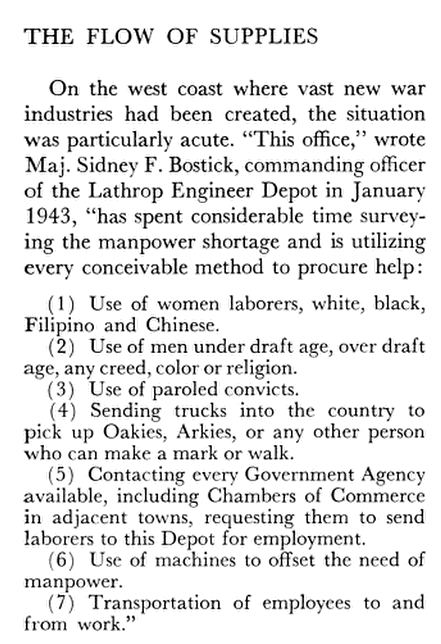

The Corps of Engineers – Troops and Equipment, Volume 6, page 541

San Pedro News Pilot, June 26, 1942

San Pedro News Pilot, November 10, 1943

Between 1940 t0 1944, the African American population on the West Coast increased by 113%!

In the locations of Portland-Vancouver and the San Francisco Bay Area, the African American population increased by 437% and 227%, respectively, thereby shrinking the already limited and segregated areas that African Americans had lived in for decades on the West Coast. Vanport, Oregon and Richmond, California were once military industrial boom towns during World War II, where Kaiser ship yards dominated the war time employment needs of the nation, and grew in population faster than housing accommodations for this new working class could be provided. Trailers and rode side shanties were not an uncommon sight to see along the roadways and empty lots in California wartime boom towns.

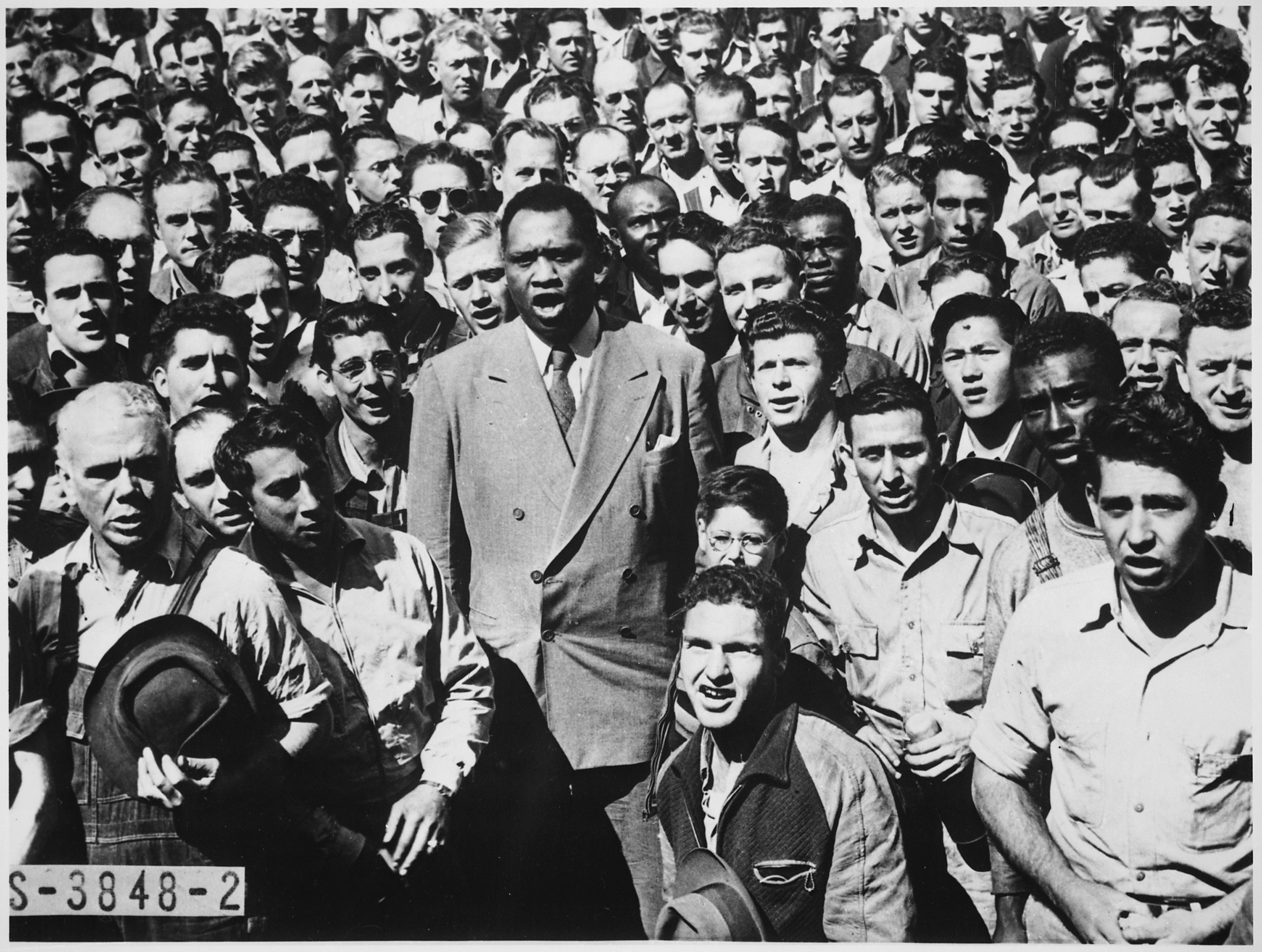

The War Manpower Commission was set up in 1942 to ensure a steady flow of able-bodied workers to meet the needs of the Dept. of War, the War Production Board, and the Labor Production Division of the War Production Board. At the same time, maintaining enough available draftees for the war in Europe, Africa and the Pacific, and workers for agriculture labor, and clerical workers for the United States Civil Service Commission was also a wartime imperative. The often seen images and photographs of World War II, gives one the impression that there was overall unified solidarity among the races, that played on the average American’s psyche, fostering a particularly strong sense of stoicism and reverence when it came to race relations within the work place. The undercurrent of those race relations were somewhat different.

Oakland Tribune – Paul Robeson singing the “Star Spangled Banner”, Moore Dry Dock, September 21, 1942. (Oakland Tribune Collection – Gift of ANG Newspapers) Jazz singer Lena Horne, christened liberty ship, SS George Washington, at Kaiser Shipyard, May 7, 1943 (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

Jazz singer Lena Horne, christened liberty ship, SS George Washington, at Kaiser Shipyard, May 7, 1943 (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

The Fair Employment Practice Committee, created in 1941 to execute Executive Order 8802, banned discriminatory employment practices by Federal agencies, and employers who contracted out work for the Federal government, and this included all unions and companies connected and engaged in wartime-related works. The executive order also established the Fair Employment Practices Commission to enforce this new policy.”. The Federal Government ability to end racial discrimination in the workplace was an uphill battle. The overall effect sometimes led to violence, as it did in Mobile,Alabama at the Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company, when 4,000 angry white employees attacked every African American connected with the shipyard they could find, after 12 African Americans were promoted to equal positions as their white counterparts.

When the A-26 Boilermakers’ donned their uniforms for the first time in the summer of 1942, and scheduled games against their opponents, there was little doubt that the objective was more than baseball.

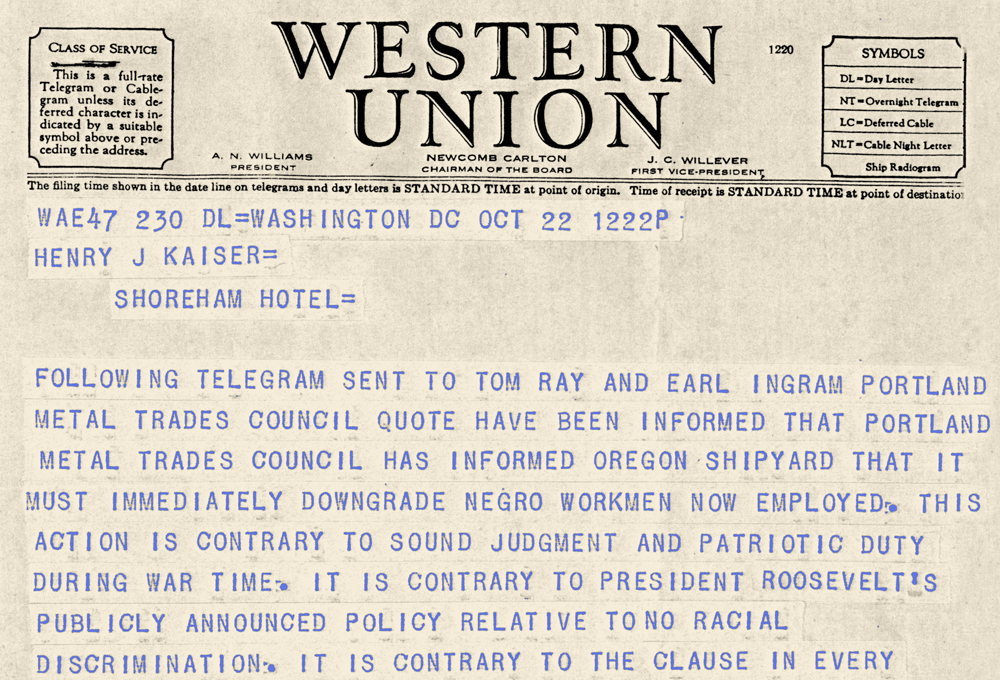

Western Union Telegram, from John. P. Frey to Henry Kaiser concerning demotions of African American shipyard worker- October 22, 1942

Western Union Telegram, from John. P. Frey to Henry Kaiser concerning demotions of African American shipyard worker- October 22, 1942

San Bernardino Sun – October 22, 1942

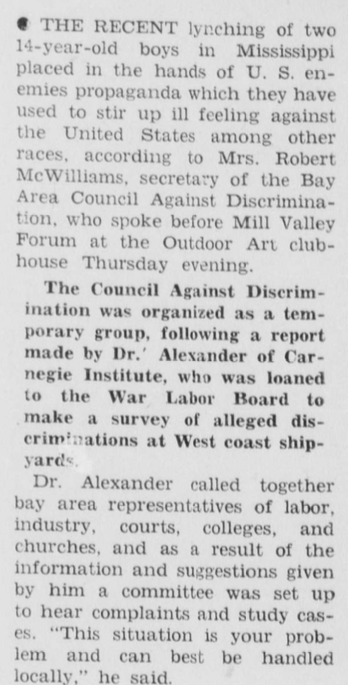

Mill Valley Record – December 15, 1942

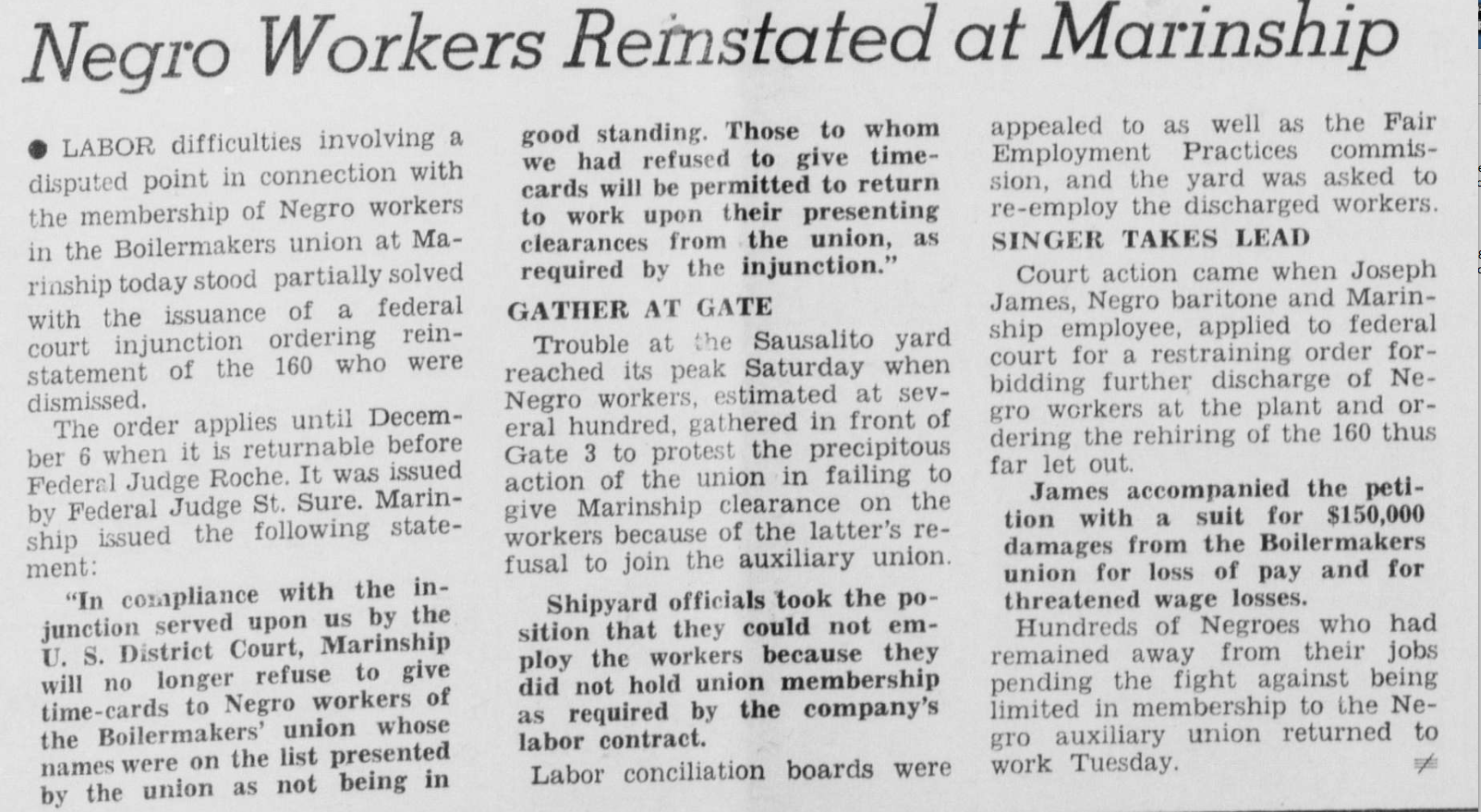

Organized Labor – August 21, 943.

San Pedro News Pilot – November 27, 1943

Negro Boilermaker Strike – Auxiliary Union Leaders meet before strike, November 20, 1943 –Marinship Corporation – Marin Shipyards. (UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library)

Negro Boilermaker Strike – Auxiliary Union Leader speaks to striking workers, November 20, 1943 –Marinship Corporation – Marin Shipyards. (UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library)

Negro Boilermaker Strike, November 20, 1943 –Marinship Corporation – Marin Shipyards. (UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library)

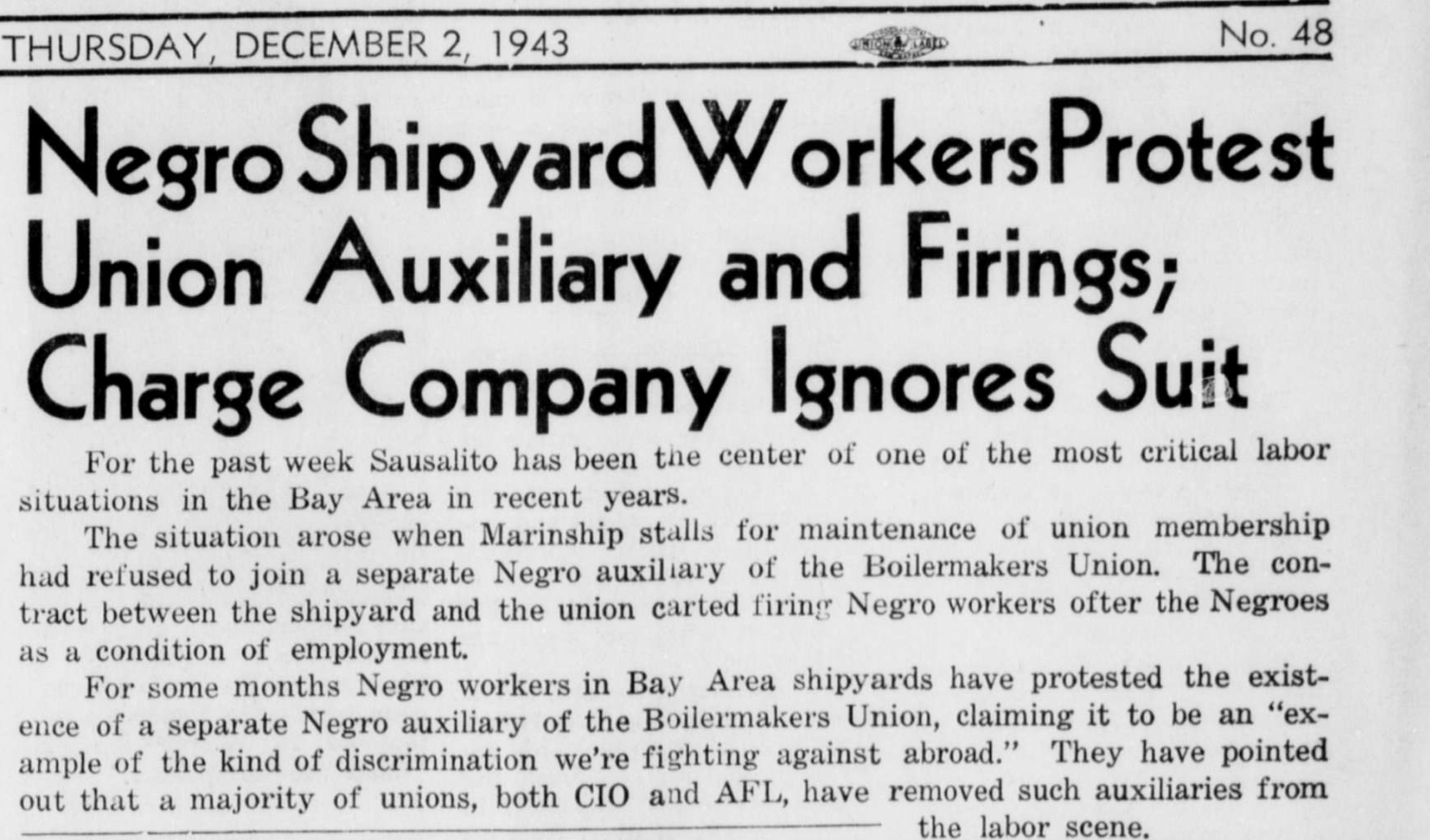

Mill Valley Record – December 2, 1943

Sausalito News – December 2, 1943

Mill Valley Record – February 24, 1944

Sausalito News – February 1, 1945

The West Coast was never immune to racial discrimination when it came to public life or the workplace, and this is true especially where employment was concerned.

The A-26 Boilermakers’ uniforms were a form of World War II “social media“, that kept the unrepresented African American shipyard workers in the public eye, using the sports page as a means to send political message. This ‘fashion as a form of protest’ strategy, or ‘dressing for dissent’, is a technique of political resistance or political activism, used in campaigns that address matters of much needed social reform. The A-26 Boilermakers’ uniforms made a undeniable statement of existence, — as the sport of baseball is a reflection of American culture in real time. What they chose to wear, what they named their team, what they called themselves, was a measured response to their daily lives that included “separate but equal”, — which was separate and very far from equal.

With their ever-present opponents at the “The City Within The City”, the Moore Dry Dock team, where white Boilermakers’ union counterparts lived and worked on a daily basis an acknowledgement of the A-26 Boilermakers’ existence was important. The A-26 Boilermakers’ were in some part responsible for initiation of the California Supreme Court case, James v. Marinship, in 1944. This landmark decision was an early test case for the ‘yet to become’ Supreme Court Judge Thurgood Marshall‘s skill set as a Civil Rights attorney for the N.A.A.C.P., which gave teeth to Brown v. The Board of Education.

The court battle between Marinship supported by the Local 6 versus Joseph James and the A-41 “auxiliary” union would last a year.

The International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Shipbuilders and Helpers of America were uncooperative when it came to the needs of the War Manpower Commission, and refused to comply with with Executive Order 8802, continuing the practice of segregation in the workplace under the auspices that these unions, and their locals, were “closed shop” white-only unions Even though “white-only” unions operated outside of compliance with the needs of the nation to end World War II quickly, segregation persevered and ignored Executive Order 8802 in its entirety. African Americans involved in the war effort’s ship building projects were required to make their own “auxiliary” unions and union locals — designated by an “A“. This action was only feasible with the permission of their ‘parent’ locals, where white union members and leaders made all the decisions for the disenfranchised African Americans shipyard workers.

A-26 were Moore Dry Dock workers in Oakland, A-36 were Kaiser Shipyards workers in Richmond, and A-33 and A-41 were Shipfitters in the Marinship Corporation in Sausalito. These “auxiliary” unions were controlled by their ‘parent’ locals, Local 9, Local 39, and Local 681 in Oakland, and Local 513 in Richmond. Nearly 20% of the workforce at Moore Dry Dock during World War II were African Americans, but they were also largely unrepresented in matters of labor and management. This particular baseball team, the A-26 Boilermakers, represented all African American wartime industry workers on the West Coast, and across the nation as well, in their struggle for union representation and equality under the law — as men and women who were classified as “union members” for all intents and purposes, but denied union representation and union benefits.

Before Rosa Parks refused to get up and relinquish her seat in the “colored section” to a white passenger, and move to the back of the bus, before John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised their black leather gloved clad fist at the 1968 Olympics and gave the Black Power salute, and long before Colin Kaepernick and Megan Rapinoe took a knee against police brutality — the A-26 Boilermakers,‘as a team‘, chose their moniker carefully, knowing full well that any articles written about them, ‘as a team‘, would draw attention to the plight of the African Americans who worked in the defense industry during World War II, and keep it before the public. Jim Crow was the follow up to Executive Order 8802. Today, it would be difficult to even imagine a person working in a union job, and doing so — required to pay full union dues, while having no voting power or representation, nowhere to air or arbitrate their grievances, required to accept reduced insurance coverage, — and were segregated from the main body of union members; but during World War II, segregation was not just limited to public spaces like diners, stores, theaters and buses.

Oakland Tribune -August 22, 1942

The A-26 Boilermakers were comprised of the following members:

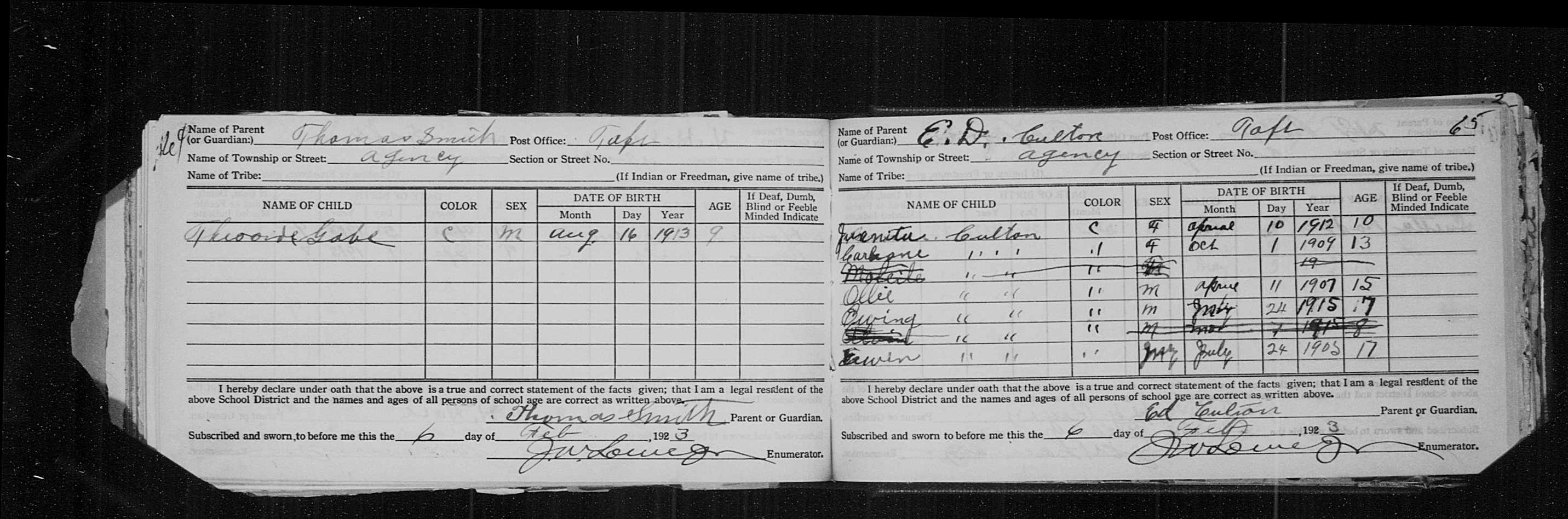

1) Theodore “Teddy” Gabe – Catcher

2) Claude Brown – First Base

3) Eddie Burke – Second Base

4) Les Saunders – Short Stop

5) Willie “Tat” Mays – Pitcher/Third Base

6) Al Plowers – Center Field

7) Rowland “Monk” Ewing – Second Base/Infield

8) Homer Holloway – Pitcher/Catcher/Outfield

9) Roy Edmonson – Right Field

10) Earl (“Minneweather”) Meneweather – Left Field

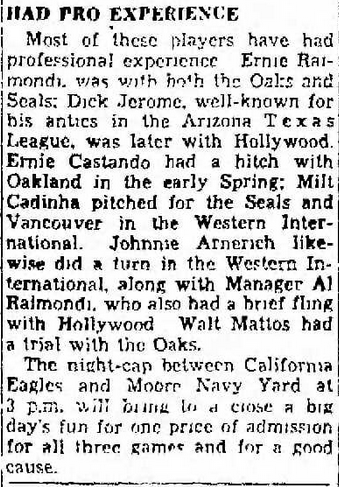

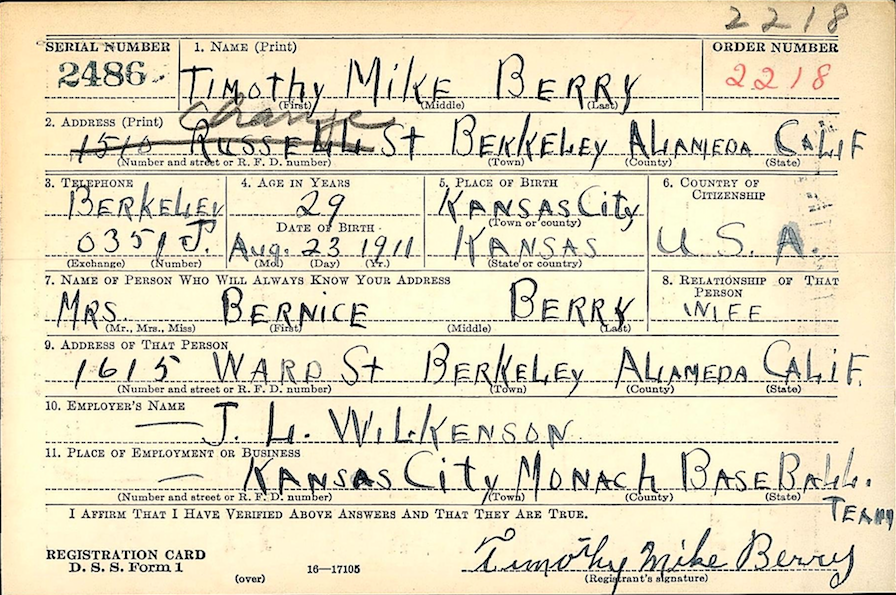

11) Timothy “Mike” “Showboat” Berry – Pitcher

12) “Wee Willie” Jones – Pitcher

Ernest (“Ernie”) R. Raimondi and Albert (“Al”) Raimondi were headliners for the Moore Dry Dock team line up. Both brothers had spent significant time in the Pacific Coast League, and were considered some of the best the league had to offer. These baseball series between the he Moore Dry Dock team and the A-26 Boilermakers were representative of how integrated baseball had developed over the last three decades in the San Francisco Bay Area, prior to World War II. These events would take place at Bayview Park or the Pacific Coast League’s Oaks Park in Emeryville.

Oakland Tribune -August 22, 1942

Home field for the A-26 Boilermakers was Bayview Park, opened to the public in 1910 in West Oakland, which eventually became Raimondi Park in 1947, in honor of Ernie Raimondi.

Herrick Iron Works can be seen in the background. They were a major supply source for steel for making Victory and Liberty ships in the Bay Area. ![Boilermakers A26 baseball team; [E.F. Joseph collection, Careth Reid; Sports]](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/boilermakers-a-26-team-pitcher-mike-show-boat-berry.jpg)

A-26 Boilermakers‘ Pitcher, Timothy “Mike” “Showboat” Berry, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

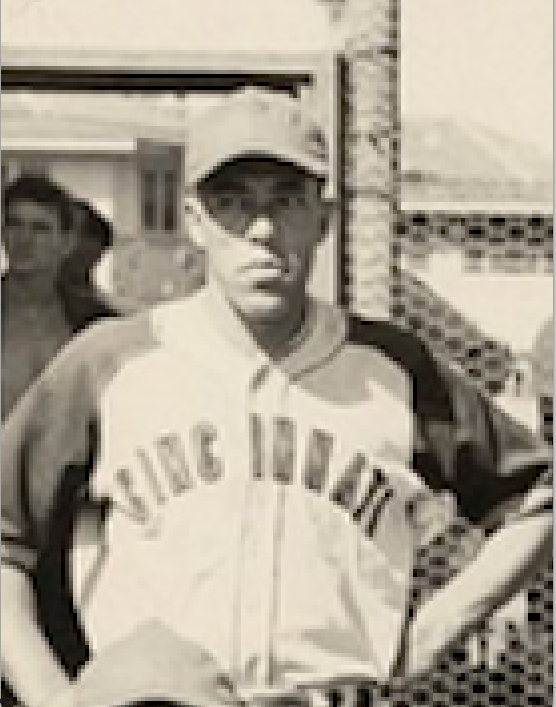

In his early years, Timothy “Mike” “Showboat” Berry, also known as “Cannonball” Berry, played for the Van Dyke Colored House of David. Eventually moving to the West, Berry was a individual who stayed mobile, even as a youth who was born in Kansas City. He played for the St. Louis Stars, Atlanta Black Crackers, California Eagles, Cincinnati Crescents, San Francisco Sea Lions, California Tigers, Kansas City Monarchs.

Timothy “Mike” “Showboat” Berry – WWII Draft Registration

.

California Eagles – Timothy “Mike” “Showboat” Berry -1940

Honolulu Star-Bulletin – Oct 5, 1946

Cincinnati Crescents 1946 (touring team)

Cincinnati Crescents – Timothy “Mike” “Show Boat” Berry – 1946![Boilermakers A26 baseball team; [E.F. Joseph collection, Careth Reid; Sports]](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/boilermakers-a-26-team-willie-tat-mays-bunting.jpg)

A-26 Boilermakers‘ Pitcher/Third Base, Willie “Tat” Mays, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

A-26 Boilermakers‘ Pitcher/Third Base, Willie “Tat” Mays , “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

The life of Willie “Tat” Mays is better explained in Gary Ashwill’s post, “Willie Mays, 1946 San Francisco Sea Lions“, at his blog Agate Type.![Boilermakers A26 baseball team; [E.F. Joseph collection, Careth Reid; Sports]](https://shadowballexpress.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/boilermakers-a-26-team-theodore-teddy-cabe-catching.jpg)

A-26 Boilermakers‘ Catcher, Theodore “Teddy” Gabe, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

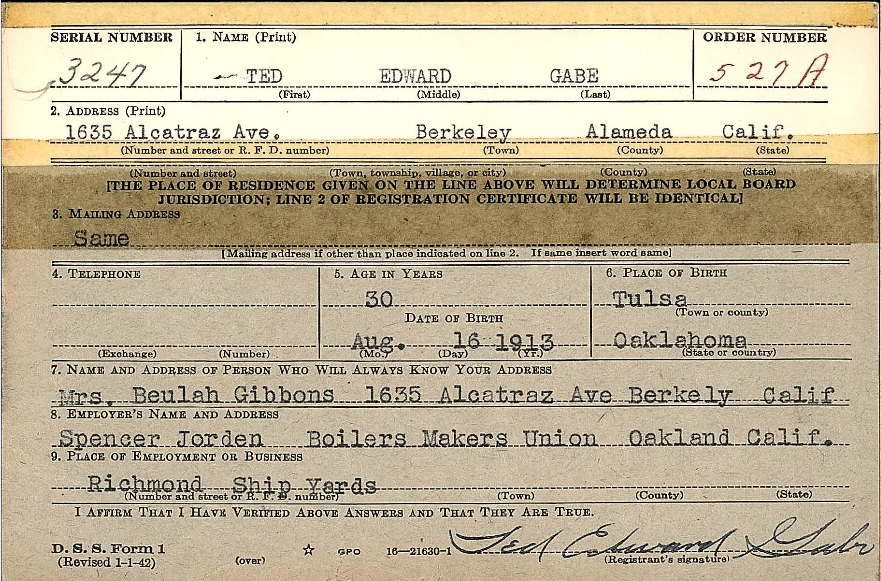

Theodore “Teddy” Gabe led a very interesting life. It began in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he grew up in a single parent home with his mother, Beulah, as a descendant of the Creek Freedmen of the Muscogee Creek, until he was removed by the state and sent to live in the Industrial Institute for the Deaf Blind and Orphans of the Colored Race, in Taft, Oklahoma. Gabe was actually from Oklahoma, but could never be considered an “Okie” under the rules of race and social class during World War II. His skin color dictated his social status.

Gabe was an educated man, who spent time at both the University of Washington and U.C. Berkeley, but in 1940, Gabe spent some time as a resident at San Quentin as prisoner #64693. After his release, he went to work at the Kaiser shipyards.

Theodore “Teddy” Edward Gabe – WWII Draft Registration

After the war ended, Gabe went on to play with the Oakland Larks and San Diego Tigers. He finished his degree at U.C Berkeley and went on to become a photographer apprentice with National Geographic.

A-26 Boilermakers‘ Pitcher, “Wee Willie” Jones, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

It has been said that “Wee Willie” Jones once played for the Zulu Cannibal Giants and the Van Dyke House of David, but the details are sketchy at best. Wee Willie Jones also went by the moniker “Sad Sam” Jones. Jones last stop was with the Oakland Larks, which ended his baseball career on an up note.

West Coast Baseball Association program –“Wee Willie” Jones -1946

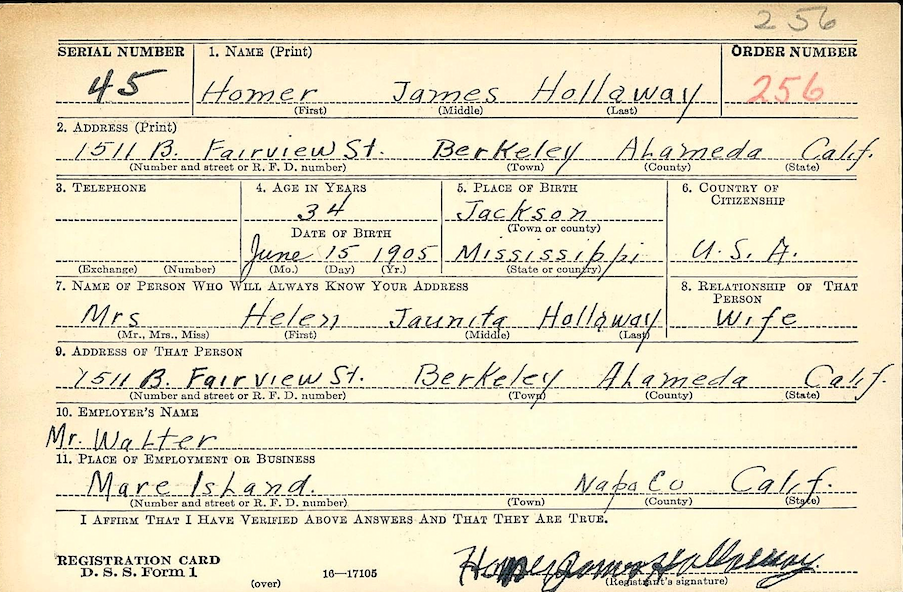

A-26 Boilermakers‘ Pitcher/Catcher/Outfield, Homer Holloway, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

Homer Holloway was once played ball for the St. Louis Blues. A transplant from Jackson, Mississippi, Holloway barnstormed in his early years with the Blues, and probably decided to stay in the West for reasons pertaining to steady employment. He played for the California Eagles, during their heyday as the Oakland Tribune Tournament Champions of 1940, where he was team mates with Mike “Show Boat” Berry and Claude Brown.

St. Louis Blues –Homer Holloway -1936

Oakland Tribune – August 27, 1940

Homer Holloway – WWII Draft Registration

Earl (“Minneweather”) Meneweather– Left Fielder for the A-26 Boilermakers, was a professional football player, spent two years playing halfback for the San Francisco Packers of the Pacific Coast Professional Football League who was a graduate of Humbolt State University. He was also a football and basketball star.

Earl (“Minneweather”) Meneweather was many things throughout his entire life.

A-26 Boilermakers’ Left Field, Earl (“Minneweather”) Meneweather, “Bayview” (Raimondi) Park. June, 18, 1942. (Office of War Information photographer Photo by E.F.Joseph)

Earl (“Minneweather”) Meneweather – Humbolt State University HOF

San Bernardino Sun – September 2, 1942

The A-26 Boilermakers were the forerunners in the passive resistance protest movements that would sweep America after Word War II, which became commonplace in the Civil Rights movements of the 1960’s. They let their skills at the shipyards and on the baseball field speak to what equality was supposed to represent when “All Men Are Created Equal” was the standard America was founded on.

“Heroes don’t always wear capes, …”

Sometimes they wear baseball uniforms.

Fantastic work, as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person